Early on in the pandemic, NYC-based Met Council, the nation’s largest kosher food pantry network, was invited to a meeting at the mayor’s office where government officials ran down a list of more than 800 food pantries to make sure each had access to the city’s emergency food system.

When just a few dozen were left on the list, Met Council noticed a theme. Many of them were organizations associated with the Muslim community. Muslims comprise about 9% of the city’s total population of about 8.6 million, according to the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding.

“They did not have a natural partner at that table,” said Jessica Chait, Managing Director of Food Programs at Met Council, which last year distributed 20 million pounds of food a month to more than 200,000 New Yorkers. “We know what it means to be left out of food programs and policies. We raised our hands and said, ‘We will make sure that these organizations are supported.’”

Thus it came to be that the Jewish organization began providing food and technical assistance to help Muslim groups connect to the emergency food system. The move is in keeping with Met Council’s mission to serve all New Yorkers in need regardless of race, ethnicity or religion, while also working to meet the specific requirements of those with religiously informed diets.

Taking into account religious diets is crucial to meeting the needs of all New York City residents. An analysis of 311 calls made to the city’s GetFoodNYC Emergency Food system during the height of the pandemic found that almost 21% of all participants requested kosher or halal food. (Halal refers to food that is permitted under Islamic law.)

Such requests are not simple preferences, but actual requirements that impact food intake. “We know far and away that people would rather not eat than to break with their religiously informed diets,” Chait noted. Given this imperative, Met Council has been advocating at the local and national level to help food banks and pantries better serve people who prefer a kosher or halal diet.

A first step has been understanding the scope of the issue. Knowing that 21% of 311 calls during the pandemic requested kosher or halal food was eye-opening. “For the first time, we had demand-driven data: This is New Yorkers telling us what they need,” Chait said. “Much of what we see in all of our food banking work is how much food we distributed, and then we say that many people needed food. But we don’t count the number of people we turned away.”

In an equitable world, Chait said, the finding that 21% of New Yorkers need kosher or halal food should dictate that 21% of food assistance dollars should go to agencies that can deliver that product. As Met Council seeks to get to equity, it is addressing two of the main challenges of meeting the needs of religiously informed diets: education and access.

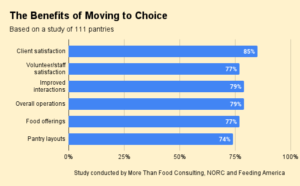

Pantries should know, for example, that religious communities are relatively easy to serve, Chait said. The most important aspect is to offer client choice, given that what’s kosher or halal to one person may not be so for another. Certain food categories, such as fresh produce, automatically qualify as both kosher and halal, she pointed out.

Another common misconception is that kosher or halal food is always more expensive. Chait acknowledged that the extra steps required to certify meat as kosher or halal might make it pricier than other meat. But an analysis of food prices in New York found that many kosher items, such as canned corn, were less expensive than their standard counterparts. “At the most basic level, it does not need to cost the city or the U.S. government more to access canned corn that is certified kosher than not,” she said.

Another challenge is that many food banks and pantries are uninformed about how to label or store kosher and halal products. Many are nervous that they will have to review ingredient lists, when in fact kosher products are usually labeled as such.

One food bank told Met Council it couldn’t store kosher food because it would have to keep it separate from non-kosher goods. That’s only true for some items, such as meat, Chait said. “By and large, it’s not an issue. This food bank simply wasn’t aware,” she said. “They had forfeited their responsibility, thinking they just couldn’t possibly maintain storage for this.”

A systemic lack of awareness about how to label or store kosher and halal goods underscores the need for education. To that end, Met Council is training food pantries and banks and convening stakeholders around the country to help expand access. Sizable communities of Jews and Muslims exist in states including Michigan, Florida, California, Arizona and Texas.

The organization recently participated in a listening session in connection with the White House Conference on Nutrition and Hunger and has advised the USDA on how it can expand its offerings of halal and kosher friendly foods through The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP).

In 2020, only two products on the TEFAP list were required to be kosher, and one halal, making it difficult for pantries that rely on TEFAP to source those types of items. “This just creates a tremendous issue for programs across the country to have what they need to be able to serve their clients balanced pantry bags,” Chait said. “You have groups shying away entirely, saying they don’t have enough flexible funding to supplement pantry bags and fulfill the mandate for a balanced bag.”

By January, Met Council’s advocacy efforts are expected to expand the TEFAP list to include eight kosher items. Chait says it’s a positive step, albeit a slow one, noting that changing the massive government program is like “trying to turn an ocean liner.” It has also advocated for legislation that would require TEFAP to collaborate with Jewish and Muslim community leaders to develop training materials around the storage, transportation and distribution of kosher and halal products in the program.

Met Council has also been working at the local level for greater kosher and halal food access. For its own organization it recently hired a halal pantry coordinator who grew up keeping a halal diet.

As Met Council works with the groups in the Muslim community, staff are clear that the goal is to offer assistance and lift their voices, not take over programs. Designing programs in partnership with communities makes it easier to meet needs and recognize ways to improve impact, Chait noted. “We believe that the case for more equity in the food system is enhanced when we talk about various communities who not only have similar and shared traditions, but challenges in access,” she said.

Chait is hopeful that the time is right for change. “I really do believe that — whether it’s this administration or just simply that this moment has people really committed to understanding how they can create a more equitable program,” she said. – Ambreen Ali

Ambreen Ali writes the monthly Pantry Link column for Food Bank News. She is a widely published journalist and founding editor of Central Desi, a newsletter about New Jersey’s South Asian community.

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News

This article was made possible by the readers who support Food Bank News, a national, editorially independent, nonprofit media organization. Food Bank News is not funded by any government agencies, nor is it part of a larger association or corporation. Your support helps ensure our continued solutions-oriented coverage of best practices in hunger relief. Thank you!

Connect with Us: