As one of the first food pantries in the country to move to a digital ordering and reservation system, Lutheran Social Services in Ohio is providing time-saving benefits to clients, while cutting costs.

LSS, which serves about 2,000 food-pantry clients a month in the Columbus area, started letting clients order food from home computers and/or mobile phones about a year and a half ago. Through software provided by Analytic Solutions in Boston, clients can place an order any time of day or night and schedule a time to pick it up. Being able to pick up a prepared bag at an appointed time has turned what has traditionally been a two- to three hour-long wait at the pantry into a more streamlined 20- to 30-minute process.

“The number-one benefit for our clients is convenience and respect for their time,” said Jennifer Fralic, director of pantries at LSS.

Clients shop with points (20 per family, plus about ten extra for each additional person) and get charged fewer points for healthier items. The software from Analytic Solutions, called SmartChoice, also lets LSS better manage its inventory on the backend. “We get a sense of what moves faster,” Fralic said. “It helps us to know how to spend our money.”

Clients only shop for non-perishable items online. Once at the pantry, they pick out fresh produce and bread (mostly available in unlimited quantities) and meat based on family size. “We can’t control the inventory on those items, so clients pick them out” in person, Fralic explained.

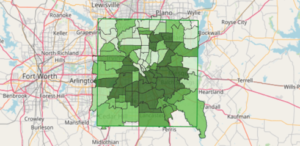

With more streamlined pickups, LSS has been able to dramatically pare down the amount of dedicated space it needs to do distributions. Before online ordering, LSS had five storefront locations that housed and distributed food. Now it has one brick-and-mortar distribution site that will also act as a central warehouse. Other distributions now occur through partnerships with two local community centers that each host two pop-up pantries a week.

Even with the increased costs of having to transport food from the central warehouse to the community centers, there are savings. For example, LSS is saving $6,000 a month in rent and utilities from just one of its storefront closings, Fralic said.

While taking advantage of existing community centers to distribute food is an attractive idea, Fralic emphasized that buy-in from potential partners is key. Initially, LSS was working with six community centers, but not all were receptive to the disruptions that can come with hosting a pop-up food pantry, such as the need to move around large pallets of food. “I cannot stress enough the importance of great partnerships with the host site,” Fralic said.

Of the wholesale changes that LSS made to its pantry distribution system, Fralic noted, “Online ordering was not the struggle. It was finding the right partners.”

In fact, clients easily adapted to online ordering, disproving pushback LSS got from some quarters that food-insecure people do not have access to computers or know how to use them. “We know that other social services are done online, so why not food?” said Fralic. “It shows respect for the people you serve.” About 80% of clients order their food online, while the rest take advantage of a telephone help desk that is open daily.

By coincidence and unbeknownst to Fralic, Lutheran Social Services of Nevada also offers online ordering at its food pantry, which it calls DigiMart. LSS of Nevada says DigiMart became the first digital food pantry in the country when it was introduced in 2016.

Connect with Us: