When it comes to targeting hunger, Maine’s Good Shepherd Food Bank has found a hyper-local approach can be hyper-effective.

The food bank recently announced a $100,000 investment to close the meal gap in one of the state’s larger counties by putting those who live in the county in charge of deciding how to use the funding. The effort is part of an ongoing initiative, started in 2018, to implement local, community-driven solutions to food insecurity in each of 27 regions identified by the food bank.

The approach is a departure from the top-down approach many food banks tend to take in funding community projects. Like many of its peers, Good Shepherd traditionally relied on an internal team to develop strategies and make funding decisions on behalf of communities. While the process was efficient, “it failed to honor the community members’ and leaders’ wisdom and ingenuity,” said Shannon Coffin, Vice President of Community Partnerships.

Under its community-driven strategies approach, Good Shepherd acts as a convener and neutral facilitator, allowing communities to decide how to use Good Shepherd’s funding to close their meal gaps. “We are playing our best role when [Good Shepherd] invests in and supports communities’ visions of what access to the right food at the correct times and places means for them,” Coffin said.

Good Shepherd typically begins its community-driven process by compiling essential data about each region and working with local organizations to identify community stakeholders to join the cohort. It then supports those stakeholders in completing a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis of the region’s ability to close its meal gap. Stakeholders then develop project plans, design the funding process, review applications, and make funding decisions.

With local stakeholders driving the process, the outcomes are community specific. In one county, for example, stakeholders invested in four food-access solutions sponsored by separate organizations, while in another, stakeholders funded a shared “community connector” position.

So far, Good Shepherd has completed three cohorts, begun a fourth, and expects to execute the process in each of the 27 regions by the end of fiscal year 2028. After committing $35,000 in its first cohort, it soon realized that big impacts required deeper funding. So it increased its initial funding and has funded $100,000 in each subsequent one.

As with any novel approach, there have been challenges. In the first cohort, for example, Good Shepherd found that its active leadership in organizing meetings led cohort members to defer to the food bank. Good Shepherd now provides stipends to community-based organizations to organize the effort, limiting its role to administrative support, neutral facilitation, and funding.

Success with the approach has led Good Shepherd to bring local stakeholders into review committees for other programs as well. “Incorporating community stakeholders builds trust with applicants and helps us ensure that we’re achieving maximum impact with the dollars we have to invest,” Coffin said.

While Covid has made it harder to measure immediate results, Good Shepherd is taking the long view. “We hope that by bringing people together, modeling the values of power sharing, and centering those most impacted as experts in their own lives, as well as investing meaningful amounts in communities’ dreams for themselves, we can play some small part in setting the stage for those revolutions,” Coffin said.

Coffin noted that a community-driven approach takes some adjustment. Everything takes a bit longer, and mistakes happen, she said, but it’s part of the process. “When we’re transparent about the mistakes made and willing to engage in an honest dialogue about lessons learned, it supercharges trust instead.” – Amanda Jaffe

Amanda Jaffe is a writer and former attorney with a deep interest in the organizations and mechanisms that address food insecurity. Her writing has appeared in The American Interest, PASSAGE Magazine, and the Finder, among other publications.

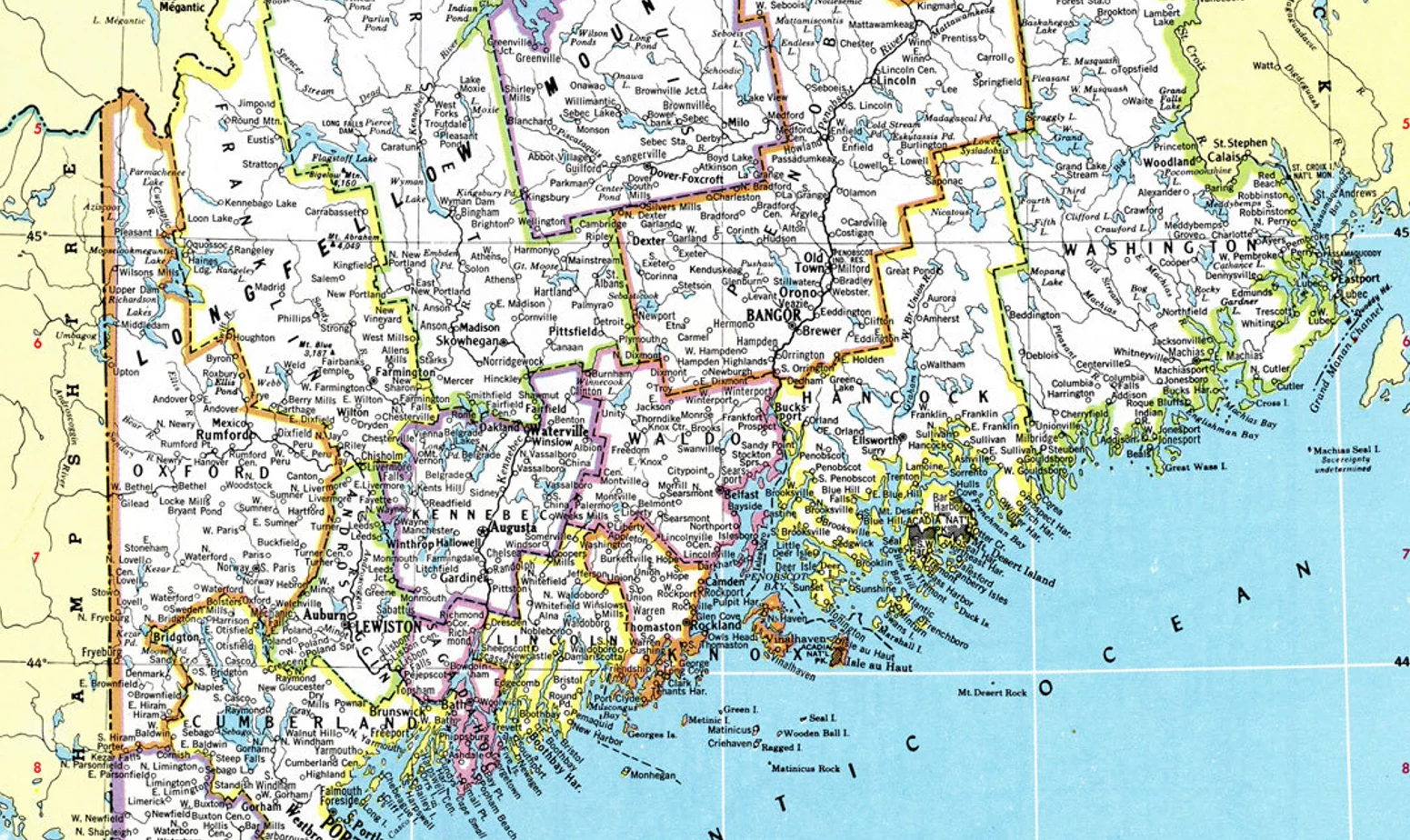

PHOTO, TOP: Some of the towns and counties of coastal Maine.

Like what you’re reading?

Support Food Bank News

This article was made possible by the readers who support Food Bank News, a national, editorially independent, nonprofit media organization. Food Bank News is not funded by any government agencies, nor is it part of a larger association or corporation. Your support helps ensure our continued solutions-oriented coverage of best practices in hunger relief. Thank you!

Connect with Us: