While giving clients the opportunity to choose their own food is widely considered a food-pantry best practice, taking the step to add more choice can feel overwhelming, especially when current operations seem to be working just fine.

McDonald Mission Center, an agency of Second Harvest Food Bank of Northeast Tennessee, was among the skeptics when it became part of a recent cohort of 111 pantries that participated in a study to measure the impact of choice. “We were probably the biggest naysayers that it would work,” said Rick Wisecarver, who helps manage the center.

Now, McDonald Mission Center is a convert, having witnessed the benefits of choice within its own organization. Its experience dovetails with those of its fellow study participants, most of whom also described a range of benefits earned by moving to choice.

“Choice is a better way to run a pantry,” said Michael Reynolds, Senior Vice President at NORC, a social research organization at the University of Chicago, which helped run the study. Reynolds is a co-author of the study, along with Katie S. Martin, CEO of More Than Food Consulting, and others.

The study measured the impact of Feeding America’s Choice Capacity Institute, created through a multi-year grant from Morgan Stanley Foundation and aimed at expanding choice at pantries. Feeding America selected 28 food banks and some of their pantries to participate in the Institute, which included ten monthly virtual sessions in 2021 focused on creating a shared language around choice, defining four levels of choice, and offering strategies for increasing it.

The virtual sessions encouraged food banks to help their pantries move along a “choice continuum” ranging from no choice, to limited choice (choosing between 2 or more types of pre-packed items, with the option to decline or choose extra items), to modified choice (choosing from a menu of items that volunteers bag), to full choice, in which a pantry operates like a grocery store.

Before offering choice, pantries cited numerous potential barriers to supporting it, including not having enough volunteers and staff (32%), nor space (27%), nor time (22%), as well as the belief that it was more efficient to prepare bags in advance (29%). Reynolds said pantries also wondered whether volunteers and clients would embrace the change, and whether the change would be worth it.

Growing acceptance of drive-through pantries as a result of the pandemic also proved to be a barrier. (Food Bank News wrote about the post-pandemic staying power of drive-throughs here.) Some pantries in the study opted against moving to choice at all because they viewed drive-throughs as more efficient, as well as convenient for senior citizens who could remain in their cars.

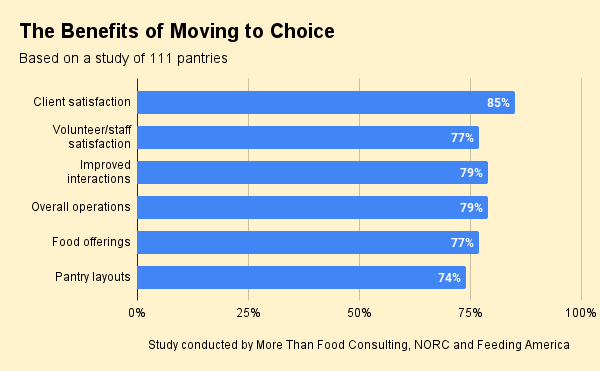

Despite these concerns, the study documented widespread positive outcomes among the responding pantries that increased choice. Pantries said clients were more satisfied (85%), as were volunteers and staff (77%), and interactions between the two improved (79%). “No matter the location of the pantry, the community, the size, the resources, the space, everybody could move to some form of choice,” Reynolds said.

In addition, operational flow improved. Pantries said overall operations improved (79%), along with food offerings (77%) and pantry layouts (74%). The operational improvements were not a surprise to Reynolds. “By not wasting so much on food that nobody wants, we can double down and spend resources more efficiently,” he said.

The conversion of McDonald Mission Center toward choice began with learning more about its benefits. “After listening to some of the conversations that we were involved in, we got to understanding,” Wisecarver said. “If we go to the grocery store, we pick what we want. They don’t put it in our bag for us or tell us what we’re going to purchase.”

After surveying its clients, McDonald Mission Center realized a majority would rather choose their own food. So it placed items on tables for clients to select. “When we changed … we changed,” Wisecarver said. It took a bit of getting used to, but the impact was clear. Volunteers are happier and clients who come inside to shop appreciate the conversation. “We have found too that it reduces our workload,” Wisecarver added. “It doesn’t take as many volunteers to get it all set up.” Instead, those much-needed volunteers can shift to other roles, such as assisting clients as they shop.

The move also led to some surprises. Some items that McDonald Mission Center assumed everyone wanted, such as macaroni and cheese, peanut butter, and rice, for example, weren’t actually that popular. Pop Tarts and canned beef stew, on the other hand, were high on shopping lists. To meet demand, McDonald Mission Center has expanded the list of providers from which it sources food.

Training, especially for volunteers, is critical to overcoming hesitation, said Reynolds of NORC. “If you have a good training around why we’re doing this and what’s important and what we think we’ll gain, you stand to have a lot more buy-in and less resistance.” At the same time, once pantries saw how choice improved operations, “it really didn’t take a lot more work to convince people that moving to choice just made it easier in some ways.” Better interactions between volunteers and clients proved equally convincing. “It just seems to introduce much more of this idea that we’re all in this together,” Reynolds said. “It just sells the program.”

As the Choice Capacity Institute enters its third and final year, the focus will shift to creating standardized tools to help more pantries add choice. One such example is the Choice Visual Library on Feeding America’s Learning Hub, where food banks and pantries show how they’ve increased choice in their workspaces. The goal, Reynolds explained, is to develop a consistent way to think about adding choice, no matter who is conveying the message. — Amanda Jaffe

Amanda Jaffe is a writer and former attorney with a deep interest in organizations and mechanisms that address food insecurity. Her online publication, Age of Enlightenment, is available on Substack, and her essays and articles may be found at www.amandajaffewrites.com.

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News

This article was made possible by the readers who support Food Bank News, a national, editorially independent, nonprofit media organization. Food Bank News is not funded by any government agencies, nor is it part of a larger association or corporation. Your support helps ensure our continued solutions-oriented coverage of best practices in hunger relief. Thank you!

Connect with Us: