Food banks might agree that they need to distribute healthy foods, but they haven’t always agreed on exactly which foods are healthy. Now a set of nutrition guidelines created specifically for the charitable food system is aiming to solve that problem.

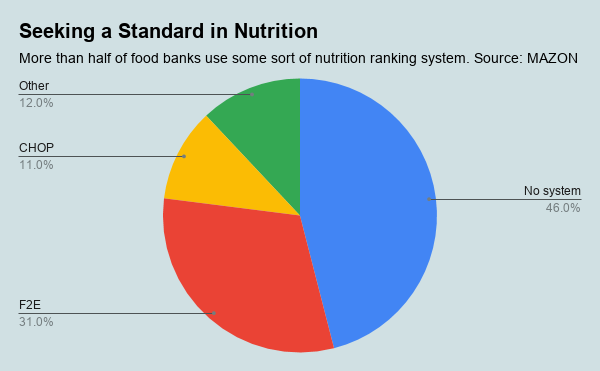

Just over half of food banks already use some kind of system to rank the food they distribute, but those systems do not always match up in terms of how they evaluate nutritional quality. The new guidelines seek to establish a standard framework for ranking nutrition, and make it easy for food banks to move toward the standard by evolving their existing system.

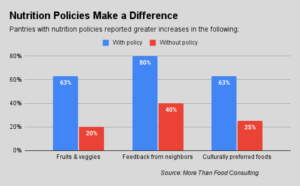

The hoped-for result is greater consistency in how food banks approach nutrition, and ultimately higher-quality foods being distributed and donated throughout the charitable food world. Food banks are increasingly interested in advancing the nutritional quality of the food they distribute as they seek to demonstrate their commitment to the health of the communities they serve.

“We have a responsibility in this work,” noted Dr. Katie Martin, Executive Director at the Institute for Hunger Research & Solutions at Conn.-based Foodshare and one of the architects of the guidelines. “It’s not just about the pounds. We have to pay attention to the nutritional quality of the food we’re providing.”

To create the new guidelines, the panel of experts convened by Healthy Eating Research, a unit of Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, took into account the particular complexities food banks face in moving toward healthier food, such as a reliance on donated food and volunteer help. Accordingly, the panel of 14, about half of them food-bank representatives, endeavored to make the guidelines both simple to understand and flexible to implement.

“They’re tailored to meet the unique needs and capacities of the charitable food system,” said Dr. Hilary Seligman, Senior Medical Advisor at Feeding America and an Associate Professor at the University of California-San Francisco.

The panelists confronted a mish-mash of contrary approaches to nutrition ranking as they began the project, with some systems (such as Feeding America’s Foods to Encourage, or F2E) placing food into yes-no categories and others (such as Supporting Wellness at Pantries, or SWAP) using tiers of green, yellow and red. The Choose Healthy Options Program (CHOP) calculates nutritional quality using a ratio of positive to negative nutrients, while SWAP identifies nutrients to limit. Systems also may rank products per 100 grams or per 100 calories, or by serving size.

“We needed common definitions,” Dr. Seligman said.

The panel met nine times by video conference through 2019 and into January 2020, making key decisions along the way. Among the first was to divide the food products into 11 categories (down from 31 for F2E, the most widely used of the existing ranking systems). Within the categories, foods are ranked based on their amounts of saturated fat, sodium and added sugar, all of which are easily located on the Nutrition Facts Label.

Foods get placed into one of three categories — choose often, choose sometimes or choose rarely — based on those levels of fat, salt or sugar. Foods with too much of any one of the three ingredients are automatically placed in the choose-rarely category. Dr. Seligman noted that no extra credit is given for fortification. “A sugary food doesn’t automatically become healthy with extra vitamins,” she said.

The panel also advised the visual aid of a red-yellow-green stoplight model to indicate how often foods should be chosen, making the guidance easy for clients to understand in any language. While food banks are not required to adopt the new framework, the panel is hoping Feeding America members will move toward it over the next five years. Toolkits to help food banks transition from F2E toward the new guidelines will become available in the fall.