When Second Harvest Heartland of Minneapolis gave itself the goal of cutting hunger in half by 2030, it struggled mightily with defining exactly what success would look like.

Would it succeed when people could get the food they needed by going to a pantry or using SNAP? Or would it succeed when people had enough food without even thinking about getting some sort of assistance? For the person experiencing hunger, what did it mean, exactly, to reduce or end it?

Traditionally, researchers have tended to treat hunger as a binary condition – you are either hungry or you are not. But the more Second Harvest Heartland thought about it, the more it saw hunger as a continuum. People tend to experience it in a dynamic way, becoming more or less hungry depending on how much money they have to buy food, as well as how easily they can get assistance if they need to.

The desire to know more about exactly how people experienced hunger led Second Harvest Heartland to come up with a brand new way of defining and measuring it. With its more granular measurement, the food bank is hoping to identify better solutions to hunger.

“We’re establishing new definitions and we’re also changing the goal in terms of outcomes,” said Zach Rodvold, Director of Public Affairs at Second Harvest Heartland.

The food bank’s research, based on surveys and interviews with about 3,000 people with lived experience, identifies four possible stages of hunger, bringing more clarity to exactly how people experience it. The first two stages describe households that do not have enough food. Those in Stage 1 (2%) don’t have enough food and are not accessing any food assistance, while those in Stage 2 (5%) are accessing some assistance, but still not enough. The people in these two stages fit the definition of hungry, according to Second Harvest Heartland.

The largest percentage of households (81%) is in Stage 4 and has enough food without assistance. That leaves Stage 3, which is the most intriguing to Second Harvest Heartland. These households (13%) have food, but only because they are successfully accessing enough outside assistance. Second Harvest Heartland defines these Stage 3 households as food insecure (but not hungry).

The distinction between hungry and food-insecure households is important because it dictates different solutions. The people in Stages 1 and 2, who are hungry, clearly need better access to food assistance. Those in Stage 3, however, could be candidates for other types of solutions that might alleviate their need for assistance in the first place and ideally push them into that fourth stage of food security.

“If the goal is to feed hungry people, then the way you budget and invest and build your teams all looks very different than if the goal is to have fewer hungry people,” Rodvold said. He added, “We want to do everything we can to meet today’s need, but we also need to decrease that need over time.”

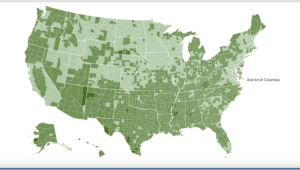

To that end, Second Harvest Heartland is embarking on an intense exploration of how to prevent food insecurity in the first place. The process will begin with data mapping to identify high-need “hunger hot spots” and will include partnering with nonprofits outside of hunger relief, as well as academics, think tanks, the private sector, and the food bank’s own Neighbor Advisory Council to identify the most effective interventions in those communities.

Ideas on the table include interventions that would boost peoples’ resources, like wage or tax policies; those that would help reduce costs, like childcare subsidies or rental assistance, and those would improve support systems, such as access to mental or physical health aids, or even transportation. “We’ll crowdsource the best ideas from all of the stakeholders, and then pick no more than a handful to dive into over the next year,” Rodvold said.

Second Harvest Heartland worked with a research firm to conduct its survey, which asked 19 questions to about 20,000 people (with about 3,000 responding) and cost about $200,000 to execute. It plans to conduct the survey every year. With 19% of its population currently experiencing food insecurity, Second Harvest Heartland will be working on its goal of cutting hunger in half by having 90% of Minnesota households be food secure by 2030.

The food bank’s promotion of a new way to measure hunger raises questions about the more traditional measurements, such as the USDA’s survey of household food security and Feeding America’s annual Map the Meal Gap, which was released last month. Karen Spitzfaden, Director of Consumer Insights and Digital Strategy at Second Harvest Heartland, noted that the USDA statistics carry a lag of one to two years, making them difficult to work with.

And Map the Meal Gap is not precise enough in describing the way people experience food insecurity, she said. “We don’t actually understand what is true about the people who Map the Meal Gap says are food insecure,” Spitzfaden said. “Are they coming to food shelves? We don’t really understand what is going on here.”

Defining food insecurity as part of a continuum adds a new element to the conversation, acknowledged Rodvold. In the past, food-insecure people who successfully got food assistance “have always been treated as food-secure, so the work sort of stopped there,” he said. The food bank’s new definition broadens the scope of the work it is doing, letting it lean in on prevention. “It is a broader effort that’s needed,” Rodvold said. “We’re raising our hand to say we’re willing to put a stake in the ground here and invite people to join us on this journey.” – Chris Costanzo

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News