What’s the best way to strengthen SNAP?

The sprawling program, which cost $113 billion in 2021 – nearly double the $60 billion spent in pre-pandemic 2019 – is guided by a vast set of rules and requirements. These stipulations ultimately dictate how many people are served by the program and how well.

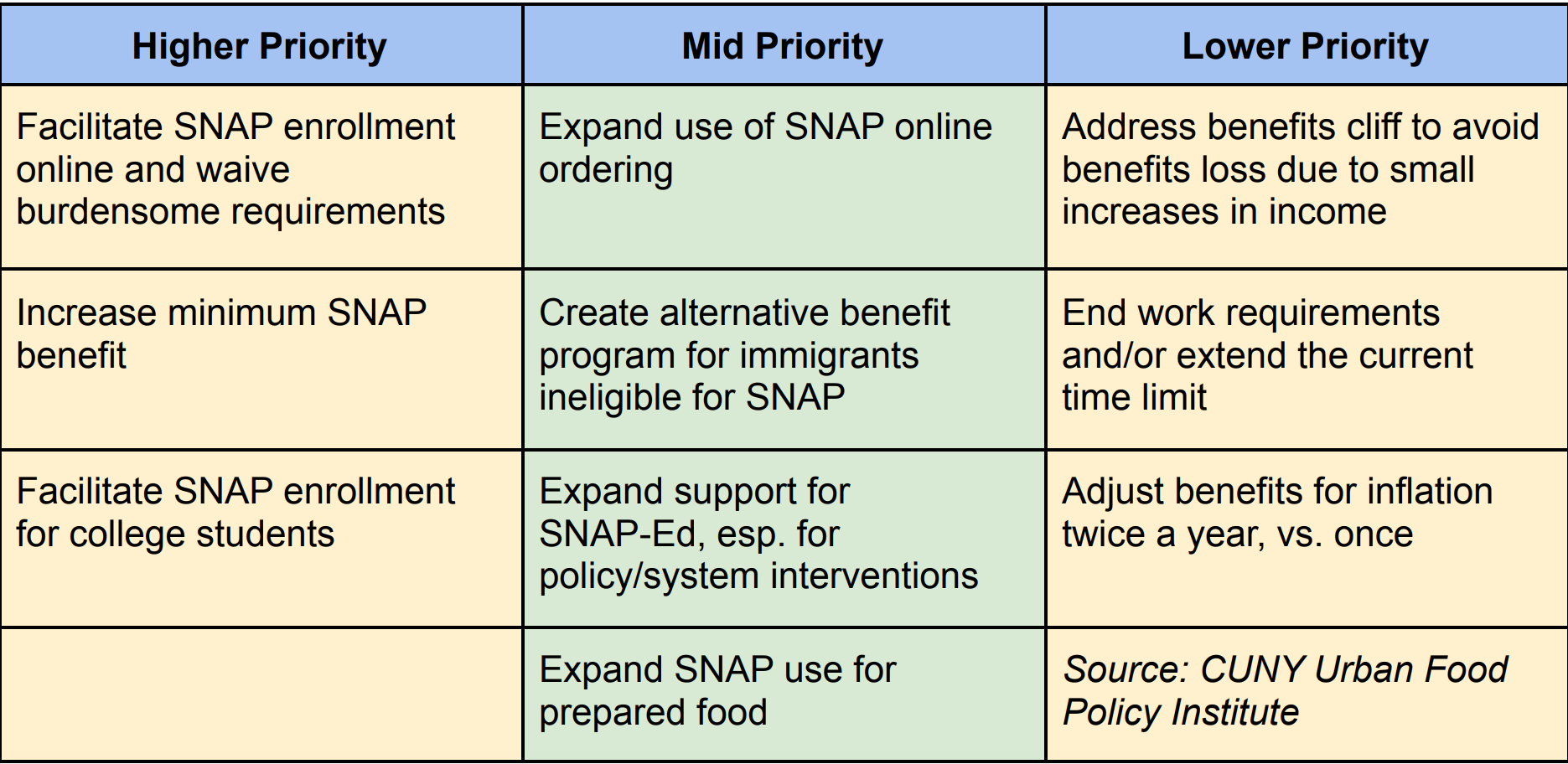

The Urban Food Policy Institute at City University of New York wanted to know how advocates should focus their attention when it comes to lobbying for rule changes that would lead to a stronger SNAP. So it identified 10 possible actions and invited about 50 participant-advocates at a recent virtual forum to rank the actions by both their importance and feasibility. The results serve as a loose blueprint for people who would like to see improvements to SNAP, and would welcome guidance on where to begin.

Highest on the Institute’s unofficial list of priorities is to make it easier to apply and re-certify for SNAP. One of the biggest lessons of the pandemic was the realization that enrollments could be handled online or even over the phone, freeing people from the burden of having to show up in person. While the pandemic made the changes necessary, they may not remain permanent.

“Simplifying the recertification and enrollment process increases the number of people and helps to reach more of the people you need to reach,” said Sergio Mata-Cisneros, Domestic Policy Analyst at Bread for the World, speaking on the virtual forum.

Alongside online enrollment is getting rid of burdensome application requirements. One such burden is a lifetime ban on SNAP for convicted drug felons, 90% of whom experience food insecurity upon their return to society. While many states have modified or removed the ban, legislation currently in Congress would eliminate the ban at the federal level. Another piece of legislation, the Lift the Bar Act, would get rid of a five-year waiting period to access benefits for immigrants who are lawfully present, permanent residents.

“These are immediate steps the federal government could take,” Mata-Cisneros said.

Also among the top three initiatives on the Institute’s informal list is to make additional increases to the minimum SNAP benefit. There is already some momentum in this direction with the introduction over the summer of the Closing the Meal Gap Act, which would increase the baseline for SNAP benefits by 30%, eliminate certain barriers to access, and expand the benefits to U.S. territories.

