Second Harvest Heartland of Minnesota announced last week that it would invest $13.2 million into smoothing out racial disparities in the way it distributes food, partly by making food more accessible and appealing to communities of color.

The commitment, which will roll out over five years, covers a wide breadth of activities, including sourcing culturally specific foods and providing support to businesses run by black, indigenous and people of color (BIPOC). The funding will also go toward improving access to federal benefits like SNAP, as well as research aimed at better understanding which communities need the most help.

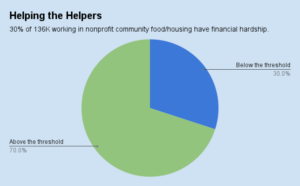

The multi-pronged initiative stems from a growing understanding of the deep racial inequities that exist throughout the country in the way charitable food is distributed. Despite the overall success of a massive effort to feed people during the pandemic, Feeding America has found that Blacks were 3.2 times more likely and Latinos 2.5 times more likely than whites to experience food insecurity in 2020.

Second Harvest Heartland also faces the particular need to lean into the challenge of operating in the community where George Floyd was murdered. “There is no better time to be bold than right now here in Minnesota,” said Allison O’Toole, CEO of Second Harvest Heartland, one of the nation’s largest food banks, with $237 million of revenues in 2020.

Even at a time when food banks across the nation are more focused than ever on addressing racial inequities, the size of Second Harvest Heartland’s investment stands out. A number of food banks, including Maine’s Good Shepherd Food Bank, are making significant grants to community organizations run by people of color. Similarly, Greater Chicago Food Depository has committed $5 million in grants to expand food access in high-priority Black and Latino neighborhoods and is planning more.

As a $13.2 million investment by a single food bank, Second Harvest Heartland’s effort is on par even with the Food Security Equity Impact Fund started in March by the much-larger Feeding America, with a $20 million seed donation. Claire Babineaux-Fontenot, Feeding America’s CEO, praised Second Harvest Heartland’s commitment at the event where it was announced. “I applaud you,” she said.

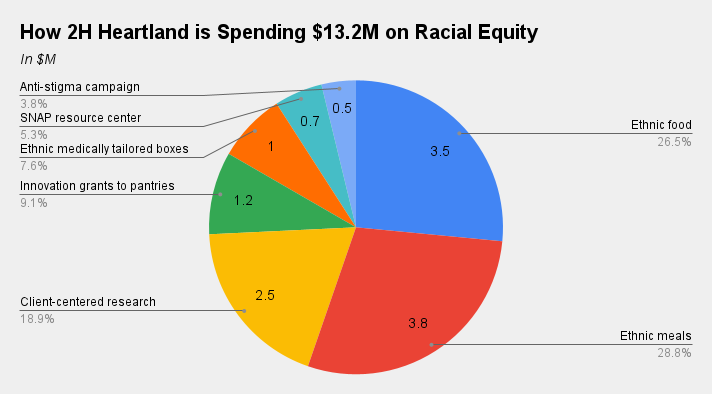

Of the $13.2 million, Second Harvest Heartland will allocate $3.5 million to partnerships with communities of color to source more culturally connected food. That includes about $1 million that will go toward a contract with a local nonprofit that will collaborate with 25 BIPOC farmers to source fresh produce, including products like sweet-potato leaves and African eggplants.

Another $3.8 million will go toward sourcing and making culturally connected prepared meals that will be distributed through Minnesota Central Kitchen, a Second Harvest Heartland initiative that emerged as a response to Covid-19, and now has become a permanent program. MCK, which is on track to soon distribute its two-millionth meal, mobilizes underutilized restaurants to prepare quality meals for food-insecure people.

Working through MCK, Second Harvest Heartland will source and prepare meals all within three miles of where it distributes them, which will lead it to working with smaller kitchens that prepare more ethnically diverse meals. One example is an outfit called Afro Deli, which prepares halal meals for delivery to Somali elders who live in a nearby high-rise.

Second Harvest Heartland will also allocate $2.5 million to client-centered research to better understand food insecurity within specific communities. Another $1.2 million will go to food pantries that are undertaking innovative approaches, while $1 million will go to making the food bank’s FOODRx program, which distributes medically tailored food boxes, more culturally sensitive.

The final plank of Second Harvest Heartland’s program is aimed at buoying access to federal benefits. It will invest $700,000 in a resource center that will help the food bank aid the huge volume of people calling in to get SNAP assistance (up 53% compared to before the pandemic). And it will put $500,000 into an anti-stigma campaign aimed at reducing the shame around asking for help.

O’Toole noted that SNAP has nine times the power of the national food bank network. Given Second Harvest Heartland’s ultimate mission to “End Hunger Together,” the food bank’s overall effort “would not be complete without an investment in that programmatic work so we can reach more people who don’t have access to benefits,” O’Toole said.

Greater attention to racial equity is occurring at all levels of hunger relief. The USDA, for example, announced this week that it would establish an Equity Commission to address historical discrimination and disparities in the agricultural sector.

Feeding America’s Food Security Equity Impact Fund is also a significant development. Babineaux-Fontenot said one rule related to the fund is that only communities of color get to decide what to do with it.

“Way too often national organizations think we know the answers and we spend the money on us — our training, our development, our thinking,” Babineaux-Fontenot said. “Breakthroughs in this space happen if and only if we go into communities in partnership, without paternalism, without condescension, and provide resources that become the resources of the community.” — Chris Costanzo

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News