Miles-long lines at food banks during Covid highlighted just how easily families may slip into food insecurity, despite the ongoing efforts of food banks over the past 50 years to distribute food.

Even before Covid exposed the precarious nature of many families’ food budgets, hunger relief organizations were beginning to realize they needed to do more than distribute food to end food insecurity. Now, preliminary results from a survey of nearly 250 hunger-relief organizations underscore that growing realization.

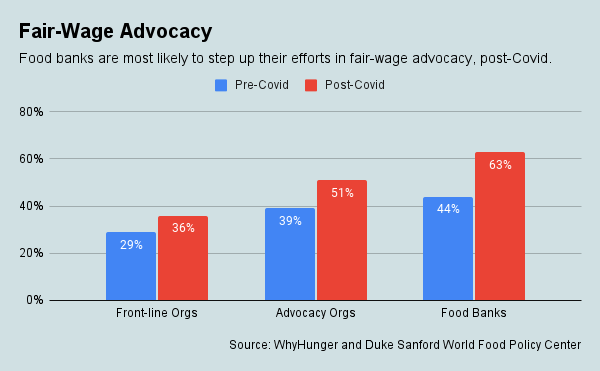

One of the more significant findings of the survey of 242 food banks, front-line food providers and anti-hunger advocates by WhyHunger and the Duke Sanford World Food Policy Center is that organizations plan to spend more time on advocacy work after the pandemic than they did before.

“Covid amplified the idea that food distribution alone is not ever going to end hunger,” said Alison Cohen, Senior Director of Programs at WhyHunger.

[Food Bank News identified 21 food banks (of the 100 largest) that excel in advocacy. See the full list in our Advocacy Honor Roll.]

Food banks, in particular, are more attuned to the need to advocate for fair wages, with 63% of them saying they would spend time on that post-Covid, compared to 44% that did pre-Covid. Compared to front-line organizations (36%) and anti-hunger advocates (51%), food banks are the most interested in working in this area post-Covid.

The protests over racial inequity that erupted last summer also seemed to bring into focus the impact of food-system inequities on food insecurity. Organizations were most likely (80%) to cite inequitable access to healthy food as a weakness of the current food system. In addition, 61% cited structural racism as a food-system problem.

By a small margin, food banks indicated that they were more likely than other types of organizations to address structural racism by shifting their programming (53%), compared to advocacy organizations (52%) and front-line community groups (35%).

Devoting resources toward advocacy has always been top of mind at Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard, a community food resource center that was founded in 1998 by people who needed food assistance themselves.

The Bloomington, Ind.-based organization has found that communicating the importance of advocacy was necessary to overcome ingrained views about the emergency food system. “Our advocacy program was a response to and an acknowledgement that emergency food alone cannot solve the problem and in fact is perpetuating it,” said Amanda Nickey, President and CEO at Mother Hubbard’s. “Changing the way people think about emergency food was part of it in the beginning.”

Advocacy has now evolved to being a priority in Mother Hubbard’s budget, with one full time person (out of eight) devoted to it, as well as additional staff who contribute. Among the activities are monthly dinners (in non-Covid times) designed to foster community among clients and offer opportunities for people with lived experience to engage in legislative or other work, often related to wages, housing or healthcare.

The results of the WhyHunger/Duke survey indicate that more hunger relief organizations may be adopting Mother Hubbard’s approach. “Finally the community is seeing all the things that we knew,” Nickey said. “It’s an opportunity to change public perception and the narrative.” — Chris Costanzo

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News