Taking cues from both Trader Joe’s and the food justice movement, Northwest Harvest of Seattle is opening a new food distribution center on June 24 that aims to offer a respectful, welcoming and even fun grocery shopping experience.

The name of the outlet — SODO Community Market (standing for Seattle’s South of Downtown neighborhood) — reflects Northwest Harvest’s intention to create a model that blurs the lines between shopping at the grocery store and getting food from a pantry. Sleek, modern and brightly lit, the market replaces the nearby Cherry Street Food Bank, which Northwest Harvest had operated for more than 35 years before being pushed out for real-estate development.

“We want to offer a dignified experience that is uplifting,” said Thomas Reynolds, who became CEO of Northwest Harvest in 2017. “We want it to be a shopping experience that people look forward to.”

Invoking a “humble Trader Joe’s,” Reynolds envisions clients filling their baskets with food, then “checking out” as if at a grocery, rather than signing in beforehand to receive their food. As at Trader Joe’s, workers will restock inventory during the day rather than at night to increase the number of small interactions between staffers and clients. Volunteers will receive training in how to be of service to clients, for example by passing along knowledge about available fruits and vegetables and how they can be prepared.

Long term, Reynolds’ dream is to evolve the market into a pay-as-you-go operation, where people pay either nothing, a little, or a lot. Shoppers with greater means could fund a supply of gift cards that others could use when needed, he said. The most powerful version of this vision is a movement in which grocery stores across the city routinely make food available to those who need it, rather than give away their excess to food banks, Reynolds said.

Besides food, the new space will offer meeting rooms. Like many organizations, Northwest Harvest views pantries as venues for a wide variety of community services (say, tax help or health screenings). Rather than sponsor such services, Northwest Harvest is looking to take a more of a backseat approach by making convening spaces available to local grassroots organizations, particularly those run by people of color. “It’s less about us sponsoring, which feels like a power dynamic, and more about opening the space and letting people add value,” Reynolds said.

The low-key approach is in keeping with a few things Reynolds learned during his tenure at CARE, where he directed anti-poverty programs across 95 countries. He found that projects could yield positive outcomes in the short term, but the most effective, sustainable advances came from local people who were passionate about making change in their community. In adopting this “less egocentric” approach, Northwest Harvest is acknowledging it doesn’t have all the ideas, Reynolds said. “We will find a way to join their work.”

Redefining the look and feel of the typical food pantry is just one way Northwest Harvest is seeking to challenge some of the basic precepts of food banking. It rejects, for example, the narrative that reducing food insecurity is a matter of logistics, requiring food to be rescued and redistributed. Rather, it sees racial inequity as a primary contributor. “For any sort of fundamental change in the U.S., we must confront issues of racial oppression,” Reynolds said.

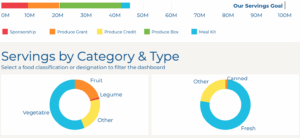

Casting food banking in a new light is requiring Northwest Harvest to also evaluate the success of its efforts in a new way. It is exploring various new metrics of success including:

- the maximum distance to affordable healthy food;

- the number of people with access to affordable food seven days a week;

- the percentage of people who believe hunger is an intolerable condition;

- the number of policies introduced or improved that help reduce food insecurity.

“We’re asking ourselves what we can do to actively counteract racial inequity,” Reynolds said.