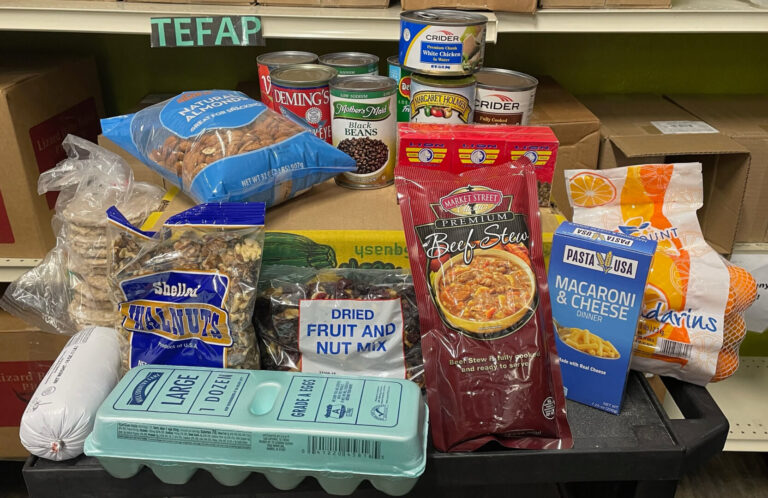

It’s fair to say that most food banks generally appreciate the Emergency Food Assistance Program.

It’s the only federal nutrition program specifically geared toward food banks, providing them with a wide variety of fresh, frozen and canned foods. Most of the food is healthy, and all of it comes from U.S. growers and producers. Feeding America calls TEFAP a “cornerstone” of its food supply, providing about 30% of the food distributed through its network and offering access to more than 120 nutritious foods.

Even so, small pockets of resistance toward TEFAP exist. That’s because of certain requirements placed on people receiving the food. The federal government asks that people receiving TEFAP food submit four pieces of information, including name, number of people in the household, address, and a declaration of income. States can and do add on their own requirements, such as verification of income.

That information-gathering doesn’t sit well with some hunger relief organizations.

West Side Campaign Against Hunger in New York City, for example, is required to have its customers sign off every year that they are living below a certain income level. “We say that having to attest once a year that you’re living in poverty is one time too many,” said Greg Silverman, Executive Director, during his keynote speech at the New York State Food Summit last month. “That’s not dignity.”

Alyson Rosenthal, Chief Program Officer, also acknowledged West Side Campaign Against Hunger’s strategic decision not to accept TEFAP during a presentation at last month’s Anti-Hunger Policy Conference. “It’s against our value set to create barriers to food,” she said. “The attestation of income is just not how we want to run our food pantry. So until those rules get changed, we are no longer accepting TEFAP and that’s not part of our programming.”

That value set also aligns with how Second Harvest Foodbank of Southern Wisconsin thinks about data collection related to TEFAP. “Philosophically, we don’t collect data on an individual level from any of the folks who come to our mobile pantries or any of our programs,” said Michelle Orge, President and Executive Director. “We believe, and our board has believed for many years, that collecting data is a barrier to food.”

Soon, Second Harvest will begin receiving TEFAP food and redistributing it to some of its partners, which in turn will hand it out to clients. But it will never distribute TEFAP food to its own mobile pantries, school markets, kids cafes, or other distribution outlets that it operates, Orge said. “If you let us in on the TEFAP contract, you’re going to hear from us about our disdain for the amount of data that you’re requiring to be collected,” she said.

Northwest Harvest, based in Seattle, Wa., is also opposed to data collection. In fact, it won’t take any government contract or grant that requires it to do reporting, including TEFAP, said Thomas Reynolds, CEO. If it can’t get waived from the reporting requirements, then it won’t accept the contract or grant.

“It’s not because we think reporting is bad,” Reynolds said, noting that there’s nothing sinister about providing information when the service makes sense, such as an address for home delivery. “What we recognize is that for some people, providing information could be terrifying and could be life-changing. And so we offer the alternative to people who do not need to be documented to have a place to go.”

Reynolds questioned the government’s purpose for collecting personal data in the first place, given that many other sources for it, such as tax returns, already exist. Northwest Harvest was able to get “phenomenal insights” from research conducted by the University of Washington, including dietary preferences, household sizes, and the number of households represented in a car traveling a distance in a rural area to get food.

“I would say the purpose and the utility behind reporting can be achieved in a better way,” Reynolds said.

For the vast majority of food banks, TEFAP’s role as a reliable source of nutritious food far outweighs any considerations about data collection. Food banks widely agree that TEFAP should get more funding, with Feeding America urging an increase to more than $700 million in the upcoming farm bill to cover food, as well as related storage and distribution costs.

Food banks are also taking various steps to improve TEFAP. Capital Area Food Bank, for example, recently produced a report aimed at making access to the program more equitable between states. Acting upon that idea, Facing Hunger Foodbank and God’s Pantry Food Bank in the neighboring states of West Virginia and Kentucky eliminated differences in income eligibility between their states, allowing residents of both states to access TEFAP food no matter where they live or work.

Michelle Douglas, CEO of Emergency Food Network, an independent food bank south of Tacoma, Wa., said she has been part of a group working to reduce barriers to accessing TEFAP. Among the changes implemented: “There can no longer be a required signature, you don’t have to present ID and you absolutely do not have to present an electric bill or anything like that,” she said. “In general, we’ve been trying to reduce every single barrier” to TEFAP, though a self-attestation of income is still required.

Paule Pachter, CEO of Long Island Cares in New York, said that clients of Long Island Cares’ partner agencies and of the six pantries that it operates itself have not pushed back on the information they’re required to give to receive TEFAP food. TEFAP has become a significant source of food for Long Island Cares, which estimated it would bring in more than 3.5 million pounds of TEFAP food this year, an increase of about 39% from last year. “We continue to see an increase in the amount of food that we’re able to procure through the USDA and the quality of the food continues to improve,” Pachter said. As is true for most food banks, TEFAP “is something we rely upon,” he said. – Chris Costanzo

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News