When people think of Food is Medicine, they typically think of medically tailored meals and/or produce prescriptions. Those types of targeted solutions address patients with the most acute need for nutritious food.

But there’s a much bigger role that Food is Medicine should be playing, according to a report released last month by the Food Research and Action Center. Health care systems should be focusing the bulk of their Food is Medicine attention on getting people signed up for SNAP, the nation’s largest nutrition assistance program.

SNAP of course is deeply familiar to organizations working in the hunger relief space. Food banks play a big role in helping people get signed up for SNAP, a program that last fiscal year spent $112.8 billion to help an average of 42.1 million people a month purchase food.

Even though SNAP has many documented benefits, including an ability to improve health and well-being, it doesn’t spring to mind as a Food is Medicine intervention.

“There’s a real need to highlight the role of the federal nutrition programs in this space. We don’t want Food as Medicine to be synonymous with, ‘Oh, that means people are getting a medically tailored meal,’” said Alexandra Ashbrook, Director of WIC and Root Causes at FRAC.

SNAP already is featured as one of the foundations of the Food is Medicine pyramid (see figure, left). FRAC makes the case for SNAP’s importance much more forcefully, identifying it (along with WIC for moms, infants and children) as the primary intervention for Food is Medicine. “Ensuring eligible patients are participating in the federal nutrition programs — particularly SNAP and WIC — should be the primary intervention for health care systems to address food insecurity and improve patient nutrition and health,” said the report in its summary pages.

SNAP already is featured as one of the foundations of the Food is Medicine pyramid (see figure, left). FRAC makes the case for SNAP’s importance much more forcefully, identifying it (along with WIC for moms, infants and children) as the primary intervention for Food is Medicine. “Ensuring eligible patients are participating in the federal nutrition programs — particularly SNAP and WIC — should be the primary intervention for health care systems to address food insecurity and improve patient nutrition and health,” said the report in its summary pages.

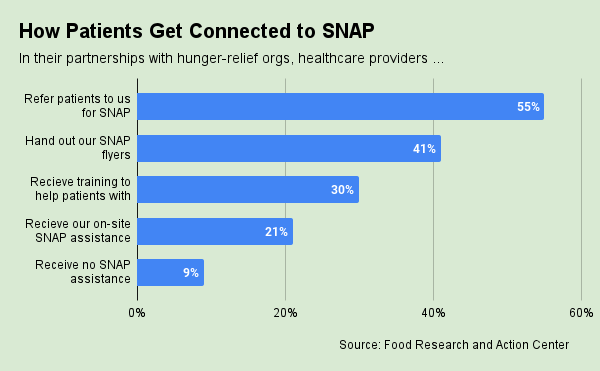

Putting SNAP at the center of Food is Medicine seems simple enough. But the wide variety of practices and technologies among healthcare providers complicates things.

“Each partnership develops differently,” said Sophia Lenarz-Coy, Executive Director of The Food Group, which is currently working with 25 healthcare locations to receive SNAP referrals. Anti-hunger groups need “quite a lot of adaptability,” she said, adding that each healthcare partnership raises very specific questions like: “What is their electronic medical record system? How much data do they need back? How frequently?”

The Food Group’s approach has been to embrace flexibility. “We will work with any health system that’s interested and that we can adapt to,” Lenarz-Coy said. Some providers may ask The Food Group to log into a system like Unite Us to access referrals. Others may submit printed reports from their electronic records system. The Food Group has even received faxes. “We’re trying to have our barriers to partnership be really low,” she said. “Because then we can bridge the healthcare world with the food world.”

Minneapolis-based The Food Group currently has three full-time staffers handling all the SNAP referrals that come in via the various healthcare platforms, as well as through its HelpLine call center. More than half of all the SNAP referrals The Food Group receives come from healthcare providers, Lenarz-Coy said. Food banks are generally well-suited to advance Food is Medicine through SNAP referrals, she said, because unlike pantries they have the administrative capacity to meet healthcare providers where they’re at.

Boston-based Project Bread has been refining its SNAP referral process with healthcare since it started working with providers about 15 years ago. Back then, it offered its hotline number and sometimes grocery store gift cards to patients who screened positive for food insecurity. The eventual emergence of the two-question Hunger Vital Signs screening tool led more providers to understand the depth of the food insecurity problem, which led to process improvements.

Now Project Bread is taking advantage of a system called Feed to Heal, which was developed by a primary care physician at Cambridge Health Alliance, one of Project Bread’s healthcare partners. Feed to Heal is “a very easy way for us to receive the referrals,” said Khara Shearrion, Senior Director of SNAP Outreach Programs at Project Bread.

The automated, secure system notifies Project Bread’s nine SNAP outreach workers of patients who need food assistance, while also letting healthcare providers follow up to see if the patient was successfully contacted, screened for SNAP eligibility, and signed up for the program. Over the past year, Project Bread has received more than 2,500 referrals through the Feed to Heal portal, Shearrion said.

Having an automated system that triggers outreach from Project Bread is far superior to supplying healthcare partners with hotline information to pass along to patients, Shearrion said. “Oftentimes when patients are in the health center, they’re already getting bombarded with so much information,” she said. “This is a way for us to lessen the burden on the patient’s end.”

Getting patients screened is a critical part of moving them toward food assistance (Food Bank News wrote about that here). That’s why Lowcountry Food Bank’s Food for Health program is focused on providing tools so its clinical partners can perform food insecurity screenings that are consistent, accurate, and dignified, said Nick Osborne, President and CEO. “We felt very strongly that it was critical to ensure that screening was done as an important first step, and it needed to be done clearly,” he said.

The South Carolina-based food bank determined that a big challenge in clinical settings is staff turnover. So it created two videos, each lasting a few minutes, to train healthcare staff on food insecurity screenings. The first covers the basics (even including the appropriate diagnosis code for food insecurity) and the second focuses on executing the screenings with dignity. Lowcountry plans to make the videos available to other nonprofit organizations to use for training. “It’s a resource for everyone to use,” Osborne said.

FRAC’s guideline to put SNAP at the center of Food is Medicine efforts makes sense to Annie Pham, Director of Social Health at Community Care Cooperative (C3), a Boston-based nonprofit that connects healthcare providers with community organizations to help solve health-related issues like food and housing insecurity. C3 has focused its efforts on solutions like medically tailored meals and produce prescriptions to meet the needs of patients with serious health issues.

“We quickly learned that we needed to do even more at the prevention level, to not only connect our members to the nutrition security programs like SNAP and WIC, but to think even bigger picture and support our members with economic stability so that we can have a longer and lasting impact,” said Pham, speaking during a recent webinar organized by the Food is Medicine Coalition and the Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation of Harvard Law School. “If we had more time and resources at the beginning, this definitely would have been something that we would have conquered sooner.” – Chris Costanzo

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News