When the Stamp Out Hunger food drive, usually held the second Saturday in May, was postponed because of Covid-19, it was the largest food drive in the country to be suspended, but far from the only.

The shuttering of the Stamp Out Hunger drive, organized annually by the National Association of Letter Carriers, meant that about 1.75 billion pounds of food would not be going to local food banks and pantries around the country. Food banks are also feeling the loss of their own spring food drives. St. Mary’s Food Bank in Phoenix, Ariz., for example, cancelled 19 out of its 37 planned food drives in March, resulting in a loss of 50,000 pounds of food.

With the pandemic continuing to inhibit in-person food drives for those who are sheltering in place and social distancing, virtual food drives, in which donors go online to select and pay for donations of specific types of food, are gaining a greater foothold.

“We’ve seen a 10-fold increase of donations on the platform itself,” said Jami Dodson, Vice President of Marketing at Maryland Food Bank, which built a virtual food drive software program called Fenly, which it runs and also sells to other food banks.

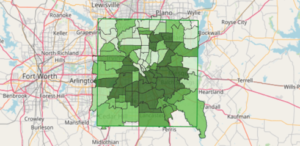

In recent months, East Texas Food Bank has organized around a dozen virtual food drives through the Fenly system, raising some $17,000 in donations. Overall, it has raised more than $30,000 in donations through the platform, which translates to more than 250,000 meals, according to Michael Hetrick, Communications Manager.

While traditional food drives sometimes result in donations of outdated or less healthy food, virtual food drives offer the benefit of allowing food banks to steer donors to most-needed items. They work somewhat like a wedding registry, depicting a food item in quantity — say 24 jars of peanut butter — and the amount that would cover its cost.

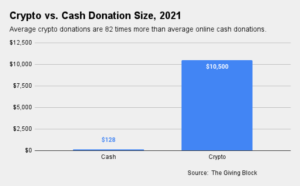

One result of soliciting bulk-item donations is that donors tend to give more. Patrick O’Neill, CEO of Amp Your Good, which offers the #GiveHealthy virtual food drive software, said that on average donors give 25 to 30 pounds of food through #GiveHealthy, which is more than is typically donated when donors must physically transport the food.

Virtual food drives can also encourage donations of cash, allowing food banks to take advantage of their wholesale buying power. Hetrick of East Texas Food Bank noted that people like giving tangible goods to pantries, but ultimately cash gifts give food banks a lot more flexibility. “We can use that money however we see fit, whether to purchase food throughout our 26 counties or for transportation and storage of food,” Hetrick said. “Virtual drive money is unrestricted.”

Online food drives offer another advantage: contagious giving. Hetrick believes donors are more likely to participate if they see their friends and family giving. “That’s the power of social fundraising,” he said.

Maryland Food Bank decided to build the Fenly software when it realized it had a need, shared by many food banks, for a solution that could combine peer-to-peer fundraising, crowdfunding and virtual food drives all on one platform. In its view, the online tools available to food banks at the time were too antiquated and unaffordable. Fenly currently has 12 customers and since March has seen an uptick of about 250% in the number of users on its platform.

Another provider, TechBridge of Atlanta, offers a variety of software products, including online ordering, inventory management and virtual food drive software. “Virtual drives are easy and fun for nonprofits to generate online cash donations or show the equitable meals their cash is actually going to purchase and how many people it is going to feed,” said Manish Misri, Vice President of Technology at TechBridge. Virtual drives also offer more control than physical drives by allowing food banks to solicit certain types of food or match needs with supply, he said.

At #GiveHealthy, yet another upside to the virtual model is being able to cut down on the work required for organizers, while reducing the need for volunteers. Once a #GiveHealthy food drive ends, #GiveHealthy takes care of everything, purchasing all the food indicated by the donors, giving the food bank a heads-up on exactly what foods to expect and scheduling a delivery time. It also provides a list of who donated, bolstering future fundraising efforts.

#GiveHealthy focuses specifically on the donation of fresh fruits, vegetables and other healthy foods in a bid to change the culture around food drives, which in the past has often resulted in donations of nutrient-light, canned food. Since the beginning of the pandemic, #GiveHealthy has seen a four-fold increase in usage of its service, with March being particularly busy, said O’Neill, who also is a Food Bank News board member.

While virtual food drives are getting more attention during the crisis, the hope is that they remain in the spotlight even after the crisis ebbs. “In natural disasters in the nonprofit world, there’s a lot of support quickly,” noted O’Neill. “And then it goes away, But the need for food support will continue.” — Antoinette Siu

Antoinette Siu is a Bay Area journalist covering business and policy. Antoinette has been published in The Washington Post, San Francisco Examiner, San Francisco Business Times, International Business Times and featured on local and state radio.

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank NewsConnect with Us: