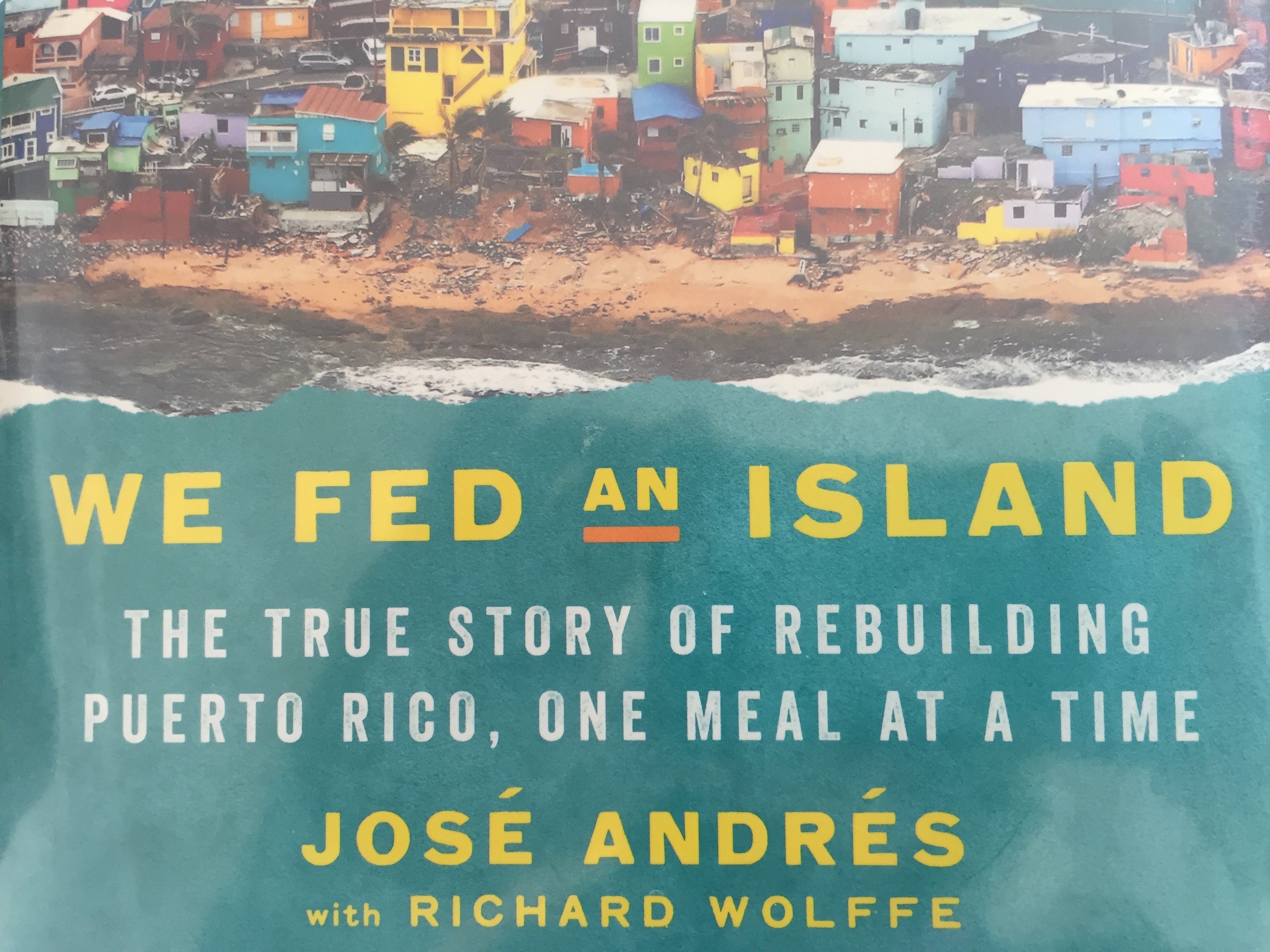

There is a running motif in Jose Andres’ illuminating book, We Fed an Island, in which Andres and his crew enter through the backdoor of the Puerto Rico Convention Center so they can take part in official meetings about restoring order after Hurricane Maria. Andres has no invitation nor security credentials, but being a wily chef, he knows there will be a back door propped open for the kitchen staff to grab a smoke or take out the trash, and he quickly finds it.

Andres’ agility in gaining entrance into the building is a metaphor for the larger circles he runs around FEMA and the other agencies charged with bringing relief to Puerto Rico. Andres, the award-winning owner of nearly 30 restaurants, has one goal — to feed the people — and no need for formalities, protocols, conventional thinking or permission in executing the task. He just bounds in.

The chef’s efforts go beyond heartwarming to border on heroic. In fact, his ongoing work in devastated areas through his World Central Kitchen non-profit, which exists to provide meals in disaster areas, has earned him a nomination for the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize. In Puerto Rico, Andres starts small, connecting with a food supplier and a fellow chef who lends his restaurant and gather s up other chefs. In his first full day on the island, Andres and his team knock out 500 sandwiches and two thousand hot meals. Within days, they are serving tens of thousands of meals, then hundreds of thousands, all while mobilizing funds and food trucks, expanding into bigger kitchens and getting the word out. Ultimately, Andres leads a months-long effort that brings more than 3 million meals to every part of the island.

s up other chefs. In his first full day on the island, Andres and his team knock out 500 sandwiches and two thousand hot meals. Within days, they are serving tens of thousands of meals, then hundreds of thousands, all while mobilizing funds and food trucks, expanding into bigger kitchens and getting the word out. Ultimately, Andres leads a months-long effort that brings more than 3 million meals to every part of the island.

Andres brings his big heart and a chef’s exactitude to the cause. He frets that his ham and cheese sandwiches, garnished with ketchup-flavored mayo, are drying out during transport, and orders them sent out in aluminum pans versus paper bags to preserve their moistness. “We don’t want to just give food,” he tells his volunteers. “We want to give the best food. And please put more mayo.” With his handmade sandwiches and big pots of sancocho stew, a local comfort food, Andres makes a mockery out of the soulless, plastic-wrapped Meals, Ready to Eat (MREs) being distributed by the government.

The book’s unvarnished look into the government’s ineptitude is as dispiriting as Andres’ efforts are uplifting. Andres sources his food locally, helping to revive the local economy, while FEMA signs a multi-million dollar contract (ultimately canceled) with a tiny U.S.-based outfit that plans to send over freeze-dried food. The agency puts up obstacles to signing a big contract with Andres, despite the fact that his operation is the only one producing food in large quantities. FEMA clings to its conventions and formal bidding processes, all the while maintaining a hostile attitude toward Andres, even to the point of escorting him under armed guard from the convention center (after he’s once again entered through the side door).

Through it all, there is Andres’ fortitude and clarity of purpose. The experience is not easy; he cries a lot. But the purity of his mission creates a form of simplicity. When he requires food beyond the capacity of his original supplier, he just goes to Sam’s Club. “I could never understand the other NGOs struggling with supplies when the answer was as easy as Sam’s Club,” he writes. Certain disaster-relief solutions — like utilizing the enormous kitchen capacity of sports stadiums and tapping into airline caterers — become glaringly obvious in his telling.

Most obvious is that a chef is what you want at the helm when disaster strikes — someone who leads from the heart, embraces complexity and creates order out of chaos. “We solved the problems as they popped up, as chefs do,” Andres says. “And we just started cooking.”

ABOVE: Volunteers at one of the massive sandwich-making lines in Puerto Rico.