About 200 pantries in New York City have shortened wait times and boosted dignity by letting clients reserve times to pick up their food. Now the maker of the service, Plentiful, is seeking to work with food banks across the country to help bring the low-cost reservation system to other pantry networks.

It turns out pantry users are just as eager to take advantage of reservations as those who use OpenTable-type reservation systems to dine out on local eats. Having a reservation means not having to wait as long, often outside in the elements. Clients also benefit from quicker electronic check-ins, being able to look up the locations and hours of pantries, and getting reminders of their appointments.

Just as important is the data generated on the backend, which offers unparalleled insight into how clients utilize pantries. Plentiful’s system asks for a limited amount of client information, including zip code and household size, and uses it to answer big-picture questions such as how how far clients travel for pantries, how many they go to and how frequently.

“We’re not slicing and dicing the data,” Bryan Moran, Client Adoption Lead at Plentiful said. “We’re providing holistic views of what’s happening in the network.”

Such views are valuable because pantry networks can be haphazard, with too much food going to pantries in some places and not enough food to others. Such was the case among the nearly 1,000 soup kitchens and pantries of New York City when the social service agencies behind Plentiful came together to better understand how emergency food was being distributed across the city.

The collaborative, started in 2015 by the Helmsley Charitable Trust and the New York City Mayor’s Office of Food Policy, discovered 18 underserved neighborhoods, with some receiving only one-quarter of the food they needed. The highly populous Lower East Side of Manhattan, for example, was found to be served by only two moderately sized pantries, Moran said, while other areas were overloaded with food.

By increasing pantry capacity and re-balancing distributions, the collaborative managed to send out an additional 15 million pounds of food, without actually purchasing any food. It identified more than 90 pantries in underserved areas and helped them install new refrigerators, freezers and shelving. In some areas, it opened brand new pantries.

Its work complete, the collaborative, which also included City Harvest, the United Way of New York City and two government agencies as partners, dissolved this summer. But Plentiful, viewed as a “moonshot” project within the collaborative, lives on, continuing to support reservations while collecting and sharing useful data. Now it wants to bring that capability to other regions. “We’re just starting to reach out,” Moran said. “We’re looking to grow this beyond New York City.”

Plentiful’s target market is food banks supporting networks of pantries. While Plentiful is free for New York City pantries, as per its agreement with the collaborative, pantries in other geographies would pay nominal fees. The current estimate is $7 per month per pantry, plus a separate fee of about half a cent per text message (or $10 for 1,000 messages). Pantries could also opt into a free version of the service that would put them on the map of available pantries and allow for electronic check-ins and data collection, but would not support reservations.

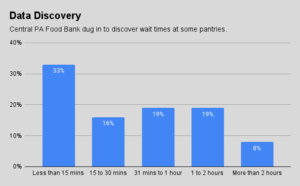

At many pantries, reservations are a game-changer, eliminating lines that form early in the morning for afternoon distributions. On average, Plentiful has found that wait times have been reduced from 1.5 hours to within 15 minutes of a 15-minute window, Moran said. “That’s a massive improvement,” he noted.

Food banks and pantries might also be interested in the direct conduit to clients that Plentiful offers. The system is optimized to facilitate communications: it works in nine different languages and has a text-message version so users don’t have to take up precious space on their phones by downloading an app. Users indicate their reservation choices via numbers, rather than writing out any words.

Through this trusted connection, food banks, pantries or other social agencies could easily conduct surveys of clients. Pantry clients are part of the so-called “unheard third” of the population that has no voice, but is also virtually impossible to reach because they are disconnected or uninterested in traditional survey methodologies or are afraid to participate. “There are many, many uses of survey data,” Moran noted, including getting feedback on pantry operations or finding out about additional needs.

Surveys, however, would be a sideshow to the real purpose of Plentiful, which revolves around giving pantries what they need. “They have a need to get rid of the line and communicate with clients,” Moran said.