The Global FoodBanking Network may have less reach than the Feeding America network. But its members face challenges that have caused some to start to pull even with their U.S. counterparts along certain measures.

Data from 54 GFN members, most of which operate in emerging or developing countries, show that global food banks distributed the equivalent of 1.7 billion meals in 2023, an increase of 25% from a year earlier. That compares to 5.3 billion meals distributed by Feeding America’s 200+ food banks and affiliates.

Despite the current smaller impact, some GFN food banks are poised to scale up their volumes, thanks to their use of technology. They are also positioned to boost the already high percentage of nutritious food they provide. And they are well-equipped to track and quantify the impact of their work as it relates to climate change.

Technology similar to Feeding America’s MealConnect, which lets food donors such as restaurants and grocers contribute through an app, is expected to expand the impact of GFN food banks. The technology lets them build up donations and distributions without having to invest in heavy infrastructure like truck fleets and warehouses.

Working with providers like Ireland-based FoodCloud, GFN food banks are facilitating connections between food donors and nearby partner agencies that can pick up and distribute the donated food, without the food bank needing to get involved in transportation or storage.

In 2023, the volume of food going through such apps increased from 5% of total distribution in the GFN network to 11%. “That could easily grow to 30% within the next three years,” said Lisa Moon, President and Chief Executive Officer of Global FoodBanking Network.

She added, “We are really focused on these technology tools. We think it is potentially not just the best way to scale, but for many members, it’s going to be the only way to meaningfully scale with the kind of financial environment that we’re in.”

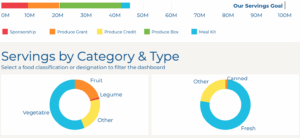

Global food banks also compare well with U.S. food banks when it comes to the nutritional content of the food they provide. Fresh produce is the largest single category of food distributed, making up 40% of the total. When other nutritious foods like grains, nuts and dairy are included, the percentage increases to almost 60%.

Food recovered from farms is fast becoming a major source of that fresh produce. Agricultural recovery increased by 35% last year, according to GFN, accounting for about 20% of the network’s total volume. “I would expect that to grow to 40% in the next three years,” Moon said.

In a departure from the focus of U.S. food banks, many in the GFN network are attuned to the impact of their work on carbon dioxide emissions. GFN estimates that its network has mitigated the equivalent of 1.8 metric tons of carbon dioxide – about the same as moving 400,000 cars from the road. (Feeding America does not appear to track an equivalent measure of carbon dioxide mitigation.)

Moon noted that many of the emerging and developing nations in which the GFN food banks operate are being very significantly impacted by climate change, putting more of an environmental lens on food banking’s benefits. Climate change is “not a political issue like it is in the U.S.,” she said. “They’re seeing firsthand the damage that it can do.”

In other metrics, the GFN network served 41 million people last year, up nearly 10 million from 2022. The network now includes 63 organizations in 54 countries, up from 54 organizations in 44 countries the year before. – Chris Costanzo

PHOTO, TOP: Lagos Food Bank Initiative in Nigeria recently started an agricultural recovery program. Here, volunteers and team members help to rescue sweet oranges from a farm about two hours north of Lagos.

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News