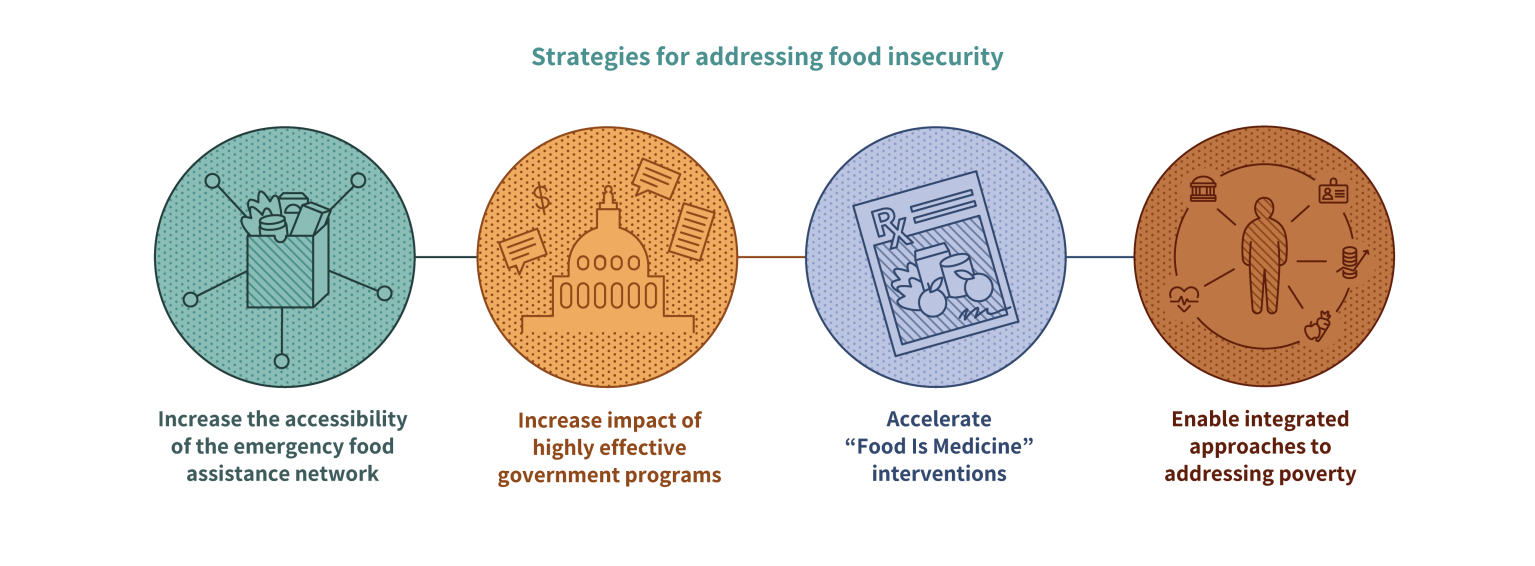

In a recent report about food insecurity in its region, Capital Area Food Bank took the additional bold step of identifying four broad fixes to food insecurity, putting forth a viable blueprint for other food banks in the country.

As in much of the nation, food insecurity in the capital region has remained stubbornly high, with 32% of the population experiencing it at some point between May 2022 and April 2023, on par with 33% the year prior. Also in keeping with national trends, Capital Area found race to be a factor, with 44% of food-insecure individuals being Black, 27% Hispanic, and 18% white.

Perhaps the most forward-thinking of Capital Area’s four recommendations is an emphasis on Food as Medicine interventions. Its report underscores the need, noting that food-insecure people in its area are more than twice as likely to suffer from chronic disease as those who are food-secure.

In Capital Area’s view, the sweet spot for food banks in the Food as Medicine field is medically tailored groceries, with food banks providing healthy food over long periods of time to people fighting diet-related disease. “That’s where I think food banks have a gigantic role to play,” said Radha Muthiah, President and CEO of Capital Area Food Bank. “We cover every inch of this country and we are in the business of providing good, nutritious food to people.”

Food banks also need to be contributing to the research showing positive outcomes in Food as Medicine. To this end, Capital Area is working with Children’s National Hospital to track the medical outcomes of 200 patients receiving medically tailored groceries weekly for a year.

Like a growing number of food banks, Capital Area is also working on the ground, running an on-site food pharmacy at Children’s National to provide healthy groceries to the families of food-insecure children with diabetes.

To ensure ongoing impact, advocacy around Food as Medicine is also important, which has led Capital Area to form a wide range of non-traditional partnerships, such as with the Tufts Friedman School of Nutrition as well as insurance payers, healthcare providers and hospital systems. “We can all do the best that we can, but we can’t function in our own silos. So we have to come together and be part of this larger mosaic,” Muthiah said.

One end goal of the advocacy is to make it possible through state and federal regulation for Food as Medicine programming to be covered by insurers as a reimbursable benefit. “I absolutely see a day when we will be reimbursed for healthy food, either directly or indirectly,” Muthiah said. “And I do not see this ten years from now. I personally see this in three to four years from now.”

Another strategy for addressing food insecurity is the more nuts and bolts matter of increasing access to the hunger relief network. Too often, food insecure people are not aware of the resources available to them. Capital Area’s 2021 report found that 59% of its clients only knew of one location where they could access free food.

The steps to be taken here are basic, like pantries offering hours of operation that are longer, or at least better aligned with the working schedules of their clients. Alternative service models like home deliveries are also key. Getting information out about available services is also important, and Capital Area sees local social media outlets, such as neighborhood Facebook pages, as useful in that regard.

As Capital Area continues to evolve its pantry network, it is also seeking to add partners in the neighborhoods where its clients live, helping to ensure that the languages spoken and foods served are more relevant. Its goal is to have 40% of the food it distributes be culturally appropriate, a target it is measuring every day, Muthiah said.

Its third strategy to fix food insecurity is to pair food with other services for low-income people, such as healthcare screenings or workforce development classes. Some food banks are already pursuing this type of strategy in a big way. Feeding Tampa Bay, for example, is building an Opportunity Hub, in which 50% of the hub’s non-warehouse space will be dedicated to a variety of community partners, as well as a grocery-store-style pantry. Similarly, Greater Cleveland Food Bank is set to open a Community Resource Center this fall, which will house a grocery-store-style pantry, as well as roughly 10 nonprofit partners in areas such as healthcare, financial literacy and housing.

Capital Area’s final recommendation is to strengthen highly effective government programs like SNAP, income-based tax credits, and TEFAP. Its report points out that SNAP provides nine meals for every one provided by the food banking network. – Chris Costanzo

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News

This article was made possible by the readers who support Food Bank News, a national, editorially independent, nonprofit media organization. Food Bank News is not funded by any government agencies, nor is it part of a larger association or corporation. Your support helps ensure our continued solutions-oriented coverage of best practices in hunger relief. Thank you!

Connect with Us: