Food banks have long emphasized better nutrition in the food they distribute. Now, serious structural changes are making elevated nutritional quality a lasting characteristic of food banking.

The most important of these may be the development of nutrition guidelines specifically for use in the charitable food system. Introduced two years ago, the guidelines from Healthy Eating Research (HER) are increasingly permeating food banking, with Feeding America encouraging their adoption by all 200 of its food banks over the next three years.

Adoption of the guidelines got a big boost in the fall when a cohort of 32 food banks signed on to work with Partnership for a Healthier America to implement nutrition ranking systems in accordance with the HER guidelines. The new cohort more than doubles the number of food banks working with Partnership for a Healthier America on nutrition guidelines from 27 to 59.

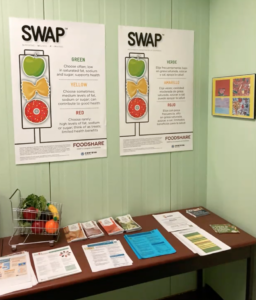

Another boost for the guidelines has come in the form of tools from Institute of Hunger Research & Solutions that help food banks and pantries do the work of actually implementing the guidelines – like classifying all food into nutritional categories and nudging clients to choose the healthier options. Created by Katie Martin, PhD, the Institute’s Executive Director, the tools – known as SWAP for Supporting Wellness at Pantries – are in use in at least 40 food banks in the Feeding America network.

At the same time that usage of the HER guidelines is expanding, there is an uptick in the number of food banks adopting formal nutrition policies. Among the food banks introducing such policies just in the first three months of 2022 were Gleaners Food Bank of Indiana, Connecticut Foodshare and Tarrant Area Food Bank of Texas. Only one-third of food banks had a formal nutrition policy in 2018, according to Mazon: A Jewish Response to Hunger.

All of this activity is happening against a backdrop of heightened emphasis on nutrition from the USDA, which released in mid-March a report outlining its commitment to nutrition security (in addition to food security). Calling nutrition security an “emerging concept,” the USDA noted its importance in fighting diet-related disease, which is a leading cause of illness in the U.S., accounting for more than 600,000 deaths each year, or more than 40,000 each month.

“I’ve seen first hand the direct correlation between nutrition and the top five chronic diseases that drive our health care costs,” said Julie Butner, who spent much of her career in the healthcare industry before becoming President and CEO of Texas-based Tarrant Area Food Bank two years ago. “We’re trying to do what we can here to have an impact.”

At Tarrant Area Food Bank, that means instituting a nutrition policy (it went into effect in January) and becoming an early adopter of SWAP. Tarrant Area announced in March that it was officially rolling out SWAP, about a year after it began piloting the system along with seven other Feeding America food banks.

SWAP uses an intuitive stoplight system to rank foods according to how often they should be eaten – green for often, yellow for sometimes, and red for rarely. Three pieces of data from a food’s nutrition facts label – sodium, saturated fat and sugar – determine a food’s ranking. So while one can of beans may be green, another similar-looking one may be yellow because of, say, its sodium content. Fresh produce is always green.

In addition to ranking their inventories based on nutrition, food banks are using SWAP to get their pantry partners to order healthier food and promote it to their clients. After only one month of SWAP, pantry clients have been found to select 11% more green food and 7% less red food, said Brittney Cavaliere, Program Coordinator at the Institute, in a recent webinar.

Using SWAP has been eye-opening for Tarrant Area Food Bank, Butner said. Before SWAP, the food bank had used a homegrown system for evaluating its inventory, which put its level of nutritious food at 92%. With SWAP, the level dropped to the mid-70s, an outcome that underscores the importance of having all food banks work from a common set of nutrition criteria based on the latest science.

At times, SWAP has put Tarrant Area Food Bank into difficult positions. With donations from the food industry down 12% and government grants for food purchasing going away, the food bank is having a hard time sourcing protein. Recently, it reluctantly decided to accept chicken legs (ranked red) because chicken breasts (ranked green) were not available.

The thought of ranking an entire warehouse full of inventory can seem like a daunting task, so food banks are taking a variety of approaches, often starting small. Gleaners Food Bank of Indiana started with SWAP by ranking the food in its on-site pantry, before tackling the food in its warehouse, said Sarah Wilson, RDN, Nutrition Manager, in the webinar.

Once it started ranking food at the warehouse level, it began by ranking TEFAP-provided food first, then purchased food, then donated food (which encompasses the widest variety). Though the food bank started small operationally, it thought big in terms of planning, getting initial input and buy-in from a broad swath of managers throughout the organization, Wilson said.

Mass.-based Worcester County Food Bank, which does not currently offer online ordering for its pantries, got started by setting up a display of the SWAP stoplight system for pantry managers to view as they went about getting their food at the warehouse. A survey of its network to see who was interested in SWAP led to a number of informational presentations, and now six pantries are implementing the system, with more to come. “They love to talk about it,” said David Reed, Agency Relations Coordinator, on the webinar. “Once we get some partner agencies using SWAP, they’re able to spread the word about its impact.”

Long term, having a standard set of nutritional guidelines can help improve the type of food coming into the charitable food system in the first place. With a nutrition policy backed up by the guidelines, food banks can have more constructive conversations with food donors about the best types of food to give. Looking even further upstream, the guidelines could be used by federal programs like TEFAP to rank their products, saving food banks the trouble, while also broadening the positive impact.

Between the HER guidelines, the SWAP system to help implement them, nutrition policies, and support from organizations like Partnership for a Healthier America, there is accelerated momentum behind more nutritious food banking. All of it puts Martin in a state of gratitude at the prospect of a national nutrition program for food banks. “It’s totally happening,” she remarked. “It’s completely totally happening!” – Chris Costanzo

CAPTION ABOVE: The SWAP system in use at Tarrant Area Food Bank’s on-site pantry tells clients which items to choose often.

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News