Rounding out the top three priorities is facilitating SNAP enrollment for college students. The national nonprofit Swipe Out Hunger is making progress in this area through its Hunger Free Campus legislation, which has been passed in five states and introduced in nine others.

Though only about 4% of SNAP households currently use their SNAP benefits online, online-ordering via SNAP (fourth on the Institute’s unofficial priority list) has “immense potential,” said Sameer M. Siddiqi, PhD, Associate Policy Researcher, RAND Corp., on the virtual forum. While delivery fees for online orders are a cause for concern, those could be reduced by setting up centralized hubs where people could pick up food or could be eliminated altogether, Siddiqi said. Another positive step would be to have more grocery stores participating in online ordering in the communities where more SNAP recipients live, he said.

SNAP Education (a mid-level priority) could have more impact if people viewed it as useful beyond just supporting nutrition education. Many people don’t realize SNAP-Ed can also be used to advance impactful work related to policy and systems interventions, Siddiqi said. Examples include improving the quality of food in schools and cafeterias and even working with local, SNAP-accepting retailers to stock healthier food. Though currently “underutilized,” SNAP-Ed is a “potentially transformative complement to SNAP,” Siddiqi noted.

Given all the competing priorities related to SNAP, it’s useful to take the long view. Jan Poppendieck, PhD, a self-proclaimed “SNAP watcher for half a century” and the author of Sweet Charity, offered the encouraging viewpoint on the virtual forum that “advocacy works. It makes a huge difference. We have enormous records of success both in legislating improvements and defending existing benefits.”

Poppendieck, who is also Senior Faculty Fellow at CUNY’s Urban Food Policy Institute and Professor Emerita of Sociology, added that advocacy can take a long time to show results. When food stamps first became available, for example, program participants were required to purchase their food stamps to receive an amount of food that exceeded the purchase price. Eliminating the purchase barrier was advocates’ first priority and took an entire decade to become law. “Persistence pays off,” Poppendieck said. “Don’t give up.” – Chris Costanzo

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News