The quest for funds is on, as food banks seek to aid millions of Americans stricken by economic fallout from the coronavirus.

With donated food slowing to a trickle, demand skyrocketing and the volunteer workforce dwindling, food banks are amping up their appeals to individual donors, while also exploring new methods of fundraising, all in an effort to generate way more funds than normal.

“We need money,” said Thomas Reynolds, CEO of Northwest Harvest in Seattle, the nation’s first epicenter of the pandemic. “We need a lot of money.”

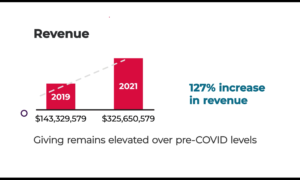

In fact, Feeding America says $1.4 billion is necessary over the next six months to support its network of 200 food banks (a calculation that does not include 50 independent food banks across the country, including Northwest Harvest).

In Texas, some money is being raised in the form of a novel partnership designed to address the twin challenge of lost jobs in the community and depleted volunteer workforces at local food banks. The effort pairs hunger relief agencies with a four-and-a-half-year-old staffing technology company called Shiftsmart, which has a platform that automatically schedules shifts for workers.

The partnership came about one Saturday toward the end of March when Anurag Jain, chair of the executive committee at North Texas Food Bank, saw Patrick Brandt, President of Shiftsmart. Both philanthropists, the duo thought they could create a solution that would address the food bank’s urgent need for volunteers, while also helping hospitality workers who were losing their jobs. “We wanted to get people who know food to help people who needed food,” Jain said.

Working with the Communities Foundation of Texas, the new entity, called Get Shift Done, has raised more than $3 million so far for wages to go to newly unemployed workers who sign up through Shiftsmart to pack, deliver, prepare or distribute food. Close to 1,200 people so far have been put to work since March 21, earning about $10 an hour and supplying about five million meals. Initially in 12 locations in the Dallas Fort Worth area, the shift workers are now active in about 30 locations around town, including food pantries, Meals on Wheels programs and schools.

The partners had never planned to make the platform available nationally, but have been fielding calls from interested cities and food banks all over the country since the start. Now Get Shift Done is also operating in El Paso, Texas, and is expected to soon be up and running in New Orleans, Arkansas, and Washington D.C. The intense pace is faster than any Jain has experienced, turning this period of social isolation into “a blur,” he said. “There has been so much interest and excitement.”

In Washington state, Food Lifeline, Northwest Harvest and Second Harvest are mounting a far-reaching effort that the three non-profits hope can scale up to meet the immense demand. Along with Washington governor Jay Inslee, the three food banks, which are the state’s largest, announced last week the launch of a statewide food fund that aims to amplify its impact by soliciting donations from state government, businesses, philanthropies and individuals in a coordinated way.

The WA Food Fund is focused specifically on procuring vast amounts of shelf-stable emergency food as well as cardboard boxes to put it in to meet demand from 1.6 million people, twice the normal amount who need food assistance in the state. The magnitude of the effort reflects the early window into the crisis that the leadership teams at the three food banks had, given that Washington was the site of the nation’s first coronavirus death.

“We were faced with this challenge very early on,” said Drew Meuer, Senior Vice President of Philanthropy at Spokane-based Second Harvest. “We saw the need climb faster than we could keep up with and recognized it would take a bigger response than any one of us could do on our own.”

The food banks are working with Philanthropy Northwest, which brings its trusted relationships with corporate and other funders, as well as help in managing and publicizing the fund. In addition to working together, the three food banks will continue to solicit food and fund donations on their own.

So far, the effort has raised more than $1 million of the $13 million total being sought to meet demand for food over the next six weeks, until government help in the form of SNAP and unemployment benefits starts to kick in. “In the interval between when families apply for and get funds, they are turning to food banks,” Meuer said. “Working together gives us the ability to combine our resources and acquire the volume of food we’re seeking to supply across the state.”

While Philanthropy Northwest has helped to coordinate other joint fundraising efforts, none have been as large as this, said Kiran Ahuja, CEO. Her organization plans to share the model with its peers in other states, she said.

Across the country, Greater Boston Food Bank is having success by sticking with its traditional methods of fundraising. “What we’ve experienced in the last five weeks or so is an enormous outpouring of support from people who just want in some way to help,” said Arlene Fortunato, Senior Vice President for Advancement at the food bank.

Greater Boston Food Bank is spending about $1 million a week to meet a 50% increase in demand for food, Fortunato said, and expects its Covid-19 related costs will rise to about $20 million through the end of December. So far, it has raised about $12 million of the $20 million extra it needs, mostly through unsolicited donations coming in to the food bank’s fundraising team of about 30 people, Fortunato said. “It’s so inspiring and moving to see how people are stepping up,” she said.

Every year, Greater Boston Food Bank raises about $19 million in philanthropy, so some of the current Covid-19 donors are accelerating contributions they would normally make at the end of the year, Fortunato said. The food bank also benefits from a $20 million line item in the state budget for food.

The food bank’s challenge is to think about how to continue to do fundraising once the urgency of the crisis has passed, Fortunato said. “In my experience, a very small percentage of new first-time big donors will convert to annual donors,” she noted.

In the meantime, Fortunato is absorbed with spending the new money quickly enough to meet the need, given constrained food supply chains. Only about 70 of the food bank’s 530 food pantries and other partners have closed because of the virus, and all of the remaining are experiencing increased demand. “We need to be sure we’re able to maintain our operations in this new normal,” Fortunato said. “That’s what’s keeping me up at night.”

CAPTION ABOVE: A food distribution from Feeding San Diego illustrates the massive need facing food banks as they seek to raise funds to meet it.