The Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona (CFB) is one of the oldest and most respected food banks in America. It is a widely recognized leader not simply in providing hunger relief but in attacking the root causes of hunger and poverty through community development, education, and advocacy.

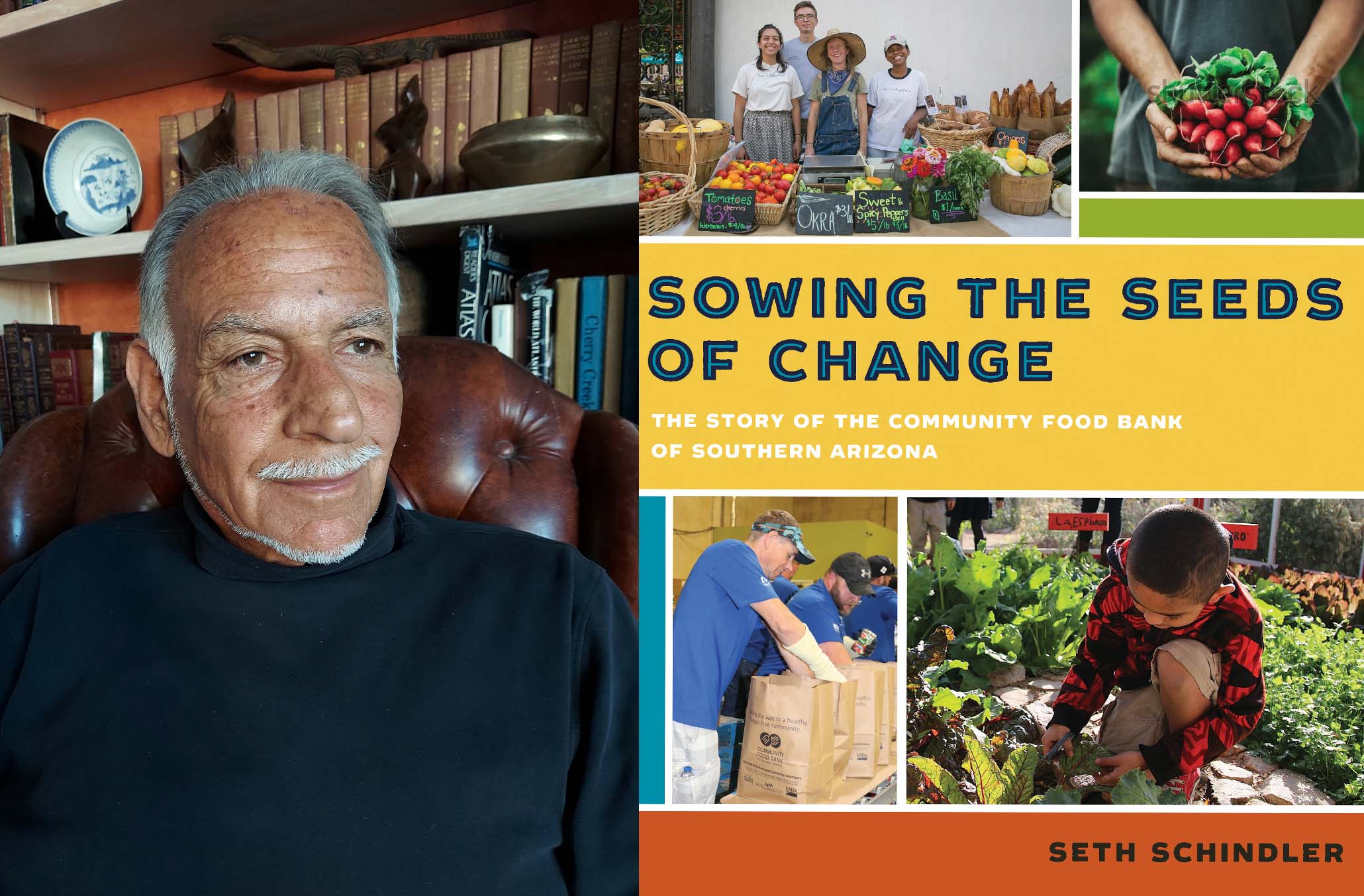

In Sowing the Seeds of Change, a recently published book by The University of Arizona Press, author Seth Schindler tells the story of this remarkable organization’s sustained, compassionate response to food insecurity. The success of the CFB demonstrates that the war against hunger, however difficult, is winnable. Schindler answers five questions about this new book, one of the first works to chronicle the history of a food bank.

