Food banks have long said that they’re only as good as their pantry networks, and lately, they’ve been backing up that sentiment with intention.

Fueled partly by Covid-era support, food banks have been growing the capacity of their pantries through a wide range of grant-making activities. Now, many are at a stage of formalizing those grant programs as they seek to make capacity-building a standard part of their operations.

High demand for food during the pandemic underscored the need for robust pantry networks, hitting home the reality that pantries could become bottlenecks if they were not equipped to handle growing amounts of food.

“We knew if we increased our capacity as an organization, we needed to make sure our partners also had the capacity to serve more people, because we can’t do it all ourselves,” said Trisha Cunningham, President and CEO of North Texas Food Bank. “We knew that investing in our partners was going to be critical.”

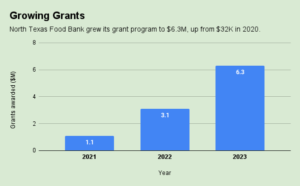

North Texas Food Bank, which distributes 90% of its food through its agency network, awarded $6.3 million in network grants in 2023, up from $1.1 million in 2021, and $32,000 the year before. It has also diversified the types of grants it offers, moving from straight capacity-building to include more specialized offerings, such as its Service Insights grants to equip pantries with laptops and iPads so they can take advantage of Feeding America’s client intake system, and its Leadership Development scholarships to help pantry leaders take part in a management certification program.

North Texas Food Bank, which distributes 90% of its food through its agency network, awarded $6.3 million in network grants in 2023, up from $1.1 million in 2021, and $32,000 the year before. It has also diversified the types of grants it offers, moving from straight capacity-building to include more specialized offerings, such as its Service Insights grants to equip pantries with laptops and iPads so they can take advantage of Feeding America’s client intake system, and its Leadership Development scholarships to help pantry leaders take part in a management certification program.

Increasingly, food banks are aligning their grant giving to match their strategic goals. At Maryland Food Bank, for example, the three types of grants it offers match up with the three aims of its mission statement, which is to feed people, strengthen communities, and end hunger for more Marylanders.

Its Food First Capacity grants go toward feeding people. “They’re quick, they’re easy, and they’re not very big,” said Meg Kimmel, Chief Operating Officer at Maryland Food Bank. Of the $2 million in total that the food bank granted in 2023, about $750,000 went toward these capacity building grants, which are designed to support items like refrigeration, shelving, vehicles, and maintenance.

The food bank recently lowered the maximum amount awarded for those grants from $12,000 to $7,000 because it found pantries were mostly requesting lower amounts. “We figured if we lowered it, then we could spread it out further,” Kimmel said, adding, “We want to make it as easy as possible for them to come to the food bank and get that funding, so they can keep doing more.”

The food bank’s Hunger Hotspot grants speak to the “strengthening communities” goal of its mission statement. Using the Maryland Hunger Map, the food bank’s six regional directors identify areas that are under-resourced and would benefit from funding to stand up new distribution partners or expand existing ones. Each regional director gets $100,000 to deploy in this directed way. “They’re intended to be a very powerful tool for our regional program directors to change the reality in certain communities,” Kimmel said.

Most recently, the food bank has introduced its Neighbor Impact grants, which align with its strategic goal to end hunger. The food bank awarded six of these grants (out of an applicant pool of 41) in chunks of $100,000 for year one, and $75,000 for year two. Intended for network partners, as well as outside organizations, these grants go to support innovative systems-level change that gets at the root causes of hunger, Kimmel said.

One such grant was made to the Black Church Food Security Network, which will fund its ability to use church lands for community gardens, as well as an apprentice who will join the food bank’s sourcing team to learn about food distribution. “We’re using this apprenticeship to directly support the transfer of information and knowledge over to this organization and ultimately communities,” Kimmel said. Another grantee will provide automotive repair training in a struggling neighborhood, making available a type of instruction the food bank does not offer in its workforce development program.

North Texas Food Bank has similarly added Hope for Tomorrow grants, which address the root causes of hunger, aligning with its strategic plan of providing Food for Today, Hope for Tomorrow. One of these grants enabled a partner to hire a coordinator for its education program teaching job readiness, English as a second language, and life skills. “It’s not just feeding the line and building that capacity, but how can we build up programs for wraparound services for our partners?” said Anne Readhimer, Vice President of Community Impact.

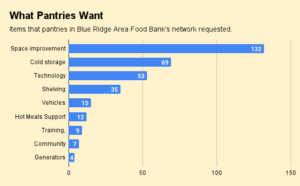

Blue Ridge Area Food Bank also awards grants in accordance with its strategic priorities of eliminating disparities in access to food, improving health, and supporting financial household stability, said Tyler Herman, Director of Partner Engagement. It balances those priorities against what its partner engagement managers know about the saturation of services in a region and the ability of a partner to carry out the goals they’ve outlined. “It’s a dance of weighing these different elements to figure out which sites make the most sense,” Herman said.

Blue Ridge Area Food Bank also awards grants in accordance with its strategic priorities of eliminating disparities in access to food, improving health, and supporting financial household stability, said Tyler Herman, Director of Partner Engagement. It balances those priorities against what its partner engagement managers know about the saturation of services in a region and the ability of a partner to carry out the goals they’ve outlined. “It’s a dance of weighing these different elements to figure out which sites make the most sense,” Herman said.

In 2023, the food bank awarded grants to 80% of applicants, though most did not receive all the funding they asked for, with only 26% of all funding requests being met. The food bank values a diversity of requests, Herman said, noting, “We believe in the potential impact of all our partners, whether they’re serving 15 people or 2,000 a month.” He cited a partner that moved to distributing 1.3 million pounds of food under new leadership, after being stagnant for years at 300,000 pounds. “You don’t know when you’re going to harness impact,” he noted.

In 2024, the food bank will be introducing a new vetting tool intended to help it better center equity in its funding decisions. The tool gives extra weight, for example, to pantries that serve under-resourced areas and communities of color. It also prioritizes pantries that incorporate guest feedback into most decision-making.

With Covid-era funding winding down, food banks are entering into a period of assessment about how they will sustain their capacity-building grants going forward. Maryland Food Bank’s capacity-building program is still in a pilot stage, for example, so its Strategy Group will be evaluating the future of the program, including the dollar amounts to be granted and the resources needed to support the program, Kimmel said.

After awarding $2.1 million in 2021 and $1.4 million in 2022, when Covid-era funds were flowing, Blue Ridge Area Food Bank has leveled out at about $400,000 to $500,000 annually in grants, which it’s likely to sustain going forward, Herman said.

North Texas Food Bank expects existing funding for its grant program will likely run out next year. In anticipation, it is helping some of its partners go through training and development to become proficient in seeking out other grants in the community. The future of the capacity-building program will no doubt be part of the food bank’s next round of strategic planning, and it may end up as a smaller, but more stable program. Noted Cunningham, “We’ve seen a lot of value in investing in our partners.” – Chris Costanzo

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News

This article was made possible by the readers who support Food Bank News, a national, editorially independent, nonprofit media organization. Food Bank News is not funded by any government agencies, nor is it part of a larger association or corporation. Your support helps ensure our continued solutions-oriented coverage of best practices in hunger relief. Thank you!

Connect with Us: