Capital Area Food Bank is far from the only food bank to have faced disruptions during the pandemic as its pantries and other partner agencies struggled to stay open. But it may be one of the few taking a highly analytical approach to restructuring its pantry network, post-pandemic.

[This article is provided by McKinsey & Co., a content collaborator of Food Bank News.]

An important backdrop to Capital Area’s systematic evaluation of its pantry network is its five-year strategic plan, initiated before the crisis, to expand its services beyond food to include access to healthcare, financial coaching, job skills and other support. Key to this “food+” strategy is to connect with community partners that have complementary offerings to help fulfill this mission.

“We don’t see ourselves as just acting in the food sector, but eradicating poverty, and we need to reach across sectors to do that,” said Radha Muthiah, CEO of Capital Area Food Bank, one of the 50 largest food banks in the U.S., with revenues of $73 million, according to the Food Bank News list of the top 100 food banks.

Officially kicked off in summer 2019, Capital Area’s food+ strategy was put on hold last March as the food bank pivoted to make up for the shuttering of a majority of its 450 network partners. In addition to distributing food directly, the food bank brought on temporary partners, including non-governmental organizations, faith-based groups, and local governments to meet demand that jumped by 50% — from 400,000 to 600,000 people during Covid.

With day-to-day operations now settling into a new normal, the food bank is recognizing an opportunity to accelerate its food+ work, in the hope of countering economic disparities in its service area, where the top 20% of the population is 29 times wealthier than the bottom 20%, and where there’s a 30-year difference in life expectancy within a ten-mile radius. Pushing its food+ work forward will require the food bank to understand how to maximize its existing resources and partnerships, and how to find new partners for its expanded mission.

From earlier surveys, the food bank knew its client base lacked access to transportation and would benefit from receiving multiple services in one place. It also wanted to help people get workforce training that could make them attractive job candidates at a time when Washington, DC, and surrounding counties were growing economically, with companies opening or moving to the area.

“Our strategy has been to help individuals so they can be part of the growth that’s happening instead of continuing to be sidelined and marginalized,” Muthiah said.

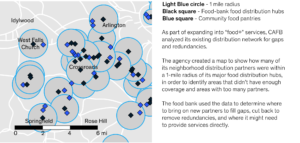

As it moves ahead with its food+ strategy, Capital Area is taking a deep analytical dive into its distribution network to identify both redundancies and opportunities for growth. Working with McKinsey, the food bank conducted a geospatial analysis to look for gaps in the existing distribution system, plotting the proximity of food pantry partners to major food distribution hubs.

It found that about 57 of the food bank’s direct distribution sites, or roughly 7% of the total, were in neighborhoods that were already sufficiently served by existing partners. This was an indication that the food bank would be better off redirecting resources to neighborhoods with unmet demand, either by bringing on new partners, or through direct distribution.

The analysis also revealed that 70% of Capital Area’s direct distributions were happening in a portion of its service area that was home to about 500 existing groups that could be potential food or food+ partners. As a next step, the food bank developed a set of criteria that it could use to identify the most promising food+ partner prospects in that group.

For the last piece of the puzzle, McKinsey helped Capital Area calculate how many partners the food bank would need to bring on, by area and services provided, to reach its goal of providing full food+ coverage by 2025. Specifically, it found that it will need to fill a gap of 72 distribution partners, including 14 in the area of K-12 education and eight in the area of health, to provide full food+ services throughout its coverage area within the next five years.

The data also showed that some groups it had brought on temporarily during the Covid crisis could make good long-term partners. In addition, as the food bank reactivates former partners that shut down at the beginning of the pandemic, it is using the analysis to determine which to prioritize adding back, based on where the need is greatest.

It is possible that some previous partners may not be interested or able to expand in ways that serve the community. As such situations arise, Capital Area will be able to ground conversations about partnerships in the data and put the needs of the food bank’s clients first, Muthiah said.

While Capital Area’s initiative is too new to draw conclusions about outcomes, it was important for the organization to “think holistically about its clients’ needs, and tackle the economic disparities that exist in the region now rather than wait for the pandemic to end,” Muthiah said. “If we aren’t careful about how we rebuild, the opportunity gap in our region will widen.” — Kyle Hutzler, Galo Tocagni, Pradeep Prabhala and Byron Ruby

Kyle Hutzler and Galo Tocagni are consultants in McKinsey’s Washington, DC, office, where Pradeep Prabhala is a partner. Byron Ruby is a consultant in the San Francisco office. Please visit McKinsey.com/FoodSecurity for more information.

Photo credit: Capital Area Food Bank

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News