The connection between poor mental health and food insecurity comes as no surprise to the people who run Chicago-based Lakeview Pantry.

While the pandemic has highlighted the link between food insecurity and mental health, Lakeview has been addressing the issue since as far back as 2017, when it began offering mental health services to clients. “Mental Wellness Services” are listed as an offering right next to “Get Food” at the top of its website.

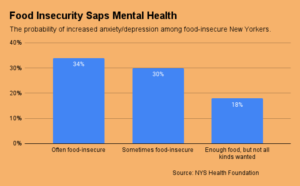

Given the severe impact of food insecurity on mental health, Lakeview’s explicit pairing seems right on target. Research studies released within the last year (here and here) underscore that low food security undermines mental health, with another study finding that food insecurity is associated with an approximate 250% higher risk of anxiety and depression – almost three-fold the impact of losing a job.

Lakeview noticed the mental health struggle of its food-insecure clients when it was offering wrap-around services such as SNAP outreach and rental assistance, but still saw people suffering emotionally. Referrals to outside mental-health providers did not cut it: services were expensive, even on a sliding scale, and often had wait lists as long as six to 12 months.

“When you’re in crisis, it’s hard to wait that long,” said Kellie O’Connell, Lakeview’s CEO. “We decided to intentionally offer mental health counseling by licensed clinical therapists free of charge. The difference of a few sessions of counseling can be really critical.”

Now, Lakeview is offering hour-long therapy sessions to about 100 clients a week. A team including four full-time licensed therapists and two interns provides therapy on par to what clients would otherwise pay hundreds of dollars for in private practice. “They’re able to access a service that seems like only certain parts of the population have access to,” said Jennie Hull, MA, LCPC, Chief Program Officer at Lakeview.

The therapists offer long-term, consistent care, improving upon the turnover often found at free clinics. Clients can also take advantage of bilingual therapists, couples therapy and group therapy. Recently, the pantry created a counseling group for queer people struggling with isolation and loneliness.

The therapists offer long-term, consistent care, improving upon the turnover often found at free clinics. Clients can also take advantage of bilingual therapists, couples therapy and group therapy. Recently, the pantry created a counseling group for queer people struggling with isolation and loneliness.

Lakeview built up its practice slowly, proving the concept by starting with interns and building off the case management services it already provided. Now the practice is supported mostly by a mix of private and government funding. “It’s a priority that we have,” Kellie said.

Lakeview’s mental health services capitalize on the sense of trust and safety it has already established with clients through its food distributions. “Having mental health services at a food pantry meets people where they’re at. It normalizes it,” O’Connell said. “Going to a clinic or a hospital can be scary, but this reduces the stigma.”

The services also reinforce the pantry’s intention to provide all of its services through a trauma-informed lens that emphasizes dignity and respect, and the need to take a holistic approach. “All organizations are thinking about how to serve the whole person,” Hull said.

Clients report improvements in their lives, including being able to secure housing, progressing in substance abuse treatment, and navigating career options. Eighty percent of clients strongly agreed (and 20% agreed) that their concerns have improved over their time in counseling and that their counselor understands their issues, Hull reported. “Just having someone there for you can have so much impact,” she noted.

By pairing mental health with food distribution, Lakeview is leading the way in answering a growing call for more innovative approaches to providing mental health services to vulnerable communities. Food builds the trust that makes it possible for clients to explore services they never before considered or perhaps never knew existed. “Meeting humans in a space they’re already going to makes it feel OK,” O’Connell said. – Chris Costanzo

CAPTION ABOVE: A social services space at Lakeview Pantry.

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News