WASHINGTON D.C. – If you’re thinking about ways to get into Food is Medicine, you might consider reaching out to your state’s primary care association as a first step.

Every state and territory in the country has an association of primary care providers, according to Patricia Quinn, Vice President of Policy and Partnerships at DC Primary Care Association, who spoke at the Anti-Hunger Policy Conference this week. “You can go to that primary care association and say, ‘How do we partner?’”

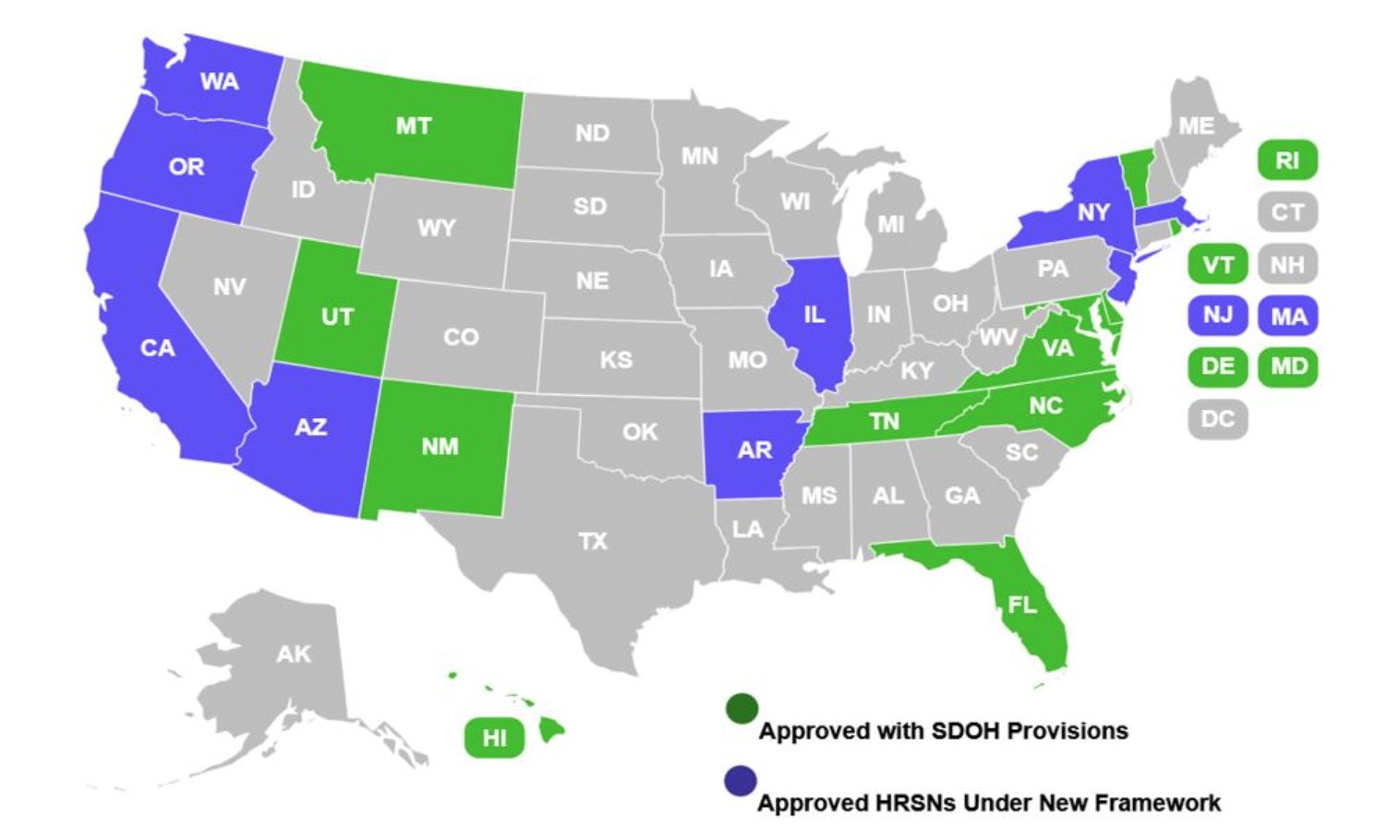

The imperative to partner up is even stronger if your food bank operates in one of the states that is exploring new ways of addressing healthcare through a Medicaid 1115 demonstration project (see illustration, top). “If you’re in one of those states, you need to be talking to your Medicaid agency, because they’re pulling down Medicaid dollars from the federal government to address health related social needs and, almost universally, that includes food security,” Quinn said. “So let’s make sure you’re a part of that.”

Food is Medicine is based on the understanding that a society’s health is dependent not just on medical interventions, but also a variety of environmental factors, like whether people have access to healthy food, housing, and clean air. According to Quinn, the United States spends much less on these social aspects of health than do other countries. Medicaid 1115 projects are a way to channel more funding into these non-medical inputs to health. “What we need to be doing is investing in the social care that you all are providing,” Quinn noted.

Even without Medicaid 1115 waivers, there are ways for hunger relief agencies to tap funding from the healthcare system to pay for nutritious food. Non-profit hospitals, for example, are obligated to invest in the community to retain their tax-exempt status, and many decide to funnel that money toward healthy food. Even for-profit healthcare systems are motivated to invest in nutritious food in the interest of preventing more costly hospital stays down the line.

Healthcare payers have choices about who they partner with to address those social aspects of care. Often, those that work with hospitals over a large geographic area will seek out equally large providers of nutrition-related services for Food is Medicine, leaving local nonprofits out of the picture (Food Bank News wrote about that risk here). “If we’re not watching, we’re not going to have a piece of this at all,” Quinn noted.

So what can local nonprofits do about it? Quinn advised putting in safeguards to ensure that local food systems still benefit even when large healthcare systems contract with for-profit businesses for Food is Medicine, such as by ensuring that a percentage of all food sourcing goes to local food systems (see our article here for an overview of such for-profit businesses). “Your role at the local and state level is to put some guardrails on this,” Quinn said. “Let’s make sure this is improving our local food ecosystem, because it can very easily go another way.”

Quinn warned that community based organizations (CBOs) like food banks run the risk of providing nutrition-related services without getting adequately compensated. “You have to make sure that you know what it costs to provide what you’re being asked to provide, and that you are effectively negotiating for that,” she said. “Require payers to invest in what CBOs need in order to participate in Food is Medicine.” – Chris Costanzo

The illustration, top, is provided by Health Management Associates.

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News