Many people working in hunger relief have likely heard the claim that solving hunger has nothing to do with food. But they may not go as far as Mariana Chilton in saying that it has everything to do with love.

Chilton’s assertion may be a tad unconventional, but she has plenty of credibility in this space. Her bona fides include founding the Center for Hunger Free Communities at Drexel University where she is a professor in the school of public health and where she launched a program called Witnesses to Hunger, perhaps the nation’s first effort to highlight the stories of people with lived experiences in the fight against hunger, as well as the Building Wealth and Health Network, a successful trauma-informed financial empowerment program.

Chilton’s view, based on decades of on-the-ground research, posits that hunger is often intertwined with a cascade of traumas, including generational poverty, violence, abuse and neglect. Years of talking with people living with hunger taught her that “food insecurity tends to be passed on generation to generation, and violence is the carrier,” she said in a virtual event featuring her recently released book, “The Painful Truth About Hunger in America.”

Her ongoing conversations with people ranging from members of Native American tribes to women in Philadelphia all led her to the same conclusion: “There’s no way that we can do this work without expanding our ability to love each other,” she said.

Love may be a lofty concept when it comes to hunger relief, but in practical terms Chilton is championing an approach that acknowledges a shared humanity. The people giving food and those receiving it should not be joined together in a power dynamic, but through solidarity, friendship and community.

That’s in line with principles increasingly being embraced by the hunger relief world, as it emphasizes dignity through such innovations as pantries that look and feel more like grocery stores, food distributions that are more equitable, and an emphasis on more trauma-informed care.

But Chilton deftly makes the point that a lot more could be done to incorporate dignity into charitable food. In her book, for example, she describes a flyer posted at a summer meals program in Colorado, which stated, “Adults MAY NOT eat off of a Child’s Plate!” She writes: “The flyer had a cartoon of people around a table, with three children at the table and two adults standing around. The adults each had a circle around their head with a red line drawn diagonally through it, as if to cross them out.”

She noted: “The deepest issue is that we’re not acknowledging each other’s humanity.”

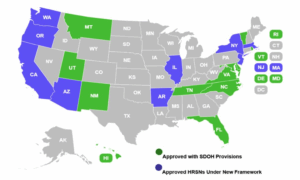

Chilton shared statistics that underscore there’s something deeper going on besides a lack of food when it comes to hunger. While the national rate of food insecurity generally hovers around 11%, the rates are far higher for certain groups, including indigenous communities, Black and Hispanic families, female-headed households, the disabled, and people who identify as LGBTQ. All of these groups experience discrimination. “Yes, we should be thinking about how to get people food and more money for food, but I’m insisting that we have to get underneath and start addressing racism and discrimination,” Chilton said.

Looking forward, Chilton contends that much more needs to be done to help hungry people than giving them financial empowerment and social support. Chilton is calling for “massive societal and political transformation,” including giving land back to indigenous communities, providing reparations to descendants of slavery, instituting universal programs for basic income, health care and preschool, and viewing food as a fundamental right.

In the current environment of harsh funding cuts, even contemplating this type of transformation seems far-fetched. But Chilton plunges ahead with information about various initiatives that have gained some traction, such as Real Rent Duwamish, which encourages people who live and work in Seattle to make “rent payments” (i.e. donations) to the Native American tribe that originally populated the city’s land.

She also discusses the U.S. Solidarity Economy Network, which emphasizes non-traditional economic models, such as cooperatives, community-supported agriculture and social investment funds. She asserts that the food sovereignty movement, which seeks to keep food systems under local control, is becoming more mainstream and cites the advances of organizations like La Via Campesina and the Detroit Black Community Food Sovereignty Network.

Chilton cautioned people against keeping their emotions in check when engaging in work related to hunger relief. “We have to be very careful not to let the focus on the intellect and on political solutions hijack our hearts,” she said. “It’s about keeping our hearts forward, keeping our sense of connection, and what it means to be human.” – Chris Costanzo

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News