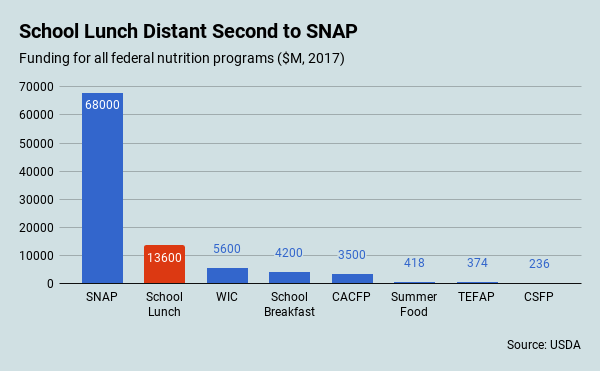

The National School Lunch Program is the largest of the school-based food-assistance programs, receiving $13.6 billion in federal dollars in 2017, more than three times the amount as the School Breakfast Program. It is available in 95% of the nation’s schools, and served about 30 million children every day in 2017, about 60% of the almost 51 million enrolled in public schools. In recent years, the program has made strides in serving healthier food to more kids.

While the program seeks to address the needs of low-income kids, any child attending a participating school can take part in school lunch. Kids pay different prices, however, depending on their family income. Nearly one-third (8 million) of the students who participated in 2017 paid full price. Another two-thirds (20 million) received their lunches for free, while two million paid the reduced price of 40 cents. The government reimburses school districts at a sliding scale for each meal they serve: $3.23 for every free meal served; $2.83 for every reduced price meal, and 31 cents for every fully paid meal (in the 2017-2018 school year). Participating school districts strive to balance their cost of serving the meals against the amount of federal reimbursement they receive.

In 2010, the USDA tested this balance by imposing higher nutritional standards on school food. While the concern when National School Lunch was started during the Great Depression was to provide enough calories to support kids’ healthy growth, the goal in recent years has shifted toward improving food quality and lowering calorie counts to prevent obesity. The 2010 Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act addressed those issues by adding minimum required servings of fruits, vegetables and whole grains, and putting limits on total calories and sodium.

Following some fits and starts, the sweeping effort to point kids down a path toward healthier eating is making progress. Not surprisingly, kids initially balked at being strong-armed into eating healthier food, and reports flourished about fruits and vegetables being tossed into the trash. Some school districts also decried the higher costs of serving healthy food, which they said was aggravated by the risk of losing reimbursement revenue from kids who chose to stop buying school lunch.

The USDA has maintained the success of Healthy Hunger-Free Kids, pointing to increased consumption of fruits and vegetables, and exposure to healthy food, as well as greater participation and revenue, with no major changes in food waste. Even so, important factions like the School Nutrition Association continue to push for adjustments that would ease some of the nutrition requirements, which it claims lead to reduced student participation, higher costs and wasted food. In fact, participation in National School Lunch has declined in recent years, by 1% from 2016 and by 6% from 2011, according to the USDA.

Another major change to National School Lunch came during the 2014-2015 school year when a provision that broadens eligibility for no-cost meals was rolled out nationwide, with the aim of boosting the number of kids taking part in school lunch. Under the Community Eligibility Provision, any school with at least 40% of students qualifying for free or reduced price meals can offer free meals to all of its students, without requiring applications. The program removes the stigma of a separate meal category for low-income kids, while streamlining cafeteria service and reducing paperwork. During the 2016-2017 school year, the third year in which CEP was available nationally, the number of children participating in CEP rose to nearly 10 million, according to Food Research & Action Center. Despite this strong growth, about half of eligible school districts are not yet participating in the CEP program.

Looking forward, school districts and health advocates are expected to continue to work toward finding the right balance between nutritional quality, taste and cost for a demanding clientele.