A new food program introduced by the USDA draws on lessons learned from the Farmers to Families Food Box program to create an assistance program unlike any other in the hunger relief community.

The traditional aims of USDA food programs – nutrition assistance and food security – are not the overarching goals of the long-windedly named Local Food Purchasing Assistance Cooperative Agreement Program. Rather, the main goal is to spur economic development by building long-term pathways between disadvantaged farmers and underserved communities in need of food.

“This is uncharted territory,” said Elizabeth Atwell, Project Manager at Wallace Center, a food systems advocacy organization, during a strategy call.

The new program seeks to address weaknesses of the pandemic-era food box program, while also supporting the USDA’s goals of greater equity and inclusion. Importantly, the new program requires 100% of the food to come from local sources (particularly those that are socially disadvantaged), compared to only 20% for the Farmers to Families food box program. “Hopefully, that really helps local farmers and ranchers,” said Elizabeth Lober, Assistant to the Deputy Administrator of the Commodity Procurement Program, in a webinar.

The entities distributing the food also need to be local, and have connections in underserved communities. Under the Farmers to Families food box program, there were no such requirements and as a result, “there were many communities, especially in rural areas, that were not served by the program,” Lober noted.

The mechanism for making all these local connections happen will be state agencies and tribal governments – another difference from the Farmers to Families program, which tasked food-supply businesses with making decisions on how to source and distribute food. “We felt states could better handle ensuring that distribution was local and it was equitable,” Lober said.

With $400 million of funding over two years, the new program is far smaller than the Farmers to Families program, which had an allocation of up to $6 billion. Though more modest, the hope is that the local partnerships it funds will lead to long-term solutions that strengthen local food systems.

“The DNA of this program is all about supply-chain resiliency,” said Susan Schempf, Co-Director at Wallace Center.

The USDA has been explicit about the need to involve non-traditional partners in distributing food, including those that have not normally been part of food-bank distribution networks, said Kate Fitzgerald, Principal at Fitzgerald Canepa, on the strategy call. “There’s a super effort to make sure that regions that are often left out or were not served by Farmers to Families are included,” she said.

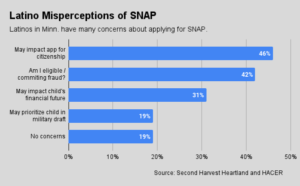

Those goals may well dovetail with burgeoning efforts by food banks seeking to develop new partnerships as they address inequities in food access. Good Shepherd Food Bank of Maine, for example, has been granting awards through its Community Redistribution Fund to support grassroots organizations led by and serving people of color. Second Harvest Heartland of Minnesota is making a $13.2 million investment in racial equity, which includes sourcing culturally connected food.

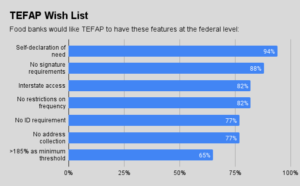

While food banks are increasingly interested in sourcing from local growers and producers, the reality is that local food can provide only a small portion of the total food needs of a food bank. The USDA has been seeking to make up for the loss of the Farmers to Families program by fortifying TEFAP with a nearly $500 million increase in base funding for fiscal year 2022, as well as a $500 million temporary boost to support fresh produce purchases. It also recently made $50 million in “reach and resiliency” grants available to support infrastructure investments in underserved areas.

Even so, the loss of the multi-billion dollar Farmers to Families program leaves a big gap. Food Bank of the Rockies, for example, has seen its food purchasing costs increase to nearly $1 million, almost triple the amount it spent in 2019, said Erin Pulling, President and CEO, largely because of the decrease in USDA-provided food through the Farmers to Families program. To make up for the loss of the Farmers to Families produce, Food Bank of the Rockies started a program called FRESH to spearhead purchases of produce delivered by the pallet-load to partner agencies. The food bank is also expanding its sourcing of culturally relevant food.

The flexibility built into the USDA’s new local-food purchasing program will allow for a wide variety of partnerships and outcomes, Schempf of Wallace Center said. The food box – a centerpiece of the Farmers to Families program – is not a requirement. Instead, a wider variety of food can be delivered in any one of a number of ways, and through a range of partners, including schools, senior centers, health care clinics and community organizations.

“All kinds of things can happen,” Schempf said. “It’s an opportunity for food banks and other partners to be at the table with state agencies to design programs that work at the local level.”

States and partners may want to expand innovative programs that are already underway. In Arizona, for example, a farm-to-food bank program run by the Arizona Food Bank Network could be scaled up to expand into other protein sources besides produce, said Jesse Gruner, PhD, RDN, Director of Community Innovation at Ariz.-based Pinnacle Prevention, speaking on the strategy call.

The Wallace Center is advising hunger relief agencies to reach out to their state governments to figure out which agency is taking the lead. Given the program’s emphasis on economic development and equity, it may not be the agriculture department. Next, agencies should create an inventory of all the programs already procuring local food and identify those that could grow sustainably.

Fitzgerald cautioned patience as overburdened, understaffed state agencies work through the novelty of the program. “This really is a different function that’s being asked of states,” she said. “It’s not only nutrition assistance, but also economic development.” – Chris Costanzo

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank NewsConnect with Us: