Giving food pantry clients the ability to choose their own food can feel like a big undertaking, but Lowcountry Food Bank of Charleston, S.C., has developed a flexible, hands-on approach that’s helping pantries in its network make that move one baby step at a time.

About 30% of the 60 pantries in the food bank’s three-county Northern Region are now operating a choice model, thanks in large part to the efforts of Kari Hanna, Agency Relations Manager, and Suzy Johnson, Nutrition Education Coordinator. (The food bank has more than 230 pantries throughout its ten-county operating area.)

The key to driving change in its Northern Region was a combination of small, incremental steps and a whole lot of handholding. “It takes a lot of patience,” Hanna said. “But really just working with them at the speed that they’re comfortable with as far as making those changes.”

The biggest factors impacting whether a pantry can – or as Hanna emphasized, thinks it can – offer more choice are size and space. But change itself can also be a hurdle. “We’ve had agencies that have been open for twenty years and they’ve done it the same way,” Johnson said, a mindset that makes change hard.

Working with the choice continuum articulated by Feeding America’s Choice Capacity Institute, Hanna and Johnson begin by evaluating whether a pantry is ready to implement choice. “Do we think that they have the space, the volunteers, the willingness to do it? Or even just maybe that they have the interest to do it?” said Hanna. If the answer is yes, the pantry progresses to the next critical stage – an on-site needs assessment.

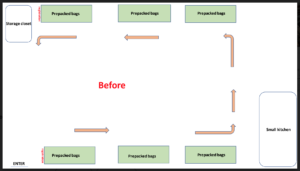

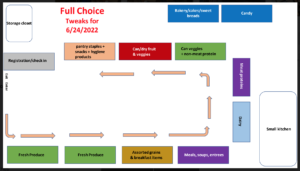

In the assessment phase, Hanna and Johnson evaluate the pantry space, discuss what the pantry envisions in terms of choice, and guide the pantry through how choice distributions could work. The order in which neighbors encounter food items in the pantry is critical. “We want them to start with the fresh stuff first,” Johnson said. The result is a “pantry flow” diagram – a schematic of a revised pantry layout, showing how neighbors would move through the space in a choice distribution.

More often than not, implementing choice is an incremental process that involves what Hanna and Johnson call “baby steps.” Said Hanna, “We start out by just getting them to offer one item that’s a choice. So maybe they pre-pack a bag and they start offering bread and bakery items as a choice,” Hanna said. “It’s just these small steps until they start to see, ‘Okay, this isn’t that bad. We can do this.’”

Mary Magedaline Outreach in Lane, S.C., is an example of the process in action. Hanna’s first step was to convince the pantry – basically a one-woman operation with a few volunteers serving about 20 neighbors – that it had the capacity to open twice rather than once a month. From there, Johnson created a series of pantry flow diagrams showing how the pantry could gradually replace its six tables of pre-packed bags. Starting with two choice tables and guided by the diagrams, the pantry evolved over four months into a full choice pantry.

The process involves a lot of discussion, Hanna noted. “It might be months of talking first. Or having them visit another pantry, or talking with their board, or talking with their pastor.” The Samaritan House in Conway, S.C., for example, “was a little bit more hesitant” about changing a process that had worked for years, she said. A series of meetings, helped by Johnson’s pantry flow diagrams, resolved those concerns.

“We essentially just overhauled their whole space and turned it from a pallet storage area to a miniature grocery store,” Hanna said. With help from a Food Lion pantry-makeover grant, Hanna and Johnson equipped The Samaritan House’s existing space with shelving, a produce cooler display case, and a three-door, glass-front refrigerator. They also trained pantry staff and volunteers through “education days” that included tours and training on nutrition, inventory management, and ordering.

Hanna and Johnson emphasize the move toward choice is a process. “It’s not going to be perfect at the beginning. You’re going to have to learn what your neighbors want, what they don’t want,” Hanna said.

Choice pantries in the food bank’s Northern Region are seeing the benefits. They’re becoming adept at rotating products and keeping shelves stocked, Hanna said, and spending less time packing bags, which has translated into expanded hours that better suit neighbors’ schedules. “Everyone’s pleasantly surprised with all the operational aspects once they get going,” Johnson said.

Lowcountry’s operations are benefiting too. “[The pantries] have a better understanding of how to place an order that makes sense for their neighbors putting together meals, and not just ordering a bunch of everything,” Hanna said.

Pantries need to feel heard and supported, both initially and throughout the process, Hanna and Johnson noted. “In those initial meetings with the partners, I think the most important thing is to listen to what they’re telling you they need or that they want,” Johnson said.

Added Hanna, “Letting them know ahead of time that, Hey, we’re gonna be here through the whole thing. You’re probably gonna get sick of us. But we’ll be there.” –Amanda Jaffe

Amanda Jaffe is a writer and former attorney with a deep interest in organizations and mechanisms that address food insecurity. Her online publication, Age of Enlightenment, is available on Substack, and her essays and articles may be found at www.amandajaffewrites.com.

CAPTION FOR PHOTO, TOP: The Samaritan House in Conway, S.C., now features a display case so clients can choose their produce.

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News