There’s no doubt that the new ability in some states to tap Medicaid money as reimbursement for nutrition services is attracting attention from the hunger-relief community.

But there’s another legislative mandate that is having a more immediate impact on food-bank partnerships with healthcare organizations. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has decreed that by 2024, all hospitals and clinics in federal payment programs must screen their patients for social determinants of health, including food insecurity.

The stipulation is sure to result in the detection of many more food-insecure households, which in turn will be referred to local hunger relief agencies. “There’s going to be an influx of referrals from providers to CBOs [community based organizations],” predicted Amanda Bank, MPH, Program Associate at the Center for Health Care Strategies, a N.J.-based nonprofit that aims to improve health outcomes for Medicaid enrollees.

The ruling adds to the imperative that food banks strike up relationships with local healthcare providers. In April, the Center for Health Care Strategies issued a report on ways to strengthen these relationships, which “will require mutual understanding, trust between organizations, and viable operational and financial agreements,” Bank noted.

Some food banks have already begun working to build connections with their local healthcare organizations. Long Island Cares, for example, has taken a systematic approach, reaching out to each of the three main healthcare providers that operate on the island. For one hospital, the food bank is running a mobile pantry that delivers food twice a week to the homes of about 80 people who have been discharged, but don’t have access to food or community support at home. It also provides emergency food bags to the emergency rooms of another healthcare provider, and to the pediatrician’s offices of another, along with monthly nutrition workshops.

“You’re going to see more and more alliances like this pop up,” said Jessica Rosati, Ph.D., Vice President for Programs at Long Island Cares. “It just makes sense for our two industries to work more closely together for the people we serve.”

In Pennsylvania, Chester County Food Bank is working with ten community healthcare clinics to supply their patients with payment cards that can be redeemed for fruits and vegetables at the food bank’s mobile market. The cards hold an average of $400 and can be used throughout the growing season of June to October. So far, the food bank is serving about 320 households through the program, and would like to expand it by another 150 or so households, as well as make it possible to redeem the cards at local farmers markets.

“We consider healthcare providers to be one of our key food access points,” said Andrea Youndt, CEO.

Food banks considering partnerships with healthcare providers have a number of entry points. The Food is Medicine Accelerator program, which is working to make medically tailored meals more widely available, acknowledges that not every hunger relief organization is prepared to take on the rigor that a medically tailored meal program requires. So far, 14 organizations, most of them food banks, have completed the Accelerator’s training process and are at various stages of getting a medically tailored meal program off the ground, said David B. Waters, CEO of Mass.-based Community Servings, which runs the Accelerator along with NYC-based God’s Love We Deliver and other organizations.

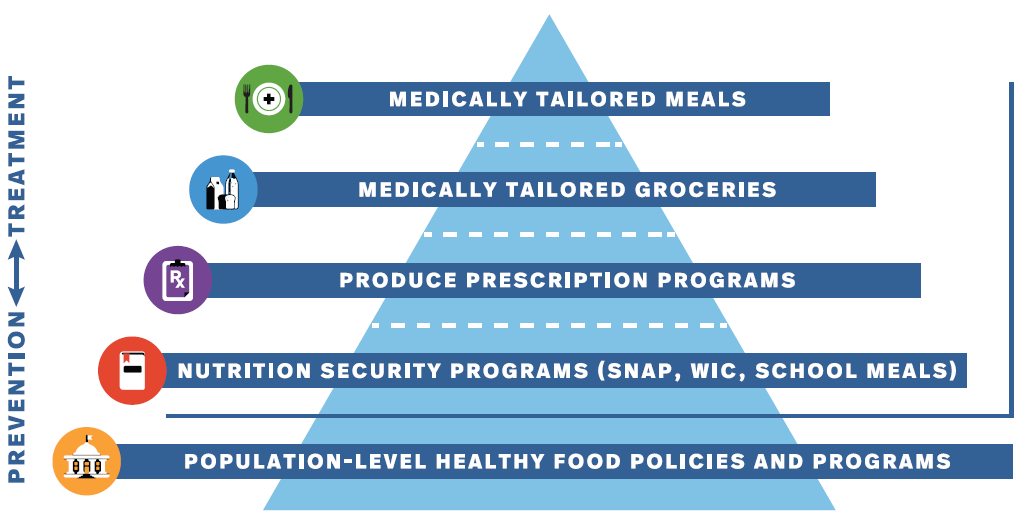

Most food banks, however, are at much earlier stages of working with healthcare partners on Food is Medicine initiatives. According to the Accelerator, instituting healthy food policies and supporting programs like SNAP qualify as early-stage Food is Medicine initiatives (see chart, above). More advanced efforts include offering produce-prescription programs and medically tailored grocery bags. At the very top of the pyramid are medically tailored meals, which are appropriate for about 5% of the population. “There are an array of program interventions, all of which are important,” Waters said.

Having a broad array of options is not necessarily a good thing for food banks seeking to partner with healthcare providers and also be good stewards of their resources, noted Pat Curtin, Founder of Point Sur Consulting, a food bank consultancy based in Chicago. Partnerships between food banks and healthcare providers can be extremely complicated, raising issues around technology, data sharing, client privacy, service models and success metrics. “How can we optimize the resources of the food bank where the food bank is able to handle this increased responsibility at the least risk?” asked Curtin.

Funding pathways are also a big consideration. Long Island Cares has gotten funding in three different ways for each of its partnerships, including state funding, grant funding and direct funding from one of the hospital partners. Chester County Food Bank, meanwhile, is investing about $150,000 annually in its prescription cards and looking for ways to sustainably grow the three-year-old program.

Food banks should be thinking strategically about funding, Curtin said, noting that partnerships between healthcare and hunger relief have the opportunity to bring about transformational change in terms of client outcomes. He asked, “What are the value-added proposals that you can develop so that hospitals and health plans will invest in your approach?” – Chris Costanzo

Chart above is courtesy of Food is Medicine Coalition.

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News