A quick look at the home page of Yolo Food Bank’s website underscores a main mission of its Covid-19 response: to get food to the elderly and vulnerable who are stuck at home.

In stepping up to meet the needs of low-income quarantined individuals, Yolo is taking on one of the most labor-intensive, logistically complicated food distribution tasks possible. Its coordinated response to meal delivery stands out among food banks, all of which are already struggling to meet unprecedented demand for their standard food distributions. Adding meal delivery atop the already staggering need feels too “daunting” to some food banks, and better left to entities with already-developed delivery capabilities, say others.

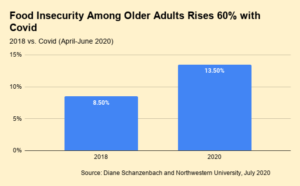

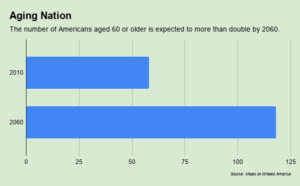

Even so, the need for home-delivered meals during the current pandemic is enormous. It’s reflected in the 650% increase in traffic over the last three weeks to the Find Meals page on Meals on Wheels America’s site. Even before the current crisis, about half of the nation’s Meals on Wheels programs had a wait list, with an average wait of about four months. With Covid-19, “programs saw more requests for service during the month of March than they typically see in an entire year,” said Jenny Young of Meals on Wheels America.

The need is also apparent in the massive, wartime-like response to meal delivery happening in New York City, which is turning to idled taxi, Uber and Lyft drivers to deliver about 100,000 meals a day, but needs to get to about one million meals a day, in the view of Hunger Free America. “We have to dramatically, dramatically, dramatically ramp up door-to-door meal distribution, possibly using the National Guard,” said Joel Berg, CEO of Hunger Free America.

In Yolo Food Bank’s corner of rural California, where it serves 35,000 people a month, the need for home delivery became obvious on Monday, March 9, as the food bank began mapping out its Covid-19 response plan. By that Friday, it had initiated a massive social media campaign to let people know it would deliver food to their doors. The following week it home-delivered 750 boxes filled with 45 pounds of food, and by week three, it was serving more than 4,000 people in 2,000 households, up from none before the crisis, said Joy Cohan, Director of Philanthropic Engagement at Yolo. “In short order, we adapted and expanded our service delivery model dramatically,” she said.

The food bank’s website makes its intentions clear: A big red button at the top of the page asks low-income individuals to fill out a short form to request a home delivery, and promises that all who apply and are accepted will receive weekly deliveries of food during the crisis. A second big red button below solicits volunteers.

The food bank has succeeded in quickly adding about 700 new volunteers to its effort and is also trying to solicit commercial vans and drivers who have been sidelined during the crisis. The volunteers arrive on a staggered schedule at one of four central distribution points where they pick up between seven to 12 boxes of food and a list of where they should be delivered. Before setting off, the volunteers call everyone on their list, to let them know a delivery is imminent over the next couple of hours. Once at the home, they put the box down, knock and walk away, then make a second call from their car to confirm the delivery.

Yolo Food Bank is not making people go through hoops to qualify for the program. Whether applying online or over the phone, applicants are asked only two questions: whether they are low-income and over 65, or if they are low-income and health-compromised. “It’s something of an honor system,” Cohan noted. “We would always err on the side of serving the few who didn’t need it, versus miss anyone who really needed it.”

Cohan credits the food bank’s proactive planning for its ability to successfully launch the delivery program. “The smartest decision we made was to be ahead of the curve and anticipate what might happen versus let it happen to us,” she said. The community has also come through with donations, though Cohan is actively looking at various funding models to sustain what is expected to be an ongoing need.

Yolo is far from the only food bank stepping up to meet the need for home deliveries. The Food Bank of Santa Barbara County has delivered groceries to the homes of more than 3,400 seniors over the past month. Three Square Food Bank in Las Vegas is tapping county legislators and city council members to make home deliveries, knowing they are already background-checked and would likely offer reassurance to seniors during deliveries. The Food Bank for Larimer County in Colorado recently redirected four of its 26-foot refrigerated trucks that normally recover retail food to instead deliver monthly food boxes to seniors.

Yolo, however, may stand apart in making home deliveries a centerpiece of its Covid-19 response effort. “There’s no way around the fact that it hasn’t been a heavy lift,” Cohan said. “We didn’t feel it was a choice to say we couldn’t feed people.”

Do you have a plan for feeding the homebound during Covid-19? Let us know: email chris.costanzo@foodbanknews.com.

Connect with Us: