How often do food banks roll out programs in which 95% of the targeted clients participate?

It’s happening in Florida, with nearly all of the 2,055 seniors signed up for a fruit and vegetable purchasing program taking advantage of it, according to the three partners behind the program. The program lets food-insecure seniors spend $15 a month on fresh produce at any local Walmart using a payment card that has been preloaded with the value.

The popularity of the program is perhaps not so surprising given its structure. The card works just like a gift card, making it easy for seniors when checking out at the register. By design, the seniors enrolled in the program can easily get to Walmart on their own or through public transportation. Perhaps most important, the program gives seniors the power to choose their fruits and vegetables as they go about their regular grocery shopping.

“The ability to integrate a solution into the normal course of how a person lives is really important,” said Matt Spence, Chief Programs Officer at Feeding Tampa Bay, the food bank brought into the program by Wholesome Wave, a national non-profit seeking to increase affordable access to fruit and vegetables via community partnerships. Humana Foundation is funding the nine-month program.

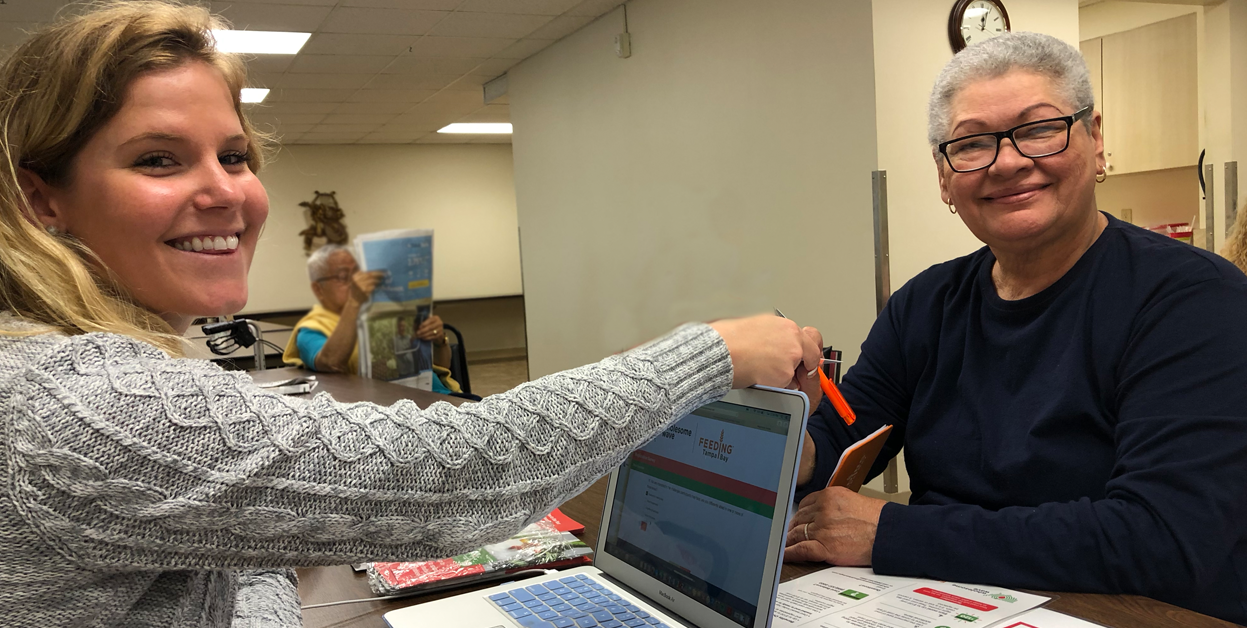

Feeding Tampa Bay used its on-the-ground knowledge of the local landscape to identify participants at low-income senior housing centers and meal sites, and signed them up face to face. “The project in our mind was complex enough that that personal touch was really important,” Spence said.

Indeed, nearly three-quarters of the seniors who signed up reported suffering from one or more challenges, including cognitive impairment, limited dexterity, or vision problems. “We knew that any solution we would bring to the table needed to be simple to understand, user-friendly and fit within their capabilities,” said Julie Peters, Programs Director at Wholesome Wave.

In addition to the payment cards, Wholesome Wave provided automated texts to remind seniors to use the cards and how to use them. Sending texts to seniors was a first for Wholesome Wave, which was happy to see that seniors understood and reacted to them. “That’s terrific input for future programming,” Peters noted.

On the back end, the partners are receiving valuable information about the types of food seniors are purchasing. Seniors are spending an average of just under $11 per trip and picking up about five items, with a near 50/50 split between fruits and vegetables. That data has been “incredibly helpful” for Feeding Tampa Bay, which is using it to stock distributions for other programs aimed at seniors, such as its mobile pantry, Spence said.

As the nine-month program begins to wind down (along with its funding), the partners are hoping they have succeeded in nudging seniors toward buying produce on a more regular basis. Ideally, the program has lowered the risks for seniors when spending limited funds on new types of produce, Peters said. “Once you get over the risk threshold and start to build it into your diet, then it’s possible to increase the number of servings, even on a restricted budget,” she said.

For Feeding Tampa Bay, the Wholesome Wave project has reinforced the importance of face-to-face sign-ups as it seeks to expand the number of senior SNAP users in its region. Only 40% of eligible seniors in Florida currently receive SNAP, Spence noted. Feeding Tampa Bay already has a staff that signs up seniors for SNAP in person, and recently began training its agency partners to do the same. “If we can train the community to do SNAP assessments and registrations, then we can multiply our effect,” Spence said.

ABOVE: Feeding Tampa Bay signed up seniors for the produce purchasing program face to face.