After months of making do with far fewer volunteer resources during the pandemic, hunger relief organizations are getting creative as they work to reinvigorate their volunteer ranks.

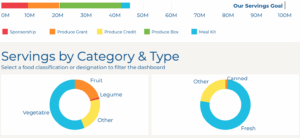

Some are finding value in relying on clients as volunteers. Others are finding ways to engage highly skilled workers for special projects. And a growing number are using software to help recruit and manage volunteers (see chart below), replacing manual tasks with more streamlined processes.

As one of only 11% of nonprofits nationwide earning recognition as a Service Enterprise from Points of Light for upholding high standards in volunteer management, Second Harvest Heartland’s approach is notable.

As one of only 11% of nonprofits nationwide earning recognition as a Service Enterprise from Points of Light for upholding high standards in volunteer management, Second Harvest Heartland’s approach is notable.

The Minneapolis, MN-based food bank divides its volunteer workforce into three categories that are delegated different tasks, collectively contributing to the singular goal of eradicating food insecurity, said Julie Greene, Director of Volunteer Engagement.

Most volunteers participate in recurring tasks like packaging bulk produce, sorting food, and delivering food boxes. Others function in ongoing support roles, in which they may make weekly food deliveries, help clients with SNAP applications, or do database support. The third category, known as pro-bono volunteers, consists of retired professionals or seasoned volunteers who undertake advisory roles to assist with the swift execution of high-end projects.

“We have some volunteers here who have been with us for 5 to 15 years. So, we are trying to integrate them into the team and be more of a member,” Greene said.

The food bank’s pro-bono program supplies professional services and expertise to special projects, such as data analysis, strategic planning, cost modeling, and marketing, allowing the food bank to affordably source assistance that would otherwise be difficult to obtain. In fiscal year 2020, pro bono volunteers contributed nearly 4,000 hours of work to about 40 different projects, delivering an estimated value of nearly $770,000 in professional consultation to 18 different Second Harvest Heartland teams.

The food bank now has a person fully dedicated to its pro-bono program. “This way we can hear from the volunteers. Where are you struggling as a team? Where do you have the capacity for more growth? Where do you not have a certain skill set? This way we can identify the area where we can bring on an expert to add that skill set or capacity,” Greene said.

At a food pantry chain based in Milwaukee, big value is coming from recruiting its clients as volunteers. At Friedens Community Ministries, almost 30% of the volunteer workforce are current or former clients of the pantry, or people who either know someone or have experienced food insecurity.

Sophia Torrijos, Executive Director at Friedens Community Ministries, said having an inclusive and diversified volunteer workforce makes clients feel more comfortable and welcome. “Ultimately, having members of the community throughout every aspect of our operation keeps us grounded to what the community needs,” Torrijos said. “It keeps us accountable for centering everything we do around dignity.”

Building a reliable volunteer workforce takes targeted nurturing and guidance, Torrijos said. “Every volunteer, regardless of their status and background, requires a different level of support. You have to meet them halfway,” she said.

Volunteers who have experienced food insecurity in the past or have prior experience assisting at the pantry might need little guidance. A group of students, however, might need a more comprehensive orientation.

For every intake of new volunteers, Friedens undertakes a robust process consisting of a debrief and a detailed orientation focusing not only on logistical tasks but also on making sure individuals are trauma-informed and “know how to treat people with dignity.”

While all of these approaches hold promise, food banks across the country are still feeling the ripple effects of the pandemic. “We are still trying to navigate the pandemic,” Greene said. “We are seeing volunteer groups return, but it’s hard to gauge. Sometimes we are expecting a group of 30 to 40 volunteers, but only half sign up. How do we navigate that day? Do we purchase more or less? Do we still run that shift or cancel the shift?”

Food logistics are being affected, too. Last month, on a Saturday shift, a truck loaded with potatoes did not show up at a site, leaving the volunteers with no task at hand. The shift had to be canceled.

Given ongoing challenges, the need for volunteers remains as high as ever.

According to Samantha Solberg, Communications Specialist at Second Harvest Heartland, Minnesota is expecting one of the hottest and “possibly one of the hungriest” summers in recent years, with rising gas prices and inflation only making it worse. In addition, food donations are down, and the organization’s federal commodity program has seen a 54% reduction in pounds of food received.

“We like to think the pandemic is behind us, but that’s not the case,” Solberg said. “We have a lot to prepare for this summer. So, as far as food security goes, our volunteers are needed to make an impact on us, and our community.” – Aryan Rai

Aryan Rai is a reporter for Food Bank News and a graduate student at Boston University.

CAPTION ABOVE: Volunteers at Second Harvest Heartland.