When Greater Vancouver Food Bank decided to do away with traditional food drives, it was perfectly clear about why. It proclaimed on social media and its website that up to 30% of the food it received from food drives was spoiled, damaged or unsafe to eat.

In addition, it said, most of the food it received from food drives was unhealthy. Plus, transporting and sorting so many random items of food was highly labor-intensive. And the food bank knew it could buy more and better food on its own through high-volume purchases with industry partners.

Greater Vancouver Food Bank may be more direct than most in explaining its approach, but it’s not alone in rethinking traditional food drives. An increasing number of food banks are exploring ways to minimize the downsides of standard food drives, while still tapping into the instinct of individuals who want to give to relieve hunger.

Greater Vancouver Food Bank may be more direct than most in explaining its approach, but it’s not alone in rethinking traditional food drives. An increasing number of food banks are exploring ways to minimize the downsides of standard food drives, while still tapping into the instinct of individuals who want to give to relieve hunger.

One way of minimizing unwanted food items in a food drive is to steer donors toward healthier foods. A food pantry in rural Kansas is doing that through a partnership with a local co-operative grocer.

South Barber Food Bank and Hometown Market in Barber County, Kan., are using color-coded stickers to show donors and grocery shoppers the healthiest options. Tagging items as “food-pantry preferred” not only encourages community members to shop for healthy options for those in need, but forges stronger community ties.

The tags, as well as donation receptacles and promotional materials are part of a grant-funded effort to get healthier food onto the pantry’s shelves. In addition to making donors aware of the need for healthier food, the pantry is using the SWAP (Supporting Wellness at Pantries) system, which classifies pantry offerings into green, yellow or red, signifying foods to choose often, sometimes and rarely based on their nutritional quality.

When South Barber Food Bank assessed its pantry’s inventory according to SWAP, it found that 46% of donated food fell into the red (or rarely) category, compared to 8% for purchased food. By using the grocery tags – yet still recognizing that donors can donate whatever food items they like – the pantry hopes to reduce the amount of red food donated to 25% or less.

The push toward healthier food drives appears to be dovetailing with growing interest by donors to be more intentional in their food giving. The food pantry’s partner, Barber County United, designed a 14-question donor survey asking about interest in making donations and previous knowledge of food drives, said Debra Kolb, Director. The results showed that 73% of donors were interested in donating healthier items and learning more about the program.

“The initiative as a whole affected people’s buying habits before we even got the tabs up,” Kolb said. “Word of mouth in small towns can move fairly quickly.”

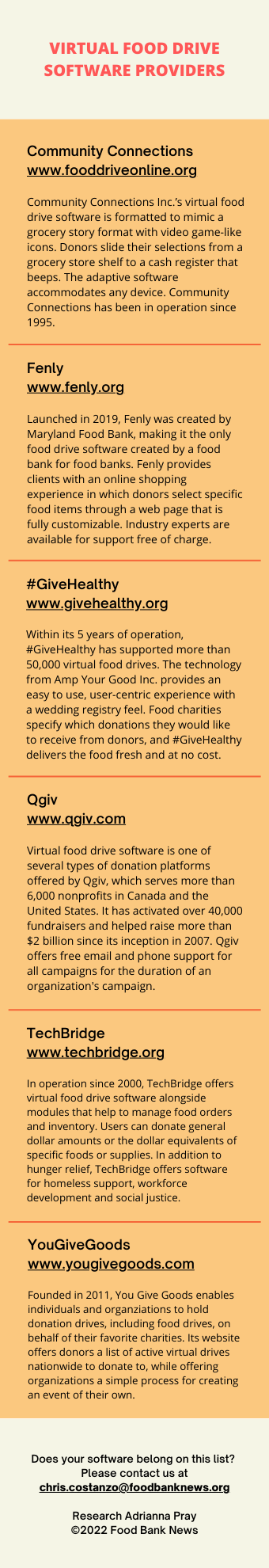

Virtual food drives have also emerged as an effective way to push donors toward healthier food choices. Donors pick from a pre-selected list of foods that reflect a food bank’s or pantry’s most desired items. The donations usually (but not always) result in a cash donation being the ultimate result, making it possible for food banks to employ their strong purchasing power to buy healthy foods, while also avoiding the hassle of dealing with unwanted items. (See our list of virtual food drive software providers at left.)

Moving to fund drives over food drives has worked out well for Greater Vancouver Food Bank. “We expected some pushback from people who’ve been doing them for a long time or workplaces,” said Terra Paredes, Manager of Community Events and Engagement at Greater Vancouver Food Bank. “But we’ve had very, very little negativity around the decision to drop food drives altogether.”

Virtual food drives reduce the likelihood of receiving cheap, processed food as donations. “One of the things that we talk about a lot is that people who are food insecure can buy those cheap and plentiful things,” Paredes said. “What we want to do is provide them with the things that they can’t buy for themselves — the proteins and the dairies and all of the produce. Those are the really expensive things right now.”

The Food Bank of Western Massachusetts moved toward virtual food drives in the early stages of the pandemic, in a decision mainly driven by safety, Director of Philanthropy, Jillian Morgan said. Soon after establishing a virtual method, however, food storage issues prompted a more permanent switch.

“It’s freeing up some of our capacity for volunteers to do other sorting and packing jobs. It has cleared space on our floor that would usually be taken up with salvage and those kinds of one-off individual items,” Morgan said. As a result, the food bank is now able to store more of the food that it’s buying in bulk.

These days, the food bank rarely opts to host a food drive instead of a fund drive, but has made some exceptions. More often than not, it will connect an organization directly to a pantry in its member agency network.

“We were never really in a position to bring back the food drive donations” after the pandemic, Morgan said. At the same time, virtual food drives have helped the food bank be able to increase its distribution of produce, dairy, and other healthy and culturally relevant products throughout the network. – Adrianna Pray

Adrianna Pray is a journalism student at Emerson College. In addition to Food Bank News, she writes for Emerson College’s student newspaper, the Berkeley Beacon.

CAPTION ABOVE: Greater Vancouver Food Bank’s website, explaining why it’s moving away from traditional food drives.

Here are the links to the virtual food drive software providers:

fooddriveonline.org

fenly.org

givehealthy.org

qgiv.com

techbridge.org

yougivegoods.com

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News