What drew you to the story of the CFB?

I realized that the story of the CFB was much bigger, more complex and intriguing than I originally thought. I learned about the enormity of the problem of food insecurity in the U.S. and in Arizona, which shocked me; then the surprising massive scale and diversity of the CFB’s operations throughout southern Arizona; and finally its reputation as a national leader and innovator in the food bank movement, admired for its groundbreaking work in attacking the root causes of food insecurity. The zeal of staff, volunteers, and other participants in the CFB’s programs also impressed me. Finally, conversations with Charles “Punch” Woods, the CFB’s leader during the first decades of its evolution into the extraordinary organization we know today, inspired me, convincing me that this was an engaging original story that needed to be told.

To my knowledge, there was no book about a food bank in the U.S. I hope that by writing one, I’ve helped illuminate the organizations like CFB that do such critical work!

How did the CFB get started?

The founders’ mission was an ambitious one—to end hunger in Tucson. They believed that the Food Stamp Program was poorly managed, that too many food-insecure people fell through the cracks, and that too much food was going to waste in the city. Mark Homan, Barry Corey, and Dan Duncan sensed that there had to be a more efficient way to distribute food and reach more of the hungry, as well as make better use of salvaged food.

Their strategy was two-fold: to distribute emergency food boxes through Tucson’s many nonprofits—both welfare and faith-based agencies—already serving the hungry; secondly, to make it as easy for individuals and commercial operators to donate the food as to throw it out.

The CFB began in 1976 in a tiny primitive warehouse in South Tucson, with one employee, director Dan Duncan, one volunteer, Arnie Salverson, one delivery truck donated by a local business, a few boxes of canned food, and a $7,000 grant from the city. Yet in the first year alone the CFB distributed 10,544 emergency food boxes and 80,000 pounds of salvaged food! This clearly surprised the founders who initially underestimated the demand for their services. Those in need, they discovered, included not just the homeless and the unemployed, but the underemployed, the working poor struggling to put food on the table for their families. In southern Arizona, about 1 in 6 residents, and 1 in 4 children, experience food insecurity.

Today, operating out of its Tucson headquarters, the enormous Punch Woods Multi-Service Center, and its several branches throughout southern Arizona, with the help of thousands of staff and volunteers, and an annual budget exceeding 125 million dollars, the CFB distributes tons of food through 375 partner agencies to 200,000 food-insecure people.

This story of the CFB’s incredible growth to meet an ever-increasing need over the past half century is at the heart of Sowing the Seeds of Change.

How did your work as an anthropologist shape your research for this book?

Apart from archival research, in-depth interviews with staff, volunteers, donors, clients, and other CFB participants, activities that anthropologists call “participant observation” became essential as the book progressed. Getting out into the field to directly study CFB operations, sometimes working along with staff and volunteers, such as at warehouses, pantries, soup kitchens and the CFB’s community farm, put me in touch with what was really happening in their programs. These traditional techniques used by ethnographers helped, I believe, distinguish this book from conventional institutional histories.

Early on I also realized I wanted the book to reach a wide audience, including the CFB’s clients, and to develop a writing style and a book design—incorporating, for example, substantial graphic material—that would more easily help achieve that goal. I would then also take advantage of my experience as a storyteller and in writing about a variety of topics for the general reader.

Perhaps the most important feature of the book, and my biggest breakthrough in developing it, was the decision to include profiles of a diverse group of CFB participants through the years, and not just the organization’s leaders. These reveal their thoughts about their roles, presented in their own words. In recent years, anthropologists have been criticized rightly for not doing this adequately when researching and writing about the people and cultures they study. Sowing the Seeds of Change contains dozens of sidebar quotes from those individuals who have created the CFB’s culture of caring, sharing and innovating, and contributed to the organization’s success. Their voices personalize the story of the organization and help to distinguish the publication by adding a crucial human dimension not typically found in history books.

What surprised you the most during your research?

I have to say I was shocked by several things I learned in the process of researching this book—many decidedly positive but some alarmingly negative and hard to comprehend. How do you explain, for example, that in the U.S., the richest country in the world, there are over 35 million food-insecure people?

Unfortunately, I never found an easy answer to this paradox. What I did discover, however, is that Tucson is filled with people who care deeply about the plight of the hungry among us, and who help them routinely. In this respect, the passion of CFB staff, volunteers and others in the community, directed at helping the less fortunate, continues to amaze and lift me.

I also discovered that the CFB today is far more than a hunger-relief organization, a fact that many in Tucson do not know, and one I emphasize in the second half of the book called “It Takes More Than Food.” The mission today is not just to “shorten the food line” but ultimately to eliminate it through education, community development and advocacy. Several hunger-prevention programs have been developed in recent years with this goal in mind, all directed at empowering the poor and breaking the cycle of poverty that is the cause of food insecurity, especially among the most vulnerable groups—children and seniors.

The CFB, for example, has developed its own demonstration/learning garden; classes in cooking and healthy eating for both adults and school children; a community farm with plots for clients; two farmers’ markets; a culinary training program aimed at providing careers for the unemployed and underemployed; and the Gabrielle Giffords Resource Center that offers social services to clients. It has also drastically increased the amount of fresh produce in its food boxes, including ones designed for seniors and to combat diet-related disease.

In 2018, Feeding America named the CFB “Food Bank of the Year” in recognition of its achievements in serving its community. The CFB’s success serves as a model for other nonprofits to follow no matter their mission.

Why are volunteers so essential at the CFB?

Today there are over 6000 volunteers working with the CFB’s staff of about 140. Such a large number is essential because of the CFB’s diverse activities and ever-expanding programming in a very large service area—23,000 square miles. Distributing food to over 200,000 people in several counties is no easy task, but that’s not all the CFB’s volunteers help with. They contribute importantly, for example, at the CFB’s farmers’ markets, Caridad Community Kitchen, Nuestra Tierra Learning Garden, Las Milpitas Community Farm, the Ambassador Program, the Produce Rescue Program, and in its many food drives.

Volunteers are the heart and soul of most nonprofits, and the CFB is no exception. However, based on what I observed conducting fieldwork, the CFB’s volunteers are a truly exceptional group—highly dedicated and competent. This take on the CFB’s volunteer work force was corroborated by the food bank experts I interviewed who also believe there’s always been something special about the Tucson community and its compassionate residents who work selflessly for the common good. In this respect, it should be pointed out that Tucson and the southern Arizona region generally does have an advantage over most other food banks in the US. The CFB can draw on this area’s very large retirement community of seniors with the leisure time to volunteer.

Nevertheless, I believe that the success of the CFB’s volunteer work force can also be explained in light of the CFB’s legendary, distinctive culture of caring, sharing and innovating, which is contagious. This culture, marked by the spirit of egalitarianism, was first shaped by its charismatic leader, Charles “Punch” Woods who guided the CFB through its most challenging early phase of evolution, and it remains intact and vital today. It doesn’t hurt either that the CFB continues to offer volunteers well-run programs in which to work and a friendly, family-like atmosphere where respect for others, and clients especially, is the name of the game. Finally, the nature of this volunteer work itself–whether in the warehouse, the pantry or the garden –is innately very appealing.

What can be more satisfying than seeing the smiles on the faces of the people you help?

Seth Schindler is an anthropologist and former NEH Research Fellow and Weatherhead Resident Scholar. He has contributed articles to the American Anthropologist and The Encyclopedia of Anthropology, among many others.

To learn more and/or to purchase Sowing the Seeds of Change, click here.