Following a three-year pilot, the Kelly Center for Hunger Relief in El Paso, Texas, is moving full steam ahead on a program to help clients decrease their reliance on charitable food and move toward greater self-sufficiency. With many moving parts, the program represents a large commitment of resources and time — and it’s working.

“People are improving their lives,” said Warren E. Goodell, Executive Director.

Like many agencies, the Kelly Center for Hunger Relief has spent decades distributing food through its pantry, without seeing the need for food diminish. The program, known as FreshStart, is its attempt to move clients off the food line. “We’re trying to break the cycle of poverty,” Goodell said.

FreshStart builds upon food distribution by providing clients with numerous wrap-around services, along with goal-setting and coaching. Kelly Center for Hunger Relief received guidance in implementing and evaluating the solution from the More Than Food program based at Foodshare, the regional food bank in Bloomfield, Conn.

Now in its first full year of regular programming following a rigorous pilot, FreshStart expects to graduate 60 to 65 clients this year from the nine-month program. It continually adds new participants to the rolling-admissions program, graduating new groups every three to four months. It hopes to have 125 participants by July, up from 80 currently.

FreshStart begins with an assessment of the ability and willingness of candidates to make changes in their lives. In a tweak from the program’s early days, several volunteers who do intake for the food pantry have been trained to identify go-getters among the 2,500 people who come to the pantry every month, with the goal of better identifying those most able to succeed.

Once approved for the program, participants identify three goals they think will move them toward greater independence, such as getting a job or a better job, getting a degree or gaining citizenship. Unlike in the pilot when participants could choose goals such as losing weight or eating healthier, the goals must be related to substantially improving their livelihoods. Participants also fill out a survey on their perceived level of food insecurity and commit to doing volunteer work in the community.

Then begins the work of helping clients achieve their goals. Clients get assistance in the form of coaching, as well as referrals to other agencies. FreshStart employs five staff members, including a full-time director, who is a licensed master of social work; a part-time program coordinator; a part-time health and wellness coach; an unpaid intern, and a partly paid volunteer.

FreshStart has refined its approach to how it refers clients to additional services, after noticing in the early days that clients often did not follow through on the ones they were given. To overcome resistance, the center now strives to bring other community services into its building, offering them a temporary presence during food distributions, for example. “We’re trying to build collaboration versus just hand out referrals,” Goodell said. “Mostly that means getting their leadership over here to see what we’re doing. We’re trying to become a hub for the community.”

In addition to coaching and referrals, FreshStart offers a wide range of programming aimed at helping individuals build capacity to change their lives. Examples include financial literacy classes, self-esteem training, nutrition and exercise classes, English as a second language, and community meals. Participants also get twice as much food as regular pantry clients, giving them an incentive to stay with the program and ensuring that food scarcity does not distract them from meeting their goals.

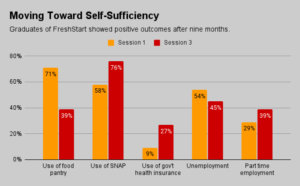

Now at the mid-point of the first full year of the program, Kelly Center for Hunger Relief is finding that 80% of clients are achieving their goals, or making significant progress toward them, Goodell said. This is in keeping with the findings of the pilot, which discovered that food insecurity decreased by 89% over nine months and that self-sufficiency scores increased significantly, by 7.6 points, over nine months. In essence, the pilot found that the program improved peoples’ lives in a statistically significant way and that the program is scalable, Goodell said.

While engaging in the work required to break the cycle of poverty is gratifying, it is also expensive. The budget for FreshStart this year is $225,000. Given the number of clients expected in the program by the end of the first year, the cost per client per month is expected to be $91. Goodell expects to cut that cost in half in Year 2, as the program expands into the community.

The long-term return on that investment to the community may be intuitively positive, but it’s not easily quantifiable, Goodell noted. Demonstrating that someone did not get diabetes because they are eating healthier, or that they are contributing to society by paying taxes through a job is hard to model. “We’re struggling with the ROI,” he said.

Even so, FreshStart has evolved from being a grant-funded experiment to being part and parcel of the organization, Goodell said. The original funder of the pilot, Paso del Norte Health Foundation, is currently funding only half of the program, with the remainder coming from other companies and foundations, including the Texas Methodist Foundation.

Recently, the Kelly Center for Hunger Relief changed its name from Kelly Memorial Food Pantry to reflect its larger focus on addressing the fundamental causes of poverty and hunger. “We’re maturing in terms of our ability to work with people in need,” Goodell said.