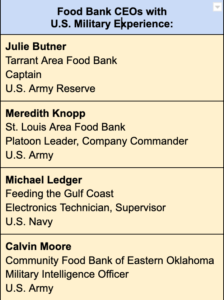

It’s fair to say that most food bank CEOs reach their positions after working at other food banks or non-profit social service organizations. But some CEOs have taken other, more circuitous routes to the top spot. A handful have spent years in the U.S. military (see chart). Other unusual pathways include the aerospace industry, university athletics and finance. Here’s a look at four distinct career paths and how they are helping to shape the CEO spot.

Nathan Springer

Care and Share Food Bank, Colo.

Former U.S. Military Commander

Nathan Springer spent 24 years in the U.S. Army before becoming CEO of Care and Share Food Bank in Colorado Springs, Colo., just over a year ago. His most recent Army post was presiding over Fort Carson in Colorado Springs as Garrison Commander, which is somewhat like being the mayor of a large city. Most of his Army career, however, was spent as a light calvary officer, a position that involved jumping out of airplanes and helicopters and leading soldiers on long-range reconnaissance missions in areas all over the world, including Afghanistan and Iraq. Springer is the Captain Springer who appears in the book, The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor, by Jake Tapper (now of CNN), which was published in 2012 and made into a movie in 2020.

Retiring from the military to go into food banking was not part of Springer’s plan, but something he “fell backwards into,” he said. A family vote had persuaded him to end his military career, and Springer was just days away from accepting one of three for-profit job offers when he found out about the Care & Share opening. “I really couldn’t have found a better fit,” he said.

In his travels through 44 nations throughout his Army career, Springer witnessed heartbreaking examples of hunger and food insecurity, especially on his Middle East and South Asia deployments. He also helped to manage family programs addressing food insecurity among the military while at Fort Carson. But his Army experience in logistics and management may hold the most directly relevant experience for food banking.

In his travels through 44 nations throughout his Army career, Springer witnessed heartbreaking examples of hunger and food insecurity, especially on his Middle East and South Asia deployments. He also helped to manage family programs addressing food insecurity among the military while at Fort Carson. But his Army experience in logistics and management may hold the most directly relevant experience for food banking.

Springer brought that experience to bear on Care and Share’s service area of 29 southern Colorado counties over 50,000 square miles. In one example of his influence, a new distribution center that was originally built to act as a spoke to the food bank’s main distribution center will now operate as a second hub, cutting down on transportation time and fuel, and adding much greater efficiency.

Springer has also moved to make Care and Share a flatter organization by creating an executive leadership team that makes decisions jointly. “The best organizations in the military that I was in were very flat and not hierarchical,” he noted. “You felt like you had very great latitude to do the right thing without having to ask.”

Fred Glass

Gleaners Food Bank of Indiana

Former Athletic Director at Indiana University

Fred Glass “loved every day” of his nearly 12 years as the Athletic Director at Indiana University, but confessed “it’s a tough job and I wanted to be doing something else.” After a brief detour back into private-practice law, Glass welcomed the CEO spot at Gleaners, fulfilling his desire to lead a more service-oriented life.

One of Glass’s first tasks at Gleaners was to define the food bank’s purpose, mission and values – an exercise he took very seriously at Indiana University, where he and his team crafted five priorities that guided almost every decision around hiring, firing, budgeting, and scheduling. At Gleaners, he wanted to signal the food bank’s focus on collaboration. So the previous mission, “to lead the fight against hunger,” was subtly changed to “be a leader in the fight against hunger.” Noted Glass, “I think that small change has been a big deal,” and welcomed by community partners.

A big believer in branding, Glass also created a label to help unify Gleaners, much as he had at the university. At Indiana, the brand, “24 Sports One Team” helped bring together the sprawling athletic department. At Gleaners, “One Gleaners” has worked to break down silos between different parts of the organization (more on that here).

Glass’s background as the only child of a father who owned a skid row bar has also shaped his approach to food banking. As a kid, Glass sat and talked to people who most would dismiss as beneath them. He also got to see early on that the power structure could be unfair, such as when the police might be persuaded to stop hassling patrons when given a fifth of whisky to leave. “It was a transformative thing for me because I got to know the clientele as people,” he said.

Kenneth Estelle

Feeding America Western Michigan

Former Aerospace Executive

Ken Estelle spent years in the aerospace industry before becoming CEO of Feeding America West Michigan 12 years ago. Among the business management techniques he brought to the food bank was Six Sigma, a data-driven approach that aims to drive out wasteful procedures and improve processes.

One of his first actions as CEO was to shut down the food bank and conduct training on a version of Six Sigma known as lean Six Sigma. That was followed by a dozen or so Kaizen events, which are short-term workshopping sessions directed at improving specific business processes. “I drove everybody crazy, but we did improve a lot of things,” Estelle said.

His business background, however, was not as useful in helping him understand the local social services scene, which he called “a complex network.” He noted, “I was way behind the eight ball in terms of figuring out how to navigate the social service network locally as an aerospace guy.”

Estelle found he was most impressed by the values of the people working in hunger relief. As a senior executive in the aerospace industry overseeing 3,000 people, he had a lot of conversations with mid-management leaders about how to get to the next career level. “At the food bank, people are all about the mission and how to help more people,” he said. “My only regret is that it took me 32 years to figure out what I really needed to do.”

Kristen Miale

Former CEO, Good Shepherd Food Bank, Maine

Former Finance Executive

On June 30 of this year, Kristen Miale moved on after 13 years from her position as the head of Good Shepherd Food Bank. But the story of her route to that spot is still worth telling.

As the financial advisor to a family-office investment firm in Maine, Miale had a front-row seat to the “incredible concentration of wealth and power that exists in this country,” she said. Meetings with other rich and influential people were easy to get, while at the same time, disasters like the subprime mortgage crisis exposed the lack of loyalty between so-called partners. “Everyone was out for themselves,” Miale said. “It was just awful.” She realized, “This whole system is so wrong. I just really felt, ‘I can’t do this anymore.’”

As a way to “rebalance my karma,” Miale began volunteering at a food pantry, which eventually led to leading cooking classes and ultimately founding a local chapter of Share our Strength. Miale wrangled a position for herself at the food bank by securing a grant on behalf of Good Shepherd, as well as a sponsorship from a local supermarket chain. “I ran the Cooking Masters program for two years and I absolutely loved it,” Miale said.

Meanwhile, the food bank was floundering, losing many of its top executives at once and running out of both food and money post-recession to meet growing need. Miale approached the interim president and offered her finance skills to lead a strategic planning process at no charge. “He’s like, ‘Aren’t you the cooking class lady?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, but I used to do this.’”

With strong backing from the interim president, Miale applied for the CEO job and won it by a narrow margin. With her financial and analytic background, she was able to bring a much more disciplined approach to the food bank’s operations and get the organization back on a strong financial footing. Her lack of knowledge about food banking also proved to be a plus. “I didn’t know what the sacred cows were,” she said. “Being an outsider almost made it easier to push through change.” – Chris Costanzo

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News

This article was made possible by the readers who support Food Bank News, a national, editorially independent, nonprofit media organization. Food Bank News is not funded by any government agencies, nor is it part of a larger association or corporation. Your support helps ensure our continued solutions-oriented coverage of best practices in hunger relief. Thank you!

Connect with Us: