Compared to the general population, the number of college students who are food-insecure is shockingly high, a reality that is pushing food banks into new partnerships with college campuses.

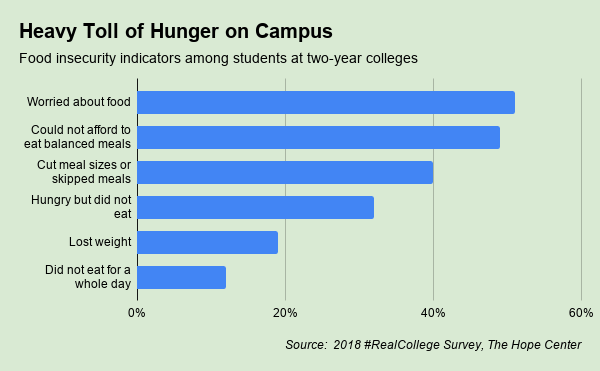

While 12% of U.S. households are food-insecure, a whopping 45% of college students surveyed reported being food-insecure in the nation’s largest and most recent assessment. That’s nearly half of students reporting some level of food insecurity, ranging from worrying about having enough food, to skipping meals, to going without food for entire days (see chart).

“The statistics are crazy,” acknowledged James Floros, President and CEO at San Diego Food Bank. “That old story about starving students — it’s not so cute anymore.”

Aside from the outright need, food banks are motivated to address college hunger for the potential it offers to address root causes. “We strongly believe education is a major vehicle to break the cycle of poverty,” Floros said. “So this goes right to the core of what we’re about.”

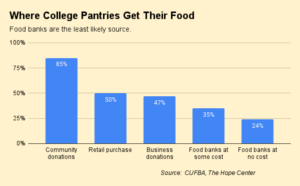

Signs of the college hunger problem began emerging a few years ago, and bloomed into fuller view when the Hope Center for College, Community and Justice began surveying college students about their basic needs. Now in its fourth year, the 2018 survey received responses from nearly 86,000 students in 24 states to support its finding that nearly half of college students were food-insecure in the prior 30 days. Also over this time, the College & University Food Bank Alliance, founded in 2012, has grown to include more than 700 campus food pantries as members.

San Diego Food Bank identified the problem of college hunger relatively early. When Floros began working at the food bank seven years ago, it already had a partnership with one college. Now it runs an official College Hunger-Relief Program that guides its work, which extends to every one of the dozen or so community colleges in its service area.

At Houston Food Bank, college hunger has emerged as a proving ground for the food bank’s Food Scholarship initiative, which seeks to use food as a catalyst to help individuals achieve their life goals. The food scholarships award participants 60 pounds of healthy food twice a month, as long as they maintain their eligibility by continuing their schooling.

In tying the food distributions to ongoing education, Houston Food Bank is setting itself a high bar for success, which goes beyond achieving food security. “Success is not food security,” explained Reginald Young, Senior Director of Strategic Partnerships at Houston Food Bank. “Success is when students graduate and now their earnings potential is increased.”

Given those lofty goals, Houston Food Bank’s partnerships with colleges involve much more than the typical discussions around food distribution. The food bank has had to establish data sharing agreements with the colleges and feedback loops with students to validate the intended outcomes of the program.

In the process, Houston Food Bank has moved well outside its comfort zone, becoming familiar with policies like FERPA (Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act), which protects the privacy of student education records, and college institutional review boards, which dictate the level of survey interaction that can occur with students. “We’ve had to learn a lot to do this,” Young said. “We’ve had to learn the language that the colleges use.”

Preliminary results are showing that students who take advantage of Houston Food Bank’s food scholarships tend to be more likely to complete their studies and have higher GPAs, Young said. The results of a fuller study examining the outcomes of the food scholarships are expected to be announced around the end of November.

As campus food pantries become more common, food banks and schools are becoming adept at integrating them more into college life. Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank, for example, intentionally refers to college distribution sites as “college cupboards,” not pantries. “It’s very important to us that it be like going to see an admissions counselor or an advisor, with no stigma attached,” said Charlese McKinney, Network Development Director at Greater Pittsburgh.

Similarly, Houston Food Bank has sought to integrate college culture into the pantries by tying in school mascots (to create the Gator Market at the University of Houston-Downtown, for example) and positioning pantries as resources where students can see cooking demonstrations or watch videos on nutrition education. In addition, all the pantries are run as client-choice, to mimic a regular grocery shopping experience as much as possible.

Communication at all levels is also key, Young of Houston Food Bank said. Widespread, high-level buy-in is important because college administrations can change. Food banks and colleges also need to work together to figure out the best way to reach students and recruit volunteers. At NC State University, for example, a podcast created by underprivileged students was a huge breakthrough in terms of breaking down the stigma associated with seeking help, said students from the school who spoke at the recent Closing the Hunger Gap conference.