Home delivery looks to be at an inflection point.

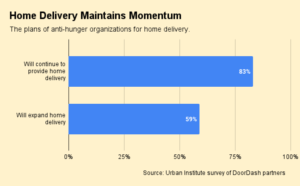

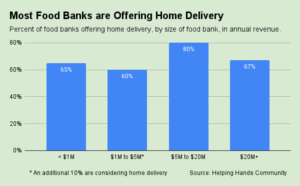

Many hunger relief organizations took home delivery from zero to sixty in recent years, fueled by pandemic demand, as well as generous aid from government and private companies like Amazon and DoorDash. Now, as some of that aid dries up, there is both greater commitment to home delivery than ever before, as well as greater uncertainty about whether it can be sustained.

Greater Cleveland Food Bank’s pathway into home delivery was fairly typical. When the pandemic broke open a sudden need for hundreds of home deliveries a week, it first engaged the National Guard, and then tapped volunteers led by a full-time home delivery coordinator, a position created in summer 2020.

About a year ago, DoorDash came onto the scene, making it possible for the food bank to use the food delivery service’s drivers and routing technology at no charge. Before long, the food bank was making 1,000 deliveries a month, mostly to seniors, up from about 200 a month before DoorDash, according to Lisa Laditka, Director of Outreach and Community Partner Services.

Central Pennsylvania Food Bank similarly ramped up its home delivery program, initially addressing some of the need for home delivery through local partnerships with Meals on Wheels and Area Agencies on Aging. The program really gained steam about a year ago when DoorDash offered up its services for free, enabling an additional 9,300 home deliveries last year, for a total of about 12,000 deliveries, said Tara Davis, Director of Agency Services and Outreach.

In all, DoorDash has partnered with more than 50 food banks across the country and hundreds of local pantries to deliver more than 60 million meals since 2018, said Daniel Riff, Senior Manager, Government and Nonprofit at DoorDash. Amazon, meanwhile, delivered about 10 million meals in 2022 on behalf of about a dozen U.S. hunger-relief partners, said Josh Hirschland, Principal Product Manager.

As food banks have gotten more involved in home delivery, they’re more aware than ever of the difficulties of supporting that need. Funds related to Covid relief can only last so long, and private companies cannot be counted upon to consistently pick up the tab. At the end of 2022, for example, DoorDash notified its hunger relief partners that it no longer would be providing its home delivery services for free, indefinitely.

The company, which has espoused the need for home delivery to be sustainable, has come through with grants, which in many cases will support several months of free home deliveries, as well as low-cost subsidized deliveries. Despite this support, many food banks will be bearing much more of the cost burden for the now-heightened demand for home delivery.

How will they meet it?

At Greater Cleveland Food Bank, the grants provided by DoorDash will support home deliveries at least through the first quarter, Laditka said. Then, the food bank will start tapping into funds that have been budgeted for Covid response. Meanwhile, the food bank’s fundraising team has been engaged to search out additional grant and funding opportunities. Laditka figures the food bank will need about $275,000 annually to fully support home deliveries, including the costs of food, staffing, deliveries, as well as incidentals like signage and automated calls to notify recipients that their food has been delivered.

Between the grants from DoorDash and extra dollars in its current budget, Central Pennsylvania Food Bank expects it will be able to continue its current level of home deliveries through this fiscal year. At the same time, it also is turning to its development team to see about fundraising for next year.

In addition, it will continue to seek out new partnerships to help it cover its 27-county, mostly rural service area. Recently, a council of local labor unions has stepped in to take care of a large swath of deliveries, a relationship that Davis described as “absolutely wonderful. They’re familiar with the area and they’re doing this because they really want to,” she said.

In another partnership, the food bank is working with a healthcare provider that uses United Parcel Service (UPS) to do overnight food deliveries to patients identified as food-insecure. The cost of those deliveries is covered by health insurance, Davis said.

Whether smaller organizations with fewer resources will be able to continue supporting home deliveries once outside aid fades away is less clear. Daily Bread Food Pantry of Danbury, Conn., is now doing about 20 home deliveries a week by taking advantage of DoorDash drivers. The volume is small enough that the pantry expects it will be able to continue the service even once its grant allocation gets used up. “But we’re certainly not planning to scale it up much more than what we’re currently doing,” said Peter Kent, President. He noted that for smaller organizations, the burdens of packing boxes and dealing with administrative tasks can be limiting factors on top of the cost of deliveries.

Food Bank of Delaware has relationships with both Amazon and DoorDash for home delivery, which gives it some flexibility as it looks to the future. The food bank made 41,000 deliveries in fiscal 2022, with Amazon Flex drivers all over the state executing about 90% of the total, said Kim Turner, Communications Director. The food bank covers the cost of the food, and has a home delivery manager and two staffers to support the program. Amazon makes the deliveries for free, and also has made a $50,000 donation to the food bank. “It’s been a game changer for us,” Turner said. Because DoorDash makes up such a small portion of the total home deliveries, the food bank will either do additional fundraising, or send those deliveries through Amazon, if necessary, Turner said.

Amazon is also helping the Central California Food Bank expand its home delivery program. Since September, the food bank has partnered with Amazon to do “last-mile deliveries” to about 400 households a month, said Natalie Caples, Co-CEO. Recently, the food bank submitted a proposal to the county government to obtain funds to greatly expand its program. “Our goal is to bring some delivery in-house with a van and a driver, and fill in the gaps where Amazon is not currently delivering,” Caples said. At the same time, Amazon is expanding its delivery radius, she noted.

Hirschland of Amazon said the company is running its charitable home-delivery program just as it does its for-profit businesses, using the same tools, processes and review mechanisms. It has committed to working with its current partners for home delivery through 2023 and “fully expects to go beyond that,” Hirschland said. The company also anticipates onboarding new food-bank partners in the coming months, he said.

While it’s not clear exactly how food banks, and especially food pantries, will be able to support home delivery over the long run, hunger relief executives contend that home delivery is here to stay. “Everybody’s well aware that senior populations are on the rise, and we have to have programs in place to support them beyond the expectation that they all leave their houses to go get food,” said Laditka of Greater Cleveland Food Bank. As a result, “people will become much more conscious of the fact that home delivery is going to be built into budgets.”

Private companies like DoorDash and Amazon get credit for highlighting the need and pushing food banks to do more deliveries than they ever thought they’d be able to, the executives said. “We knew home delivery was something that we needed to do,” said Davis of Central Pennsylvania Food Bank. DoorDash helped “jumpstart” the food bank’s efforts to a higher level, she said.

Given uncertainties around funding, home delivery may not grow as fast as it once did. But the current level of commitment by food banks may well remain. “Now we have seniors relying on the box,” Davis said. “To just say, ‘no more,’ that wouldn’t feel right to us.” Agreed Laditka, “I don’t think there’s any way to eliminate what we’re doing now.” – Chris Costanzo

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News

This article was made possible by the readers who support Food Bank News, a national, editorially independent, nonprofit media organization. Food Bank News is not funded by any government agencies, nor is it part of a larger association or corporation. Your support helps ensure our continued solutions-oriented coverage of best practices in hunger relief. Thank you!

Connect with Us: