The food bank CEOs of America have a lot to be proud of when they think back on the enormous amount of aid they’ve provided to vulnerable populations devastated by Covid-19. The Feeding America network alone (which does not include dozens of independent food banks) distributed more than six billion meals in 2020, up 44% from the year before.

Even so, the nation’s food bankers, including the CEOs who participated in our second annual CEO Roundtable Discussion, are aware of shortcomings in how aid is distributed. For one, stigma prevents many vulnerable people from accessing the food they need. Sometimes, the way food is distributed is not optimal. Then there is the familiar tension of tending to the immediate needs of food-insecure people, while the structural problems of poverty and racism that contribute to food insecurity in the first place persist.

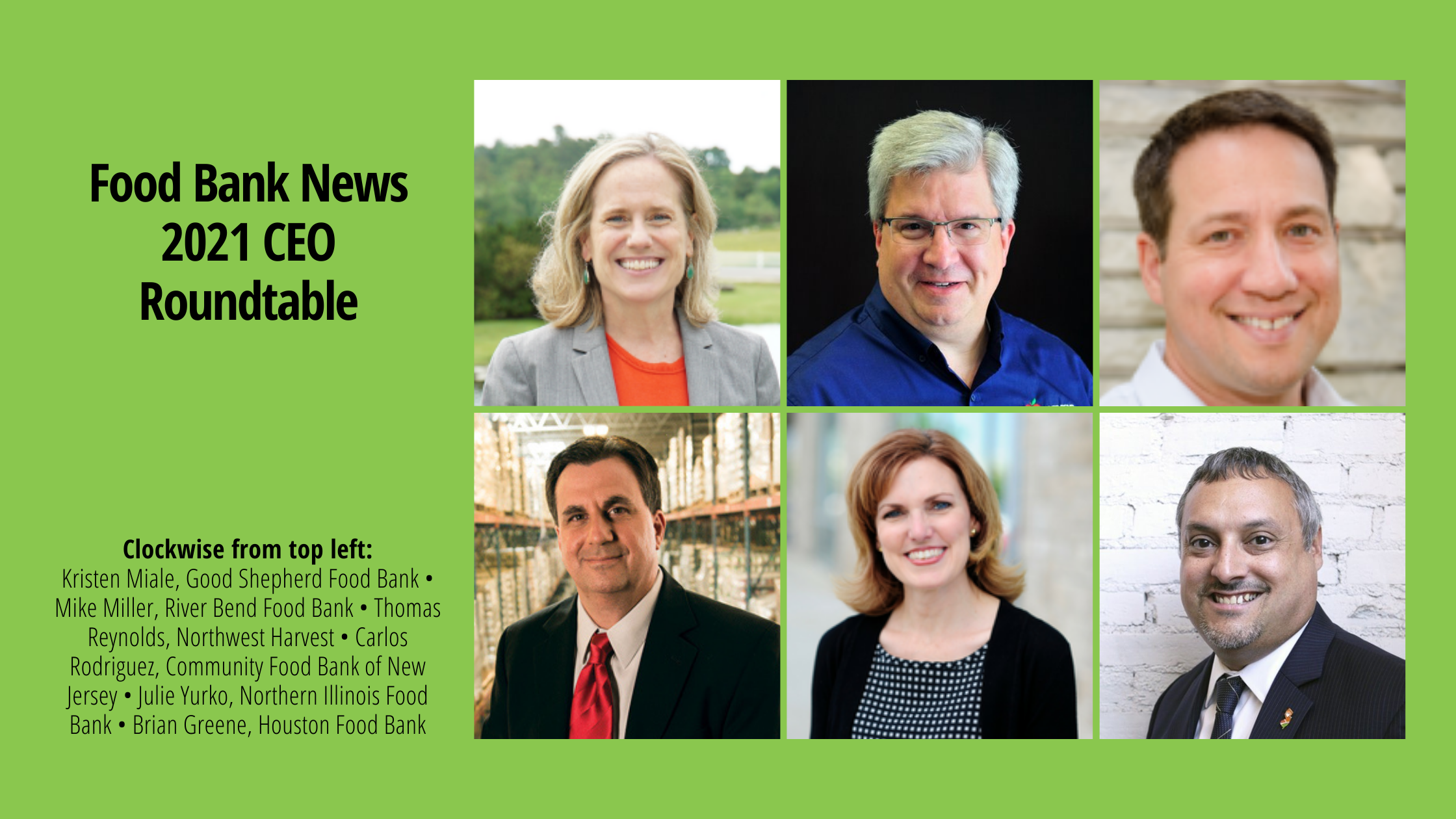

During our roundtable discussion, held online in November, CEOs expressed their concern about contributing to the idea that hunger can be solved by handing out meals. “We’ve helped build the narrative that hunger is something that individual good works can fix,” said Kristen Miale, President of Good Shepherd Food Bank of Maine. “Can it help? Absolutely … but this is all about a broken system.”

However, there’s nothing neat and easy about moving to a more progressive view of charitable food. While the concepts of a “right to food” and “food justice” have started to gain traction within hunger relief, those terms may be missing the mark, said Brian Greene, President and CEO at Houston Food Bank, because it’s not about food, it’s about income. “Even the term food justice pushes us in the wrong direction,” he said. “It’s economic justice. That’s what the conversation is.”

Then there are practical considerations that get in the way of working toward reforms. People need to eat, ideally three times a day, every day. At the same time, there is an enormous amount of waste built into our current food system, presenting a strong case for focusing on immediate needs. “The country throws away a third of the food we produce, so we might as well use the food,” said Michael Miller, President and CEO at River Bend Food Bank. “But we need to recognize that that alone is not going to fix the problem.”

Food banks should take care of the immediate need, while also nudging people into understanding the bigger systemic issues, said Carlos Rodriguez, President and CEO at Community Food Bank of New Jersey. “It’s tricky because you’re feeding the food beast while you’re trying to have the conversation about economic justice.” Food banks have a strong hand to play “because we have an audience and we have folks that are willing to listen,” he said. “That’s part of the value we need to put to work.”

Food banks should own and celebrate the fact that they are delivering billions of meals a year, said Julie Yurko, President and CEO at Northern Illinois Food Bank. “That’s awesome,” she said, “and we build on that” by making sure food is distributed equitably, in response to community needs, and with care and dignity.

Thomas Reynolds, CEO at Northwest Harvest, proposed a radically different approach to resolving hunger by putting forth the idea that grocery stores offer food for free. As Reynolds has previously described to Food Bank News, he envisions grocery stores making food freely available to those who need it, rather than giving away their excess to food banks. After years of calling grocery stores and suggesting this to them, he is hopeful that one chain is about to pilot the idea, he said.

“Maybe one of the biggest problems here in the United States is how well developed the food banking system is and that very close relationship to tax incentives that go to corporations,” Reynolds said. “All of these conspire together to make us very limited in our thinking about how to actually solve hunger. I think we need radically disruptive types of ideas to challenge the way the system works.”

In the near term, food banks have plenty of priorities that are keeping them busy. Yurko of Northern Illinois said she is most concerned about the high percentage of households that are food-insecure, yet do not take advantage of food pantries or soup kitchens. “The fact that there is so much stigma around asking for food assistance is something that keeps me up at night,” she said.

Northern Illinois is addressing this issue by making it easy for clients to access food assistance. The food bank has adopted an expansive view of client choice, allowing clients a range of access options, including shopping at the food bank’s own food pantry, even at late hours, attending drive-through events or requesting free delivery of groceries. The food bank has also pioneered an online ordering service that lets clients order the food they’d like and pick it up at a location of their choosing. At the roundtable, Yurko noted that the food bank is seeing 22% growth in new families coming for food.

Aside from stigma, there are quality improvements to address. A Washington study found that users of food banks and pantries in the state were not always pleased with their experiences, Reynolds of Northwest Harvest said. According to the study, 31% said going to the food bank or pantry took too long and only 23% said they were able to find the foods they needed. “How do we think more in terms of delighting our customers with their experience?” he asked.

On the point of whether food banks would exist in their current form for the long term, not everyone was in agreement. “I really do think food banking will be largely viewed as irrelevant in the next two decades or so,” Reynolds said. But Miller noted that the goal of Feeding America has long been to distribute 8.5 billion meals a year. “If we ever achieved that, I promise you we can’t go away,” Miller said. “Because if we go away, we’ll be short 8.5 billion meals. So let’s build something with enough capacity to deal with food that would otherwise go to waste and put it to good use.” — Chris Costanzo

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News