When Susannah Morgan started working in hunger relief 26 years ago, she believed that getting more food to more people was the answer to eliminating hunger. Now she understands the problem of hunger differently – and it’s changing everything about the way she approaches her job as CEO of Oregon Food Bank.

Like many of her peers, Morgan came to realize that people are not hungry because of a lack of food, but because of inequities built into society that prevent people from obtaining a quality standard of living. To many, realizing the depth and breadth of the hunger problem is overwhelming and draining.

But to Morgan, the ability to identify the problem made it manageable. “The more I’ve thought about it, the more I’ve come to understand that these results are coming out of systems that we designed,” she said. “To me that means that if we made them, we can make them differently, and that means a solution is actually possible.”

Oregon Food Bank’s strategic direction through 2029 reflects Morgan’s clear-eyed embrace of the broad scope of the hunger problem and the steps necessary to tackle it. It calls for the food bank to take a lead not just in food distribution, but also in community-building, power-sharing, wide-reaching advocacy and civic engagement.

Morgan realizes that pushing systemic change will not be easy. “It will take a couple of generations of serious work,” she said. Nor will it enable the food bank to sidestep its original purpose of distributing food. “Because it’s evil not to,” Morgan noted.

While food banks have been built up as logistics organizations for feeding the hungry, they actually are well-suited for the job of pushing societal change, according to Morgan. Between its donors, volunteers and those it serves at its 21 regional food banks and 1,400 food assistance sites, Oregon Food Bank already touches about 1 million people – or one-quarter of the state’s population.

“We’re already a community,” Morgan pointed out. “And we’re also a political power if we can be targeted and activated.”

In fact, the community is already activated. In Oregon’s most recent legislative session, for example, the food bank was part of a coalition that helped secure overtime pay for farm workers who work more than 40 hours a week, a first for more than 70,000 people in the state.

It’s one effort among many that are necessary. “There’s no single thing, there’s no silver bullet,” Morgan said. “But piece by piece we can replace systems that tolerate hunger with those that don’t.”

The “incredible strength” of the logistics infrastructure that food banks have built up offers a starting point for community organizing, Morgan said. Food banks are fairly unique in the level of interaction they have with such a broad range of people who have lived experience of hunger or care about those who do. “We can leverage this service infrastructure to do organizing,” Morgan said.

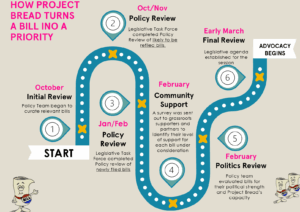

Oregon Food Bank now has a database of over 15,000 people who have taken some sort of civic engagement action over the last few years, all of whom can be targeted based on the district they live in and the topic at hand. Recently, for example, when a piece of legislation was stuck in committee, the food bank was able to identify and reach out to seven people who had interest and sway in the issue. The next day, the legislation moved out of committee. “Sometimes you need oodles of people and sometimes you need just the right one,” Morgan noted.

There was a time when Morgan thought that hunger could be ended through creative programming that targeted individual families. In fact, programs like nutrition education and financial literacy have taken hold in recent years, and made a difference for those who participate. But these programs can never reach enough people. “You can never get to scale,” Morgan said. “Only at the government level do you get to scale.”

In addition to seeking out far-reaching, systemic-level change, Morgan believes strongly that the people most impacted by the change have to be at the center of it. That tenet led to the launch in 2021 of the food bank’s 15-member Policy Leadership Council, a governing body made up of people who have experienced food insecuirty and/or other forms of oppression.

The Council is tasked with taking the lead on identifying the public policy issues the food bank should focus on and how to address them. Already, the Council has led the food bank to focus on legislation related to over-policing, which would not normally have been on the food bank’s radar screen.

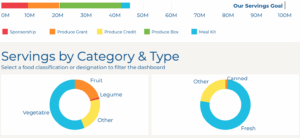

The desire for systemic change led by those most impacted by hunger is now the basis of Oregon Food Bank’s long-term strategy. In the first of three concrete steps, the food bank plans to onboard more distribution sites run by groups that disproportionately experience hunger, including communities of color, immigrants, migrant refugee groups and transgender communities. “If we can create solutions for those four groups, we’ll have solutions for all,” Morgan said, adding that the food bank received a $1 million grant from Feeding America to lean into that work.

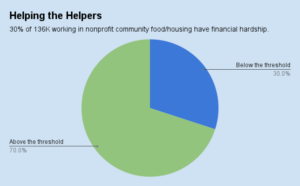

Secondly, the food bank is supporting BIPOC farmers, grocers and food producers through capacity grants, as well as through direct purchases amounting to about half a million dollars. Finally, it is “hiring community organizers like mad,” Morgan said. The plan is for about 15 hires over the next three years to build out community organizing to support systemic level change, Morgan said.

The goal is a more just and equitable society, with less hunger as a byproduct. “Our vision is to build communities that never go hungry,” Morgan said. “The only way we know how to accomplish this is to nurture and cultivate communities that will not tolerate hunger.” – Chris Costanzo

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News