Fundraising is a big part of any nonprofit’s work. But what happens when the relentless drive to get money and please donors comes at the expense of an organization’s core values?

That’s the question C. Nathan Harris posed to the Oregon Food Bank two years ago when he was interviewing for the position he holds today. As Director of Development, Harris has spearheaded a transformation of how the organization’s 30-person development team raises funds. In place of money, the food bank has decided to center love.

Unconventional? Yes. But the food bank maintains that traditional money-focused philanthropy has too many characteristics that borrow from white supremacist and capitalist paradigms. “It is my belief that an orientation to financial outcomes in the work of philanthropic development is a gateway to harm,” Harris said.

Major problems in nonprofit fundraising point to that harm, Harris said, including high staff turnover and reports of sexual harassment. Meanwhile, donors report feeling relentlessly targeted for money. Diversity issues include the fact that fewer than 10% of development professionals are people of color and 61% of minority-led groups have a tougher time raising money.

In the context of food banking, many food banks are likely familiar with the type of conundrum presented by the corporate donor that wants to do a food drive because staff enjoys it, even though the resulting canned food may not meet the nutritional needs of pantry clients. Food banks hesitate to turn such donations down, underscoring the transactional nature of relationships.

Under its new approach, Oregon Food Bank is instead reaching for donor interactions that demonstrate care, respect, and putting clients at the center. It’s an orientation that requires it to replace traditional fundraising metrics with new ones less centered on money.

“It is a very difficult thing to measure, because we’re talking about changing hearts and minds, we’re talking about engaging tens of thousands of donors differently in the work, including extending opportunities for them to engage civically,” Harris said.

Despite the difficulties, the development team has gone the distance in terms of defining what love means in the context of their jobs. Among the tools it has created are assessments for analyzing development staff and donors, and it plans to gather input from the rest of the food bank’s staff and board on a broad set of indicators that will help it track progress over time.

Some of the current metrics for tracking love include: My work is aligned with my purpose at this time in my life; When something is not working within my team, I speak up; I understand and help advance the political journeys of supporters; I see our supporters as part of a larger community making sacrifices and sharing value; and OFB clients show they love us with their advocacy voice and power.

Prioritizing love and equity has resulted in more direct messaging about the root causes of hunger. Last year, for example, Oregon Food Bank sent out a direct mailer that referenced systemic racism. The overall response was positive, with only two donors calling to ask to be removed from the mailing list.

“We’ve found that risk to be rewarding in that it has given us the opportunity to understand that our community is truly with us,” Harris said. “I think our donors are so much more with us than not.”

De-centering money has also meant prioritizing staff health and safety. Traditionally, development staff have been encouraged to take meetings at donors’ homes, putting employees in vulnerable positions. Now the team is establishing a planning template to help staffers prepare for such meetings and ensure they are safe.

“Members of the team have felt a sense of relief in orienting their work to transformational and regenerative relationship building, rather than to money,” Harris said.

The development team has also started thinking about going after funding in new ways. The goal is to “reposition Oregon Food Bank not as a gatekeeper between funding and partners, but as a connector…[so] that we think twice before applying for a particular grant that might be better for a community-based organization that is smaller,” he said.

Importantly, the shift toward centering love does not mean that financial outcomes don’t matter. In a blog post, the food bank clarified that it continues to have financial goals. The difference is that the development team will not be evaluated by them. “Whether or not we reach our financial goals, we will be held accountable to the performance evaluation metrics we’ve designed within a framework of equity and love,” said the blog post.

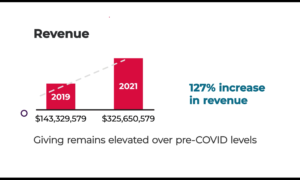

In fact, the food bank has more than doubled the size of its donor base in the last year. Harris isn’t sure if it has to do with being “far bolder in messaging and authenticity than ever before,” or growing awareness of food insecurity amid the pandemic, but it has been encouraging nonetheless. The team is also diversifying staff and its donor base.

Roey Thorpe, a Portland, Ore.-based strategy consultant to nonprofits, calls the initiative a bold revisioning. “It seems to be bringing much more alignment between the actual work of the organization and its values in all parts of the organization, including fundraising,” she said.

The traditional nonprofit model gives donors an outsized influence on programming and can sideline the communities being served, Thorpe added. “I’ve witnessed plenty of times when the most effective or most ethical approach is called into question by leaders who fear the impact it will have on the bottom line,” she said. “This approach holds so much hope for staff, but also for donors, because there is an opportunity to be seen and engaged with in ways that are deeper and go beyond monetary considerations.”

Making such a dramatic shift amid the pandemic has not necessarily been easy on staff at the food bank.

While many people felt instant relief that the problems with fundraising were finally going to be addressed, some were skeptical and even worried that failure would mean they would lose their job – or that the community they serve will go hungry. Harris said he wishes he could have put them more at ease with the process.

“This is all a massive experiment,” he said. “Some aspects of our change process could have been stronger, but the initiative occurred during the pandemic, during uprisings against anti-Black murder and violence, during wildfires raging throughout our region. And at the end of the day, I’m really proud.” — Ambreen Ali

Ambreen Ali is a freelance writer and editor based in New Jersey. She was formerly an editor at SmartBrief and a congressional reporter at CQ Roll Call in Washington, D.C.

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News