It’s the rare celebrity chef who is also a policy wonk, but that at least partly describes Michel Nischan, a three-time James Beard Award winning chef who’s as conversant as anyone in Congress on the nuances of the farm bill. Nischan is also a food activist and innovator who figured out how to leverage the massive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) within the farm bill to promote increased fruit and vegetable consumption through the company he founded, Wholesome Wave. Now Nischan is setting his sights on fostering even bigger change through Medicaid, the federal program that provides health insurance to low-income Americans.

Nischan’s flagship Wholesome Wave program makes produce more affordable by doubling SNAP benefits when they are spent on fruits and vegetables. A companion program empowers doctors to “prescribe” healthy food through vouchers patients can spend at the grocery store or farmer’s market. The two programs reached nearly one million people last year. But with about 40 million people on SNAP (and many more eligible but not signed up), Nischan wants to go way bigger than that. He envisions tapping into the behemoth federal Medicaid program to get there.

“We’re audacious enough to think we can actually influence health policy,” he said.

In his quest to make produce accessible and affordable to all, Nischan wants to go beyond grocers and farmers markets to involve health care providers and insurance companies. In the expanded ecosystem he envisions, many things are possible: fruit and vegetable purchases could get reimbursed through Medicaid. Or tax credits could go to employers who use incentives to prompt their low-wage employees to purchase produce. Wholesome Wave is already in exploratory conversations with several health insurers on various initiatives, such as making pre-loaded cash cards available to heavy users of medical care for fruit and vegetable purchases.

Leveraging Medicaid is a tall order, even for someone who’s already figured out how to steer a tiny portion of the $65 billion of SNAP money in the farm bill toward produce purchases. Nischan’s success in swaying farm-bill policy has hinged as much on the economic jolt local farmers get from increased produce sales as on improved public health. Being able to influence health policy, however, “is a whole other thing,” Nischan acknowledged.

Initiatives would need to show that peoples’ medical conditions are improving through increased access to produce, which is a high bar to meet. In Nischan’s favor is a recent study from Tufts University, which found that covering 30% of the cost of healthy food purchases through Medicare and Medicaid could cost-effectively prevent more than 3 million cases of cardiovascular disease.

Insurers are motivated, given the high costs of treating expensive diseases like diabetes and hypertension. With the cost of dialysis for a single patient reaching $100,000 annually, preventing disease in the first place is the best remedy for lowering costs. That $100,000 equals the cost of providing 250 people with two servings of disease-preventing produce every day for a year, Nischan said. Given those economics, it’s no wonder that Wholesome Wave sees “health insurers as great potential partners,” he said.

Nischan’s mission to expand access to healthy food has had many “aha” moments over the years, the first being his son’s diagnosis with Type 1 diabetes (the kind related to an immune system problem, rather than obesity or inactivity). With two of his five children suffering from the disease, the connection between food and health became both glaringly obvious and intensely personal for Nischan. His response — to open a restaurant that served only organic, local ingredients and eschewed all processed food — led to the disillusioning realization that his vision of healty eating could only be enjoyed by the affluent clientele of his New York City restaurant, which was housed in a W hotel. “I couldn’t live with it,” he said.

A concrete plan to expand access to fruits and vegetables began to take hold after Nischan met Gus Schumacher, a former Under Secretary of Agriculture (now deceased) after whom a portion of the current farm bill is named. Schumacher had started two small federal programs allowing WIC mothers and seniors to use coupons to buy produce at farmer’s markets, providing a blueprint for Wholesome Wave’s current programming.

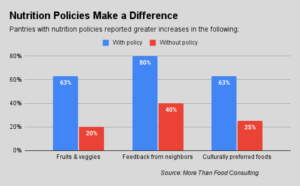

The Wholesome Wave model has since spread across the country, with organizations including the Fair Food Network in Michigan and Ecology Center in California now working to expand the reach of double-value produce coupons. Wholesome Wave’s programs alone reach 970,000 people in all 50 states at more than 1,400 locations, such as farmer’s markets and grocers. Nischan would love to see more food banks get involved in either distributing the double-coupon cards or taking the lead in setting up regional networks of farmer’s markets to accept them. “We see food banks as great distribution partners for incentive programs,” Nischan said.

While Nischan still misses certain aspects of working in restaurants, including the smells and the teamwork, the thrill of cultivating access to fruits and vegetables across the country eclipses those feelings. “With Wholesome Wave, I feel like I’m 30 years old again,” he said.