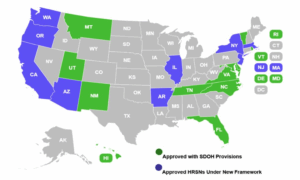

The timing could not have been better to demonstrate that major Food is Medicine interventions can improve patient health, while lowering costs.

Three research studies released in as many months all point to a variety of positive outcomes related to Food is Medicine initiatives. The studies out of North Carolina, Michigan and Massachusetts – released respectively this February, March and April – are a welcome development in the face of the potentially large cuts to Medicaid currently being debated by the federal government.

In North Carolina, researchers found that the state’s Healthy Opportunities Pilot, funded through a Medicaid 1115 waiver, resulted in lower Medicaid spending over time. While the costs of serving patients in the pilot were higher initially than those in a control group, the costs eventually started coming down by an average of $85 per beneficiary per month. Pilot participants also had fewer emergency room visits.

“The financial implications are more dramatic and more eye-opening than I had anticipated,” said Gideon Adams, Vice President of Community Health and Engagement at the Food Bank of Central and Eastern North Carolina. His food bank participated in the pilot by delivering produce boxes to hundreds of families in five counties in the southeastern part of the state (see our article on the food bank’s work with the pilot here). “Ultimately, it’s much, much cheaper to treat people in this fashion than in the traditional fashions.”

In Michigan, researchers zeroed in on the impact of a Food is Medicine program run by the Food Bank Council of Michigan, South Michigan Food Bank and Grace Health, a federally qualified health center. Patients deemed food insecure were given grocery boxes, consistent nutrition counseling, and recipe assistance.

Researchers followed these patients for nine months and found that their blood sugar levels and body mass indices both decreased, while food and vegetable consumption increased. Overall food insecurity among participants decreased dramatically, and patients ended the program with more consistent medication adherence and better overall health status.

Dr. Dawn Opel, Chief Innovation Officer and General Counsel of the Food Bank Council of Michigan and an author on the study, said the research highlighted the use of grocery boxes instead of full meals as an intervention. “The intervention hasn’t really been standardized yet, meaning if you’re writing a prescription, what are you writing a prescription for?” she said.

By implementing the program in a federally qualified health care setting, the study also shed light on ways for food banks and healthcare providers to best work together. “The food bank can learn more about what it really is that moves the needle when you work directly with patients in a healthcare setting,” she said. “We’re basically saying, federally qualified health centers are the right place to put these because we share a mission.”

In Massachusetts, researchers studied about 20,000 people who received nutrition services through the state’s Food is Medicine program, and compared their outcomes against those of about 2,000 people who were eligible for the program but did not participate. It found that program participants experienced a 13% reduction in emergency room visits and a 23% reduction in hospitalizations. While total cost of care between the two groups did not differ, the researchers found significant cost savings among a subgroup of individuals who were enrolled in the program for longer than 90 days.

Taken together, the studies give momentum to Food is Medicine at a time when a major source of funding for such initiatives is in peril. Will such interventions continue going forward? “That’s the $64,000 question,” Adams said.

His dream is to see a Food is Medicine program that intervenes proactively, instead of waiting for the population to get sick. He is hoping for adoption of Food is Medicine into Medicaid “writ large,” and even expansion into partnerships with private insurers seeking to lower their costs of healthcare.

Adams acknowledged that the federal funding climate is making people cautious. At the same time, the cost savings could be encouraging to people looking to streamline budgets. In general, Adams is trying not to get too caught up on the dollars. “We’ve got to keep the people at the center of this, and that’s why it is important to have these studies,” he said.

In Michigan, Opel is waiting to see what happens with “the looming Medicaid cuts,” but is not entirely pessimistic. Food is Medicine has more traction among medical and health stakeholders than she has seen in the past, and she does not see these programs going away. However, any pressure on funding any element of Medicaid “will have an effect on moving more preventatively,” she said.

“I feel like a lot of folks are holding hands to try to make this move forward,” Opel said. “So that is all to say that I am not losing hope, and I’m still going full steam on it because I think it’s the right thing to do.” – Shelbi Polk

Shelbi Polk is a freelance journalist and MFA student based in Durham, N.C., where she covers books and innovative social programs.

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News

This article was made possible by the readers who support Food Bank News, a national, editorially independent, nonprofit media organization. Food Bank News is not funded by any government agencies, nor is it part of a larger association or corporation. Your support helps ensure our continued solutions-oriented coverage of best practices in hunger relief. Thank you!