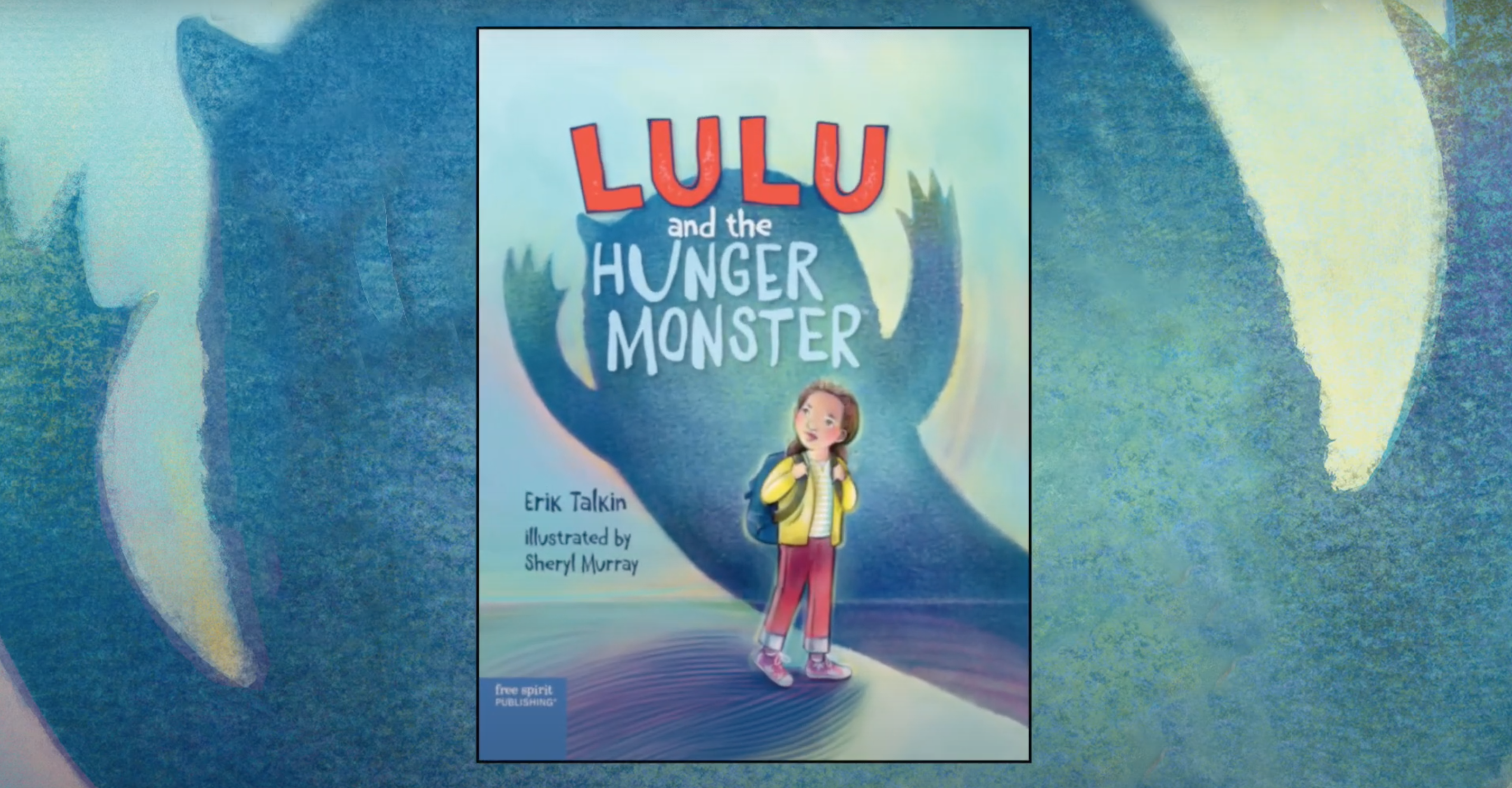

While Halloween has come and gone, and the specters of electoral politics wane, at least one monster remains. Or, that’s what Lulu and the Hunger Monster, a recently published children’s book by Foodbank of Santa Barbara County CEO Erik Talkin, would have you believe.

Lulu and the Hunger Monster is the story of Lulu, a joke-loving student who endures the challenges of hunger — personified in the book as a furry, blue, two-horned monster, invisible to everyone except the story’s protagonist.

“I began to think about what a child would want to read about in a book about hunger — this idea of this creature, that the person who is experiencing hunger can see, but that no one else can see — and what are the kinds of problems that that would bring up,” Talkin said. “I see that with kids especially, there’s a lot of stigma attached to being able to ask for help. Obviously, parents feel like that, but kids pick up on it, too. I wanted to explore a way of discussing hunger with kids that would be empowering for them rather than disempowering.”

Talkin is no stranger to the crisis of food insecurity: much of the book’s contents are rooted in observations from his vantage as a food bank CEO of how school-based food distribution programs in his community evoke shame and othering among students who receive food. “Witnessing that taking place at a couple of schools really made me want to explore the way in which our food bank could do things differently,” he said. Under his leadership, the Food Bank of Santa Barbara County has emphasized programming and partnerships that stray away from emergency food’s tendency to stigmatize and segregate participants, and has retooled the experience of the food bank so that those who enter the space feel respected.

Talkin is no stranger to writing, either — his work at the food bank is inflected by an impressive career as a filmmaker and writer with a master’s in writing children’s and young adult literature. “I’ve always used those skills at the food bank in terms of promoting and educating the work we do,” he said.

He hopes that the themes presented in the book spark change elsewhere, and is in talks with other food banks and schools who are interested in highlighting the book’s important issues with students, volunteers, and even donors. To that end, the book is accompanied by a Leader’s Guide, a resource with prompts and activities that offer intentional ways to destigmatize poverty among children and to develop community-based approaches to mitigating its worst effects.

While the injustices of hunger are of perennial concern, the pandemic has only exacerbated the timeliness and relevance of Lulu and the Hunger Monster. “COVID-19 has changed food banks dramatically around the country, including the ways they’ve had to change their approach to educational programming,” Talkin said. “I’m hoping that one positive result of the situation that we’re in will be a broader understanding among people about what it feels like to be food insecure.”

In the book, the monster’s near-constant presence in Lulu’s life calls the reader’s attention to the experience of food insecurity, and childhood hunger in particular, giving a textured picture that goes beyond merely the absence of food. While distinct, Lulu and the Hunger Monster echoes an advertising campaign out of the Atlanta Community Food Bank released last year that similarly used a monster figure to embody lesser-seen and under-discussed aspects of the experience of being hungry.

The impossible choices between spending on food and other necessary expenses, the pangs and pain and emotions that distract Lulu at school, and the ways experiencing hunger is stigmatized and silenced all loom large in Lulu’s life. “Monster made me promise never to say its name to anyone: HUNGER MONSTER,” Lulu narrates, disclosing to the reader a secret she’s otherwise keen to keep. With the help and trust of friends, her teacher, and her mom, Lulu endeavors to fend the monster off.

The book ends with a list of ideas for “standing up to the Hunger Monster” — practicing empathy, hosting a food drive, volunteering at a pantry, school gardening, supporting food banks — and Talkin centers the importance of taking action at multiple scales to address hunger, which is reiterated and expanded on in the Leader’s Guide. While the book tactfully does not go so far to say that we can simply empathize our way out of food insecurity, it could do more in terms of offering readers an entry point into advocacy and political consciousness.

Even so, Talkin recognizes how the book can instigate more of a conversation about how some in the U.S. have the ability to purchase food and others don’t. “It’s a question of getting young people to ask themselves, ‘Why is our country organized like this?’ in terms of there being this huge need for help,” Talkin said. “I think getting kids to think about broader issues like that is very positive.” — Austin Bryniarski

Austin Bryniarski is a writer based in New Haven.