There has always been an undercurrent of anxiety among undocumented populations seeking food assistance. Food Bank News noted underground food distributions for the undocumented as far back as 2020, when the pandemic pushed the need for assistance to new heights.

Now that anxiety has been ratcheted up, as directives from the new administration begin to take hold. On its first full day in office, the administration decreed that immigration and customs officials would be able to carry out their enforcement activities in “so-called ‘sensitive’ areas,” including schools and churches – places that also often double as food distribution points for hunger relief agencies.

The hunger relief community is responding to the heightened anxiety as best it can – by educating immigrants about their rights, developing protocols for dealing with potential raids, training staff and volunteers, and at times emphasizing alternate distribution channels.

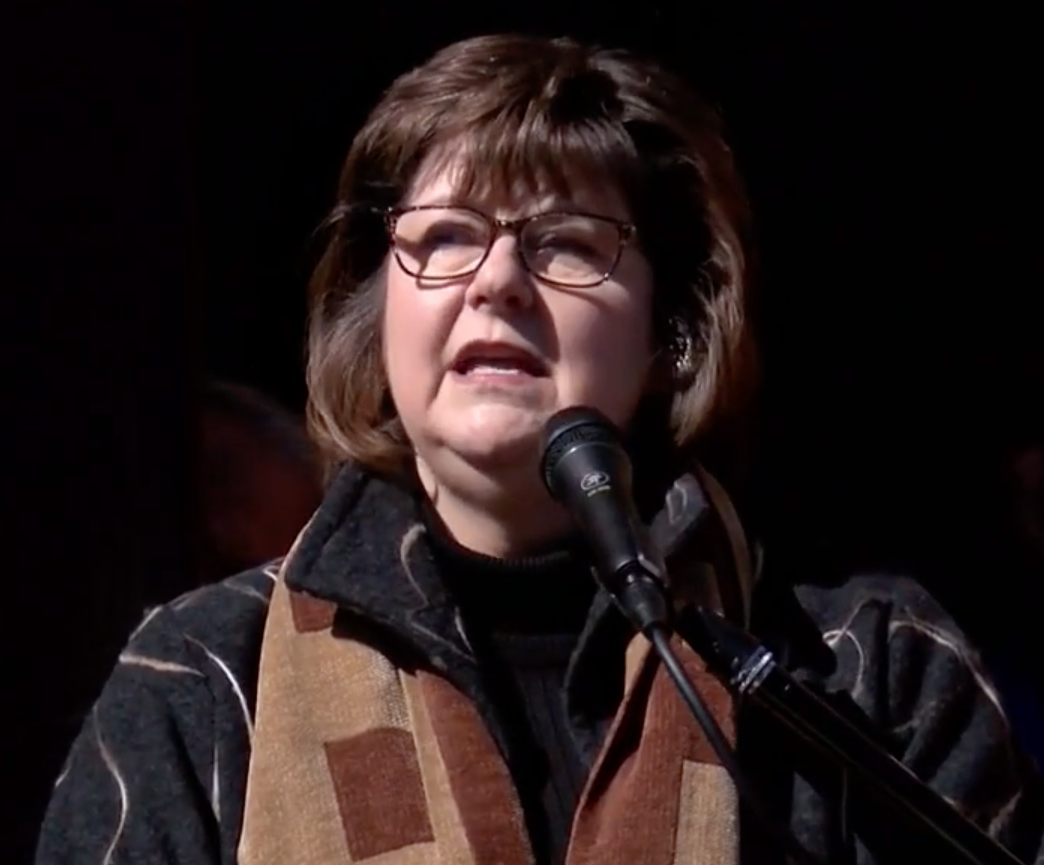

Mostly, they are seeking to convey an attitude of warmth and welcome. “A lot of people look to trusted organizations,” said Andrea Williams, President of Oregon Food Bank. “It’s our job as food banks, who a lot of people rely on and trust, to be that source of stability and credible facts and information. We don’t want to contribute to spreading fear.”

In Texas, two days after the administration’s directive was announced, El Pasoans Fighting Hunger held a press conference aimed at addressing the community’s concerns and conveying its mission of serving everyone. “We believe food is a human right,” said CEO Susan Goodell during the press conference. “And we are here firm every day making sure that our community gets the nutrition they need to stay healthy and strong.”

USDA guidelines do not require hunger relief agencies to collect information about immigration status or citizenship when providing food assistance. In fact, the USDA’s official requirements for TEFAP eligibility include name, number of people in the household, address, and a declaration of income. States, however, have wide latitude in how they interpret those requirements and many, for example, also ask for IDs, physical signatures, or other documentation. (See Capital Area Food Bank’s report, Strengthening TEFAP, for more on this.)

Even before the new administration took office, Ballard Food Bank in Seattle published a blog post reiterating its status as a safe place that serves all. It noted that it does not ask for proof of citizenship or residency, nor does it share information on guest identities or addresses.

In the post, Ballard clarified the protocol it would follow in case immigration officials showed up, noting that Ballard is a private organization with the right to ask people to leave. It said that federal agents with warrants (as they are required to have to enter private entities) would be asked to wait outside, so the food bank could call its attorney and a city representative to review the paperwork. “We’re all very committed to living our values of being welcoming and being here for our community,” said Jen Muzia, Executive Director. “We’re going to continue to uphold those values.”

CUMAC, a large hunger relief agency in Paterson, N.J., is pushing its version of “radical hospitality” with a just-opened welcoming space where people can take advantage of a coffee station and perhaps even get to know one another while waiting to use pantry services. Rather than have people wait outside, CUMAC is ensuring “when people walk through the door, they feel seen, they feel heard, they feel respected, they feel welcomed,” said Jessica Padilla Gonzalez, CEO. “With everything that’s happening in the world, we want to push that message even more. Like, you’re safe here. Talk to each other. We need each other more than ever.”

Anecdotally, food banks and pantries are reporting that attendance at food distributions by immigrant groups seems to be down, but few have yet to report relevant data. At the end of January, Pilsen Food Pantry in Chicago posted on social media that the pantry had been slower than usual. “Last week we attributed it to the cold weather, but this week, we are not seeing a lot of familiar faces,” it said.

Some pantries are emphasizing new distribution methods aimed at preserving client safety. Ballard is highlighting its reservation system, which lets people make appointments to get in and out of the pantry quickly. “We’re trying to find ways to minimize folks’ time as much as possible,” Muzia said. She added that home deliveries by trusted volunteers are highly valued, but require lots of manpower and take away from choice and community connection.

Pilsen Food Pantry is implementing a lottery system to reduce the outdoor crowds that occur when clients arrive one to four hours early before the pantry opens. The lottery will encourage clients to show up closer to the opening time of 10 am by handing out randomly selected next-in-line numbers at 9:30 am. “Waiting for long hours in long lines could be dangerous for many, and we hope this system benefits and protects the health of all our clients,” the pantry said.

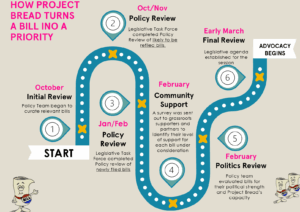

Some food banks are also responding to the new environment through advocacy, especially at the local level. Oregon Food Bank, for example, is moving full steam ahead on its effort to help pass a bill that would allow all people, particularly immigrants and refugees who are excluded from federal SNAP, to access SNAP-like services through a state program. On January 27, it gathered with other supporters at the state capitol to generate awareness of the bill, called Food for All Oregonians.

“We’re continuing work on what we already know to be true, which is that the Oregonians that experience the highest rates of hunger are Black, indigenous people of color, immigrants and refugees” and other groups being directly targeted by the administration, Williams said.

She noted that immigrants are not only fearful of going to food pantries, but also to grocery stores and local businesses. During the current administration’s first term, when enforcement fears also spiked, many businesses in a nearby community largely made up of people from Latin America were forced to shut down as people stayed home, Williams relayed.

“When you see communities withdrawing and sheltering in place, it’s going to impact the entire economy,” she said, noting that undocumented immigrants alone contribute about $350 million in taxes in Oregon. “I think we’re going to see pretty big ripple effects across the United States in terms of economic impact.”

For now, food banks and pantries are doing what they can to put out the welcome mat. “I think we’ll continue to be who we are,” said Muzia of Ballard Food Bank. “I think that’s the most important thing.” – Chris Costanzo

Photo, top: Supporters of the Food for All Oregonians bill, which would provide SNAP-like benefits to immigrants and refugees through a state program, gather outside the Oregon state capitol.

